What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

June 1996

It's a good day for sailing, at Center Harbor in Brooklin, Maine. The sky is clear and the temperature has risen through the fifties, and there's just enough of a breeze, gentle on the land and slightly stiff over the water. At Brooklin Boat Yard it's a launching day, and among those gathered at the yard -- the boatbuilders, those coming to watch the launch, those here to sail the new boats -- there are many shades of anticipation, concern, and excitement. Launching days are big events, after all, a time when the work of the year is revealed and the dreams of the owners hopefully come true.

Two boats are sitting in the yard, up on jackstands, one behind the other. They seem suspended in motion, like stilled thoughts, some element of gravity missing just now (water) and some aspect of time (forward movement). The boatbuilders hurry about, climbing up and down ladders, moving to and from the shop, rigging lines and bending on sails, thirty feet from the dock. There's a huge mechanical contraption standing nearby, the Travellift, soon to pick the boats up in slings and set them into the water, once the high tide has come.

The boats are of a new design called the Center Harbor 31. They are beautiful to look at. The curved lines that run along the surface and toward the bow are instinctively pleasing, comfortable to rest the eye upon. At the bows of both boats are wreathsdressed in ribbons and flowers, wearing lustrous white, with the lovely lines, these two Center Harbor 31s, calledGraceandLinda,could seem like two beautiful schoolgirls off to the prom.

They are the product of the design work of Joel White, who began his career as a boatbuilder forty years before, constructing wooden lobster boats with an older boatbuilder. He bought the yard, built many more boats, and as of late has been creating a style of design that has become his own, one that he's become famous for -- boats simple of line yet sound in engineering, traditional above water and modern below.

Steve White, Joel's son, runs the yard now, and through the morning organizes the work onGraceandLinda.He also spends some time rigging, the work he enjoys most. Suspended on a bosun's chair from a hoist on the Travel-lift, he goes about attaching the roller furling jib unit to the mast. Nearby is Bob Stephens, project foreman for the two boats, helping to get the sails on.

The owner ofGrace,whose name is Frank Henry, was by early this morning to check on the progress. He and his wife have a summer home in Brooklin. Frank Henry had come up to the yard from New Hampshire several times over the winter to see the progress of the construction and to talk to the boatbuilders -- he'd been surprised that the crew had been willing to take time out to talk to him, even though the pressure was on to finish by the launch date. In the fall when they were still in the planning stages, Henry had been in Brooklin to confer with Joel White on the design. He had builtGracein fact, in order to have the experience of participating in the development of a new boat.Graceis the result of that effort and for Frank Henry this is a satisfying day. His children and grandchildren will be at the launching, and his wife, Grace Henry.

Previously the Henrys had owned a 42-foot racing yawl, with eight berths, a charcoal stove, and a supply of hot water. They had raced to Bermuda, cruised the Great Lakes, and sailed to New Brunswick, and the boat was the vehicle of many family memories, but after the Henrys' children grew up and got their own families and boats, the 42-foot racing yawl seemed much too big. One afternoon when they were sailing in Eggemoggin Reach the Henrys came upon a red-colored daysailer with beautiful lines-Joel White's personal boat,Ellisha,a fiberglass model called the Bridges Point 24 that Joel designed for a local boatbuilder. When Grace Henry sawEllishashe said, "Now that's more like it."

Frank Henry sailed a Bridges Point 24, and he considered buying one. But Henry wanted something more in a boat, and he wanted an experience in designing it. After talking with Joel White he looked through books about boats and yachting. InSensible Cruising Designs,by L. Francis Herreshoff, he came across a 29' 6" daysailer calledQuiet Tune,one of Herreshoff's "lifestyle boats," based on a simple approach to sailing.Quiet Tune,built in Maine in 1945, was designed for short cruises for two people. It was set up with a ketch rig-with two masts, a mainmast ahead of the cabin and a smaller mizzen mast stepped just forward of the tiller.Quiet Tuneappealed to Frank Henry. He liked the simplicity of the boat, and its size, and he liked the ketch rig because of the many sail combinations. They would allow him to make a lot of adjustments, to pull a lot of strings, as it's said, yet the boat would also be small enough for him to sail alone.

