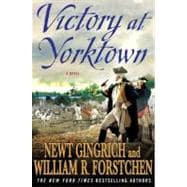

NEWT GINGRICH, recent Presidential Candidate and former Speaker of the House, is the bestselling author of Gettysburg and Pearl Harbor and the longest serving teacher of the Joint War Fighting Course for Major Generals at Air University and is an honorary Distinguished Visiting Scholar and Professor at the National Defense University. He resides in Virginia with his wife, Callista, with whom he hosts and produces documentaries, including their latest, A City Upon A Hill.

WILLIAM R. FORSTCHEN, Ph.D., is a Faculty Fellow at Montreat College in Montreat, North Carolina. He received his doctorate from Purdue University and is the author of more than forty books. He is the New York Times best selling author of One Second After. He resides near Asheville, North Carolina, with his daughter, Meghan.

Praise for the works of Newt Gingrich and William R. Forstchen:

“Masterful storytelling.” --William E. Butterworth IV, New York Times bestselling author of The Saboteurs

“Creative, clever, and fascinating.” --James Carville

“Compelling narrative force and meticulous detail.” --The Atlanta Journal Constitution

“Gingrich and Forschten write with authority and with sensitivity.” --St. Louis Post Dispatch

“Grim, gritty, realistic, accurate, and splendid, this is a soaring epic of triumph over almost unimaginable odds.” --Library Journal on To Try Men’s Souls

“With each book… Gingrich and Forstchen have gone from strength to strength as storytellers.” --William Trotter, The Charlotte Observer

“The authors’ research shines in accurate accounts of diplomatic maneuvering as well as the nuts-and-bolts of military action.” --Publishers Weekly

“The writing is vivid and clear.” --Washington Times

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.