Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Introduction | p. 3 |

| Before the Storm | p. 9 |

| Inheritors of Slavery | |

| Twelve Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States, 1941 | p. 13 |

| North Toward Home | |

| 1967 | p. 32 |

| Notes of a Native Son | |

| 1955 | p. 41 |

| A Pageant of Birds | |

| The New Republic, October 25, 1943 | p. 57 |

| I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings | |

| Harper's Magazine, February 1970 | p. 61 |

| Opera in Greenville | |

| The New Yorker, June 14, 1947 | p. 75 |

| Into the Streets | p. 105 |

| America Comes of Middle Age | |

| He Went All the Way, September 22, 1955 | p. 111 |

| Upon Such a Day, September 10, 1957 | p. 113 |

| Next Day, September 12, 1957 | p. 115 |

| The Soul's Cry, September 13, 1957 | p. 117 |

| American Segregation and the World Crisis | |

| The Segregation Decisions, November 10, 1955 | p. 120 |

| The Moral Aspects of Segregation | |

| The Segregation Decisions, November 10, 1955 | p. 123 |

| The Cradle (of the Confederacy) Rocks | |

| Go South to Sorrow, 1957 | p. 129 |

| Parting the Waters: America in the King Years | |

| 1988 | p. 150 |

| Prime Time | |

| Colored People, 1994 | p. 154 |

| Letter from the South | |

| The New Yorker, April 7, 1956 | p. 161 |

| Segregation: The Inner Conflict in the South | |

| 1956 | p. 167 |

| Travels with Charley | |

| 1962 | p. 203 |

| Liar by Legislation | |

| Look, June 28, 1955 | p. 209 |

| Harlem Is Nowhere | |

| Harper's Magazine, August 1964 | p. 214 |

| An Interview with Malcolm X | |

| A Candid Conversation with the Militant Major-domo of the Black Muslims, Playboy, May 1963 | p. 218 |

| Wallace | |

| 1968 | p. 235 |

| Mystery and Manners | |

| 1963 | p. 267 |

| The Negro Revolt Against "The Negro Leaders" | |

| Harper's Magazine, June 1960 | p. 268 |

| The Mountaintop | p. 281 |

| "I Have a Dream ..." | |

| The New York Times, August 29, 1963 | p. 285 |

| Capital Is Occupied by a Gentle Army | |

| The New York Times, August 29, 1963 | p. 288 |

| Bloody Sunday | |

| Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, 1998 | p. 292 |

| Mississippi: The Fallen Paradise | |

| Harper's Magazine, April 1965 | p. 318 |

| This Quiet Dust | |

| Harper's Magazine, April 1965 | p. 328 |

| When Watts Burned | |

| Rolling Stone's The Sixties, 1977 | p. 346 |

| After Watts | |

| Violence in the City--An End or a Beginning? The New York Review of Books, March 31, 1966 | p. 348 |

| The Brilliancy of Black | |

| Esquire, January 1967 | p. 352 |

| Representative | |

| The New Yorker, April 1, 1967 | p. 367 |

| The Second Coming of Martin Luther King | |

| Harper's Magazine, August 1967 | p. 370 |

| Martin Luther King Is Still on the Case | |

| Esquire, August 1968 | p. 389 |

| Twilight | p. 409 |

| "Keep On A-Walking, Children" | |

| New American Review, January 1969 | p. 413 |

| "We in a War--Or Haven't Anybody Told You That?" | |

| Report from Black America, 1969 | p. 450 |

| Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny's | |

| New York, June 8, 1970 | p. 463 |

| Choosing to Stay at Home: Ten Years After the March on Washington | |

| The New York Times Magazine, August 26, 1973 | p. 478 |

| A Hostile and Welcoming Workplace | |

| The Rage of a Privileged Class, 1993 | p. 486 |

| State Secrets | |

| The New Yorker, May 29, 1995 | p. 499 |

| Grady's Gift | |

| The New York Times Magazine, December 1, 1991 | p. 517 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 529 |

| Permissions Acknowledgments | p. 531 |

| Index | p. 533 |

| Table of Contents provided by Syndetics. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

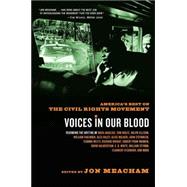

Excerpted from Voices in Our Blood: America's Best on the Civil Rights Movement by Jon Meacham

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.