Joel White drew a preliminary sail plan based on the lines ofQuiet Tune.He tried to convince Frank Henry to build the boat as a sloop, but Henry wanted a ketch rig, and so Joel eventually devised a way of incorporating a mizzen and its rigging without too much awkwardness. Henry liked the looks of the sail plan and lines drawing, so they moved on to more detailed ones. They faxed comments and ideas to each other. As the two interacted, a new boat grew out ofQuiet Tune,and eventually the names on the drawings changed to the Center Harbor 31 andGrace.Henry, who had studied engineering in college before going to law school, enjoyed both the technical exchanges and the creative part of the process, the dreaming up of a boat that met both his and his wife's needs.

But before he signed a construction contract he made a condition that the yard must find a second client, since building two boats would substantially cut the costs. That second client was Alan Stern. He had arrived in Brooklin the night before with his son, Brian. They'd just come from Brian's college graduation, and planned to sail their boat back to Connecticut. Stern had built several boats, sailing them primarily on Long Island Sound. When he called Joel in the fall and heard about the Center Harbor 31 project, he soon signed on. But Stern didn't want a ketch rig. He wanted a sloop, with its bigger mainsail, so as to better utilize the light airs of Long Island Sound. Stern also wanted an enclosed head and a self-balling cockpit, and he wanted to be able to fly a big spinnaker. So Joel drew a boat with a deeper ballast keel, and slightly more freeboard, and a bow with more forward overhang. Stern named itLinda,after his wife.

Stern was pleased with the looks ofLinda.He liked the big cockpit with the eight-foot seats of sculpted teak, and he liked the way that the above-water appearance of a boat of forty to fifty years ago matched with the modern below-water appearance. Stern felt that withLinda,he had contributed to the development of the Center Harbor 31 in its sloop version.

The people from the General Store arrive at the yard, and set up a buffet table. Others come from the town. There's Doug Hylan, who runs a boatyard down the road, Benjamin River Marine, and who used to work for Joel White. There's Maynard Bray, who has also worked here, over the years, who is an old friend of Joel's, and who like Joel has written technical pieces and reviews of boat designs forWoodenBoatmagazine. And Jon Wilson, the founding editor ofWoodenBoat.There are the families of the boatbuilders. The cars are parked in the lot by the shop, and along the road up the hill from the harbor.

Amid the preparations and the gathering of the crowd, Joel White arrives. He's walking with crutches, and his wife, Allene, is with him. This is Joel's first time at the yard since undergoing an operation to have a section of his lung removed in Boston a few weeks ago. He's been dealing with lung cancer for the past six months, and he's been using crutches since undergoing a bone graft in his leg, also the result of cancer. He's bald from chemotherapy, wearing a visor cap, and moving gingerly, but Joel is cheerful. There's warmth and curiosity in his eyes. He's a handsome man, grown from the handsome boatbuilder of twenty years ago, and the handsome boy who moved here with his parents, E. B. White and Katharine S. White, sixty years ago.

They take a seat on some planking ahead ofGrace,and soon people start coming up to say hello. One friend, named Bill Mayher, stands a few feet away and asks, with a deep look, "So, how are you doing?"

"Pretty good," Joel says.

Then another friend comes up, looking concerned, even a bit afraid.

"How are you?"

"Good," Joel says. He smiles, says he'd been to "Thoracic Park," that he'd asked the doctor if he knew the difference between a "lobeotomy" and a "lobotomy," and that the doctor had said it was just a matter of a different spelling. He laughs a bit shyly.

