The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

CHAPTER ONE

Crossing the Threshold:

First Days

I was as naive as green could be.

--Lorraine Bertosa, Cleveland, Ohio

For my very first day in union construction I was sent to a bank in downtown Boston where a journeyman needed a hand pulling wire. Arriving early with my new tools and pouch, I knocked on the glass door in the high-rise lobby and explained to the guard that I was a new apprentice working for the electrical contractor. He refused to let me in. So I sat down on the tile floor, my backpack and tool pouch beside me, and waited for the man whose name I had written down alongside the address and directions on a piece of paper: Dan.

The guard explained to Dan later that he'd figured I was a terrorist planning to bomb the bank. In 1978, that seemed more likely than that I might actually be an apprentice electrician.

My eagerness and ignorance that morning almost combined in disaster. After explaining that I was to push the metal snake, with different colored wires taped to it, into a pipe, Dan left for the location where the wires would be coming out. As vigorously as I could, I began to push in yard after yard of the thin looping strip of metal. About fifteen seconds later, I heard Dan scream. I froze. In moments he reappeared, his ruddy complexion ashen. It hadn't occurred to him that I had to be told to wait until he was at the other end of the pipe and gave a signal, before I pushed a metal snake into a live electric panel--and that pulling wire requires slow, methodical teamwork for safety.

The following day I went out to a "real" fenced-in construction site, bustling with men who worked at trades I'd never even heard of. It was new construction at a chemical plant--an unusually dangerous job, though I had no idea of that at the time. Installations were all stainless steel, as required in hazardous locations. A man from the plant kept reminding us to run immediately if we ever saw a certain pipe drip. Something corrosive in the environment was dissolving the glue on the soles of my new boots and turning dimes in my pocket green. The crew was no more welcoming.

--Susan

Women who walked onto construction sites in the late 1970s and early 1980s to begin their apprenticeships in the trades carried more than the usual new job anxiety and disorientation. Most were coming from traditionally female occupations. Not only were the craft and tools unfamiliar, so too were the culture and organization of the construction workplace.

Women used to jobs where two weeks' notice is the norm for hiring or layoff were shocked to learn that, by construction industry standards, a day's notice is considered generous. Those who couldn't afford to risk buying all the necessary tools and work clothes until a job was definite had very little time to get prepared.

A full year after her 1978 acceptance into the carpenters union in Kansas City, Kathy Walsh's phone awakened her unexpectedly at 4:30 one morning. A single parent of three not quite able to manage on her secretarial wages, she was told she had an hour and a half to get to her first construction job.

I WAS LIKE, AH, AH, I can't do that. I mean it wouldn't work with my babysitter and I didn't know where I was going and I didn't have my tools and I didn't want to go off and just not show up at my job. It was like-panic! And he goes, "Well, if you can't do it today, I guess you don't want to be a carpenter."

After a lot of pleading, she talked the apprentice coordinator into giving her a day's grace.

I WENT OUT THAT DAY AND spent every penny I had on a tool pouch. I didn't have boots. Had to buy a pair of work boots and the tools. The list that the apprentice coordinator had given me was very extensive, probably eighty carpenter tools. When you're first starting out you don't know that these are drywall tools and you don't need those on a concrete job. And these are finish tools. I got as many as I could. I'd been trying to get them all along at garage sales and swap-and-shops. I had my little toolbox and I got my boots and bought a pouch and didn't sleep at all that night.

I don't remember who was babysitting for me at that time, but I either had a friend or made arrangements to take my son early. [I left] at 4:30 in the morning because I didn't know where I was going and I didn't want to be late. I was so nervous, I was sick to my stomach almost. I had directions to this job-site and I had somebody's name. I didn't know what they would want me to do or anything. I had been practicing what I thought was hammering at home, tap, tap, tap, just nailing nails into a two-by-four.

It was really a big thing for me to walk away from the job that I had. The people I was working for were very, very supportive and said, Kathy, go for it, it's an opportunity If it doesn't work out, you let us know.

Thank God, because I went back to work for them many times.

Women across the country in different trades report similar long waits of six months to a year between acceptance into an apprenticeship and an actual job offer, often while men brought in at the same time went out to work right away. Apprentices usually don't become full union members until they have worked their probationary hours, generally ranging from three months to a year depending on the local. Keeping women in a pool, available for work but not accumulating work hours allowed unions and contractors to be ready to meet compliance requirements without bringing in female members they wouldn't "need" if court challenges to affirmative action succeeded in having the guidelines eliminated. Another factor in this delay likely was that federal regulations bringing women into apprenticeships became effective in June 1978, but the effective date of the regulations for affirmative action on jobs was not until May 1979.

Offering a woman a job--whether she took it or not--counted as a "good faith effort" toward affirmative action. No one checked whether the offer was made under circumstances that made it unrealistic for her to accept, or after such a long wait that she was likely to have found other work. For all the women who did switch their jobs on a day's notice, obviously there were many who could not, and who were recorded on forms as turning down an apprenticeship or a job offer.

Whatever her desire to blend casually into the workforce on her first day, a tradeswoman walking onto a construction site in the late 1970s had all the invisibility of a flashing neon sign. Raised in the Bronx, Melinda Hernandez had become a jeweler's apprentice after leaving college, but found the work exploitative. She participated in a government-funded, two-month training program in construction skills for women that she'd heard about from a friend, and became one of the first four women in the union electrical apprenticeship in New York City. She was not only female, but Puerto Rican and 5'2".

I HAD A LITTLE RED TOOLBOX. I looked like Little Red Riding Hood coming onto the job. It was funny because I had been taught by the women at All Craft, they're going to try to test you, so don't take any lip. You just let them know that you're there to do a day's work and to learn a trade.

I was running late because I couldn't find the job. When I walked into the building, I asked for the electricians' shanty. The guys looked at me like, What the hell is she doing here? Like, they heard we were coming, but it was never going to be real, it was never going to materialize. And there is this little woman with a toolbox.

The job was 70 percent complete. The walls were up, the windows were in, and they were just roughing out internally. When I got to the electricians' shanty and I opened the door, the foreman was sitting at the desk. He was about 60 and he was gray, all this silver gray. He looked at me and he says, "Yes, little girl, what is it? Did your father leave his tools home?" He was serious. He wasn't being sarcastic. I think the shop just sent me and didn't inform him, to kind of play this game, Let's see how he reacts, you know.

I was 22, but I looked like 15 or 16 at the time. I said, "I'm here to report for work. I'm an apprentice."

Since construction sites are off limits to the public, most new tradeswomen's first day on the job was also their first glimpse of its sights, smells, and sounds. Just navigating the worksite could be a series of new experiences and challenges.

Barbara Trees had gained some experience with carpentry tools and a taste of working on an all-male crew before beginning her apprenticeship in 1980. As a low-wage artist's assistant, she worked on a replica of the Brooklyn Bridge. Desire for a job that was physical and that paid well enough for her to be a self-supporting single woman without a college degree--and "the momentum of women around me"--drew her into the union.

I DON'T KNOW HOW I GOT this idea, but I actually thought that I was going to be building some nice furniture. I know Mary Garvin at Women in Apprenticeship told me, You have to like working outdoors, you're working in all kinds of weather, it's heavy work, and sometimes it's dangerous. I know they told me all that, but when I headed out for my first jobsite, I was in shock. It was a rude awakening.

I came onto this big jobsite on Roosevelt Island. The tram, this little aerial thing, took me out there. They were building a subway, okay, but I had not a clue. The foreman came up and he shook my hand. It was not like he killed me instantly, which is what. I thought was going to happen