Of course there's a deep affection for Joel among these people, his friends, those he's sailed with, people he's employed and taught about boatbuilding or boat design. Many feel they've been touched by him in some way. Joel is described as brother, father, friend by them. He's someone who creates beautiful boats in a place where people appreciate beautiful boats.

"How are you feeling?" someone else asks.

"Pretty good," Joel says, smiling, glancing away.

I've known Joel White since January, when I toured the coast of Maine looking for a boatyard where I could watch the construction of a wooden boat. When we met, Joel had just found out that he had cancer, but he didn't say anything about it. He showed me some of the projects at the yard. The hulls ofGraceandLindawere being planked then, and so was a Buzzards Bay 25, another of Joel's traditional but modern renditions, in this case a Nathanael Herreshoff boat. We looked in onEasterner,a 12-Meter racing sloop built in the late 1950s and once a candidate for the America's Cup, undergoin g a thorough rebuilding of the hull. Joel drove me to other boatyards in Brooklin, to Eric Dow's shop, where they were building anAraminta,an L. Francis Herreshoff design from the era ofQuiet Tune,and to Doug Hylan's shop, where he and his crew were putting new frames, or ribs, in an old sardine carrier being restored and converted into a yacht. He took me to junior Day's shop, where that seventy-five-year-old boatbuilder was shaping out the keel for a 24-foot lobster boat. Joel and I got sandwiches at the General Store and stopped to have lunch in the parking lot of his yard, where it was snowing lightly, and we talked about nature -- I told him about when I'd trained dolphins, and when I let a giant sea turtle go in Nantucket Sound, and Joel told me about how on another snowy day, the kind of storm with big flakes, he'd seen an eagle soar down near the windows of his design studio.

And we also talked about writing, and about his dad. I'd been teaching journalism and writing for several years as a college lecturer, and I said that I'd used E. B. White'sElements of Stylein courses. When I quoted from it, or rather misquoted, saying one of the rules as "Cut unnecessary words," Joel corrected me, saying,"Omitunnecessary words." He told me his dad said that Professor Strunk omitted so many words he was left to repeat himself: "Omit unnecessary words, omit unnecessary words, omit unnecessary words!" Joel said with a little laugh. It was such a pleasure to talk about both boats and writing. At the end of this visit, while I stood in Joel's office, a third-floor studio with a spectacular view of the harbor, I asked him if he was the boy in E. B. White's essay "Once More to the Lake," as tender a look of a father to a son as I'd ever read. Joel said he was, and then looked down so that the visor of his hat covered his eyes.

After that day, I was also someone who'd been given something by Joel, through the mere pleasant experience of talking about boats and writing. For a good day can be an aesthetic experience in itself.

Now at the launching, in between the greetings, Joel and I talk again. The yard has come a long way from the time he'd taken it over, thirty-five years ago. Since Steve had begun running the yard during the 1980s, business had increased by three or four times. Steve had added on, and bought the Travel-lift, for $80,000 -- "Something I would have had a lot of trouble doing," Joel says.

Steve had taken over at the right time. "I've been very lucky in my life," Joel says, "that things have come along at the right time."

This seems a bit peculiar, for someone to say how lucky he's been, just after having a section of his lung removed. But the remark struck a chord too. I had read that E. B. White also thought of himself as lucky and believed in his luck, even pointing to the date of his birthday, July 11, 7/11, as a symbol for it. Once when asked what a writer needed to be successful he had said, "Be lucky."

Graceis in the slings of the Travel-lift, her stern toward the water, her bow pointed at the crowd, the ribbons streaming. Frank and Grace Henry walk over and stand under the bow, and their family gathers nearby. Frank Henry thanks the crew, and points out Bob Stephens, whom he'd known at another yard in southern Maine. Bob had made the project all the more enjoyable, Henry says. He thanks Joel for the design and for the experience of working with him."Gracewill be staying right here in Center Harbor," Henry says, "where everyone can see her."

Then Grace Henry speaks. She tells about being on their yawl and coming uponEllisha.She says she saw the Center Harbor 31 when they were building it, "when it was on its belly." It had looked awfully big then, she says, and they told her it would look smaller in the water, but still she's not sure. Grace Henry takes a slip of paper from her pocket and reads it:

"May she bring pleasure to her captain and crew,

May she be well found and fast,

May she be the envy of all,

I name herGrace."

She swings a bottle of champagne at the stem, and swings again. Cheers go up, hands are raised in applause. Cameras are held high. The Travel-lift starts up with a cloud of smoke, and beeps its way down the tracks of the dock.Graceis then lowered gently into the water, like a nurse setting a baby into a bed. The slings go slack, the boat is floating, and there are more cheers.Graceturns and motors off into the harbor, and soon the sails are rising up the mast.

Lindais next. More people come up to see Joel. Allene is next to him. They met when Joel was in college, at MIT, she says. She'd been studying journalism, and now writes food columns for newspapers in Bangor and Portland. Allene had in the early years worked at the yard, keeping the books. She says that when they first put a phone in, she spent a lot of time looking for him -- "It's really easy to get lost in a boatyard." But Allene says she doesn't know much about boats, that she stays away from them. Her boys are into boats, with Steve running the yard and John working as a fisherman. Allene is more interested in literary things, as is her daughter Martha, a writer -- though Martha is also married to a man who owns a boatyard.

"It must have been nice to see Joel's career develop," I say.

"He was good from the beginning," she says.

When the Travel-lift positionsLindaby the dock, Alan Stern and Brian Stern stand under the bow. They're a small group, after the Henrys. And Alan Stern's day is tempered with frustration because the jib roller isn't working, and they won't be sailing the boat very far. Stern says he hadn't known there would be this kind of celebration at the launching. But he too thanks the crew, and Joel, and finally says, "This is the most beautiful boat I've ever seen in my life."

There's no bottle breaking this time, only the sound of the Travel-lift starting up again.Lindaswings down the dock and into the water. They motor over to the main dock and continue loading the sails. EventuallyLindaheads out, but only under a mainsail, and it's a haphazard ride.

Graceslides through the harbor on repeated runs. The Henrys sail it, and the Henry's children sail it, and so do various crew members, deftly turning and pulling up to the dock. There are cameras going off, shouts of praise.

At the shop, people line up for the buffet and then sit out by the seawall to watch. Joel makes his way down the dock and the ramp. Leaning on his crutches, he looks atGracesail by. One of those who'd been sailing onGracegoes up to him and says, "Those are beautiful boats!"

"Not too bad," Joel says. A few moments later someone else turns to him and says, "That's an incredible boat!"

"It's a nice boat," Joel says.

You had to wonder about this response too, so muted. We live in an age of fist pumping and selfglorification, of unselfconscious self-promotion. A nice boat?

But then again, this is the son of the man who wrote the story about the spider that wrote "humble" in the web.

Tracing the lineages of boats is like tracing the lineages of songs. It's a matter of influences. A sheer line or bow profile is transposed, and transformed, personalized and made original. In the case ofGrace,and before her,Quiet Tune,you could trace a line back to a 14-foot Bermuda racing dinghy calledContest.A fast boat,Contestwas also beautiful to look at because of its shape, particularly because of the hollow or reverse curves of the waterlines.

Nathanael Herreshoff, the greatest of boat designers, creator of many America's Cup winners at the Herreshoff Mfg. Co. in Bristol, Rhode Island, may have seenContestwhen he spent a winter in Bermuda in 1911. Herreshoff was in his sixties then, and for many years had been designing racing boats with long overhangs (projecting ends) and waterlines with simple outward curves. He took such a boat to Bermuda in 1911, 23 feet long, with low freeboard (hull area above water) and long overhangs, but found he needed something that could fare better in the strong winds and waves.

Herreshoff returned to Bermuda in 1913 withAlerion III,a centerboard boat with lines that may have been a refinement of the shape ofContest.Twenty-six feet long,Alerionhad moderate overhangs, higher freeboard, and hollow curves at the bow, lines that are said to be of a transcendent beauty. The design ofAlerionwas a turning point for Nathanael Herreshoff, who in 1914 created the Buzzards Bay 12 1/2, and in 1916 its enlargement, the 20foot Fish Class sailboats. EnlargingAlerion,Herreshoff in 1914 designed the Newport 29, though it was a full-keeled hull and not a centerboarder. Five Buzzards Bay 25s were launched in 1914. A longer and sleeker version ofAlerion,the Buzzards Bay 25 is said to be Nathanael Herreshoff's favorite design, and is in the opinion of some, including Joel White, the most beautiful hull shape ever created. Maynard Bray, writing inWoodenBoatof the Buzzards Bay 25s and of the hollow-bowed boats of Herreshoff, recommends visiting the Herreshoff Marine Museum in Bristol to look at the Buzzards Bay 25Aria,suggesting that it will be an "almost religious experience...I guarantee she'll take your breath away."Alerioncan be seen in the Watercraft collection at Mystic Seaport Museum.

One of Herreshoff's sons, Sidney, used the half-model forAlerionto create the Fishers Island 31. Twelve of those 44-feet-long boats were built between 1927 and 1930. One of them,Cirrus,was still sailing in Center Harbor in the 1990s, and stored at Brooklin Boat Yard.

Another of Herreshoff's sons, L. Francis, worked for the designer W. Starling Burgess during the early 1920s and opened his own design firm in Marblehead, Massachusetts, around 1926. It's been said that while Nathanael Herreshoff was the consummate engineer (studying at MIT, developing steam engines, developing America's Cup yachts), L. Francis was more the artist, and that because he was so concerned with aesthetics he lacked the competitive instinct to build winning racers. As a boy he watched his father drawing and making models -- his bedroom was next door to his father's design room -- and as an adult L. Francis Herreshoff showed both the influence of his father and an originality in his own work. Over a period of forty years he created about 107 designs, ranging from decked canoes to schooners to power cruisers. He is said to have designed some of the most beautiful boats ever created -- the 57-foot ketchBounty,designed in 1934; the 72-foot ketchTiconderoga,1936; the canoe yawlRozinante,1956. The younger Herreshoff's trademark was the ketch.

Quiet Tunewas 29' 6" long, with hollow waterlines and a transom with a wineglass shape. Designed for Ed Hill, a marine hardware representative from Newcastle, Maine, it was built at Hodgdon Brothers in East Boothbay in 1945. Hill usually sailed it in the late afternoon. (The firstAraminta,known as the successor toQuiet Tune,was also built for Ed Hill, by Norman Hodgdon in 1954; also a ketch, and a daysailer,Aramintawas three feet longer and had a clipper bow rather than a spoon-shaped bow.)Quiet Tunehad several owners, including one in Newport Beach, California, before she was donated to Mystic Seaport Museum in 1993.Aramintaalso visits there occasionally, and the two boats often lie side by side.

L. Francis'sQuiet Tuneis said to be a narrower, deeper version of his father's Buzzards Bay 25 design, though with a ketch rig -- and soAlerionis a presence in the boat. ButQuiet Tuneis also within a family of 20- to 30-foot daysailers built in New England beginning in the mid-1930s. The 20-footers Popeye and Mink were designed by Charles Hodgdon and built at Hodgdon Brothers around 1935. They were followed by the Boothbay 20, designed by Geerd Hendel and built by Hodgdon Brothers and other builders from 1935 until about 1960 (two of these,IndiaandBlue Witch,are housed at Brooklin Boat Yard). In 1936 Starling Burgess designed the Christmas Cove daysaller, also built by Hodgdon Brothers. In 1937 the Yankee One Design appeared, built by Quincy Adams and various other New England yards. In 1938 L. Francis Herreshoff designed theBen Ma Cree,built by Britt Brothers in West Lynn, Massachusetts. Sonny Hodgdon builtQuiet Tunein 1945, in East Boothbay; then, in 1954 he came out with his own design for a daysaller with lines similar to Quiet Tune's and said to be just as beautiful, the Hodgdon 21 -- one of them,Nasket,has been kept at Brooklin Boat Yard for many years.

When Frank Henry choseQuiet Tuneas the basis for his own boat, Joel White made an analysis of the design. He found that for her sizeQuiet Tunehad weak sailpower, that she was underrigged. He knew that if he improved the stability of the boat, by changing its underwater configuration, he could increase sail area, and thus the power and speed -- and also perhaps improve looks.

Quiet Tunewas built by traditional plank on frame construction, and had a long keel with a rudder attached to the aft end in cross section, the hull was shaped like a wineglass, and even tending toward the Y shape. This was a design that made for a high center of gravity. It also had a rather low "form stability," because of the "slack bilges," the flatness of the sides of the hull just below the waterlinewhich meant that when the boat heeled from the vertical, less volume was being put into the water and stability was decreasing.

Joel White designed an improved hull that was more cupshaped and that had a few inches more beam thanQuiet Tune.Instead of a long keel faired into the bottom of the hull, made of heavy timbers and lead, Joel White designed a hull with a fin keelan appendage that looks like a shark's fin, narrow yet deep, and which had a cigar-shaped bulb of lead at the bottom. His design would not be built of oak frames and cedar planks, but instead of light strips of cedar covered with glued layers of thin mahogany veneers running diagonally -- a relatively new construction method called cold molding. Because the hull of the Center Harbor 31 would be lighter than the originalQuiet Tunehull, more lead could be added to the bottom of the fin keel, lowering the center of gravity and increasing the stability. Yet the Center Harbor 31 has about the same displacement -- 7,916 pounds -- asQuiet Tune.The changes, and increased stability, enabled him to increase sail area, from 352 to 441 square feet for a gain of 20 percent withGrace.The gain onLindawas even greater. A spade rudder was at the aft end of the waterline on both boats, a device that improved maneuverability.

The lowered vertical center of gravity, to 1.5 feet below the waterline, allowed Joel to make improvements in another area where he found shortcomings, the cockpit. Sailors and passengers inQuiet Tunesat on the floor of a shallow, self-bailing cockpit, in a somewhat awkward position due to the placement of backrests, and it tended to be an uncomfortable ride after a while. But on the Center Harbor 31 the cockpit was made deeper and non-self-bailing, and there were teak seats with a molded shape, and backrests, canted at a comfortable angle, that also served as the coamings, or outer walls, of the cockpit.

Quiet Tunewas an austere boat, in keeping with the designer's belief that sailing should be a simple pursuit, a diversion from the trappings and trials of modern life, a way to observe and interact with the weather. The Center Harbor 31 was not quite so austere. In the cabin was a galley with a stove and sink, seats with cushions, a chemical toilet onGraceand an enclosed head onLinda.

Below waterGraceandLindawere modern, with their altered shapes and increased stability. The cabin interiors tended toward the modern too, but above waterGracein particular looked very reminiscent ofQuiet Tune,with its ketch rig, its lovely sheerline, and the scoop of its hollow bow.

1938

E. B. White loved boats from the time he was a boy. His father, Samuel Tilly White, gave him an Old Town canoe for an eleventh birthday present, and it was used during vacations at the Belgrade Lakes in Maine. His older brothers built a 16-foot launch from blueprints and precut frames, and Samuel White hired a boatbuilder from Long Island to help them trim the deck, fit the coamings, and caulk the seams. They named the boatJessie,after their mother, and moved it to Maine by train and to the Belgrade Lakes by wagon. In the introduction to hisLetters,White wrote of how "we would all crowd into her, nestling together in the tiny cockpit like barn swallows in their nest, and cross the pond in all kinds of weather."

After he left a job at an advertising agency and during the summer before he began writing atThe New Yorker,E. B. White bought a 20-foot catboat, naming it Pequod. It had "accommodations for one, a simple gaff rig, a marvelous compactness," he wrote in a "Notes and Comment" section ofThe New Yorker.He used it to make trips along the Long Island shore, "a remote and lotusscented land," usually going alone. He preferred sailing alone.

He married Katharine Sergeant Angell, the fiction editor atThe New Yorker,in 1929. Divorced, with two children from a previous marriage, she gave birth to a third child, Joel McCoun White, on December 21, 1930. E. B. White was born on a lucky day -- his son was born on the solstice, the day that symbolizes the beginning of life. The birth was a difficult cesarean, and at one point, when it was thought that Katharine might die, a nurse whispered in her ear, "Do you want to say a little prayer, dearie?" "Certainly not," she answered.

On New Year's Eve, Katharine and Joel White were still in the hospital. Speaking through the persona of his dog, E.B. wrote in a letter:

Dear Joe:

Am taking this opportunity to say Happy New Year, although I must say you saw very little of the old year and presumably are in no position to judge whether things are getting better or worse...I walked around the block with White just before he went to the hospital with Mrs. White so you could be born, and we saw your star being boisted into place on the Christmas tree in front of the Washington Arch -- an electric star to be sure, but that's what you're up against these days, and it is not a bad star, Joe, as stars go.

He also began writing poems to his son, some of which would appear in the collectionThe Fox of Peapack,published in 1938. "Apostrophe to a Pram Rider," a song of advice, included the lines:

Some day when I'm out of sight,

Travel far but travel light!

Stalk the turtle on the log,

Watch the heron spear the frog,

Find the things you only find,

When you leave your bag behind;

Raise the sail your old man furled,

Hang your hat upon the world!...

Thank the God you've always doubted,

For the gifts you've never flouted;

...Joe, my tangible creation,

Happy in perambulation,

Work no harder than you have to.

Do you get me?

In "The Cornfield" the author takes a walk, and speaks of the inspiration his son gives him:

...My son, too young and wise to speak,

Clung with one hand to my cheek,

While in his head were slowly born,Important mysteries of the corn.

And being present at the birth

Of my child's wonderment at earth,

I felt my own life stir again

By the still graveyard of the grain.

In "Complicated Thoughts About a Small Son," another of theFox of Peapackpoems, he again speaks of inspiration and wonder, but also of death, and another theme he would continue to explore, the transposition of generations, the presence of the father in the son.

In you, in you I see myself,

Or what I like to think is me:

You are the man, the little man

I've never had the time to be.

In you I read the crystal line

I'll never get around to writing;

In you I taste the only wine

That makes the world at all exciting;

And that, to give you breath and blood

Was trick beyond my simple scope,

Is everything I know of good

And everything I see of hope.

And since, to write in blood and breath

Was fairer than my fairest dream,

The manuscript I leave for death

Is you, who supplied its theme.

In 1935 when Joel was four, E. B. White bought a 30-foot cutter namedAstrid.One of Joel's earliest memories was of seeing the boat near a dock at City Island, New York. White sailedAstridto Maine, where he and Katharine had bought a house and barn on Blue Hill Bay in North Brooklin. There in the summers onAstridthey took short sails and went mackerel fishing.

In 1938 they took up year-round residence in Maine. E. B. White would later call the move "impulsive and irresponsible" because he wasn't sure how he'd make money, or how it would be for his son to leave a

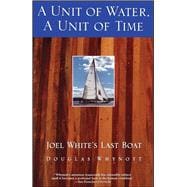

Excerpted from A Unit of Water, a Unit of Time: Joel White's Last Boat by Douglas Whynott

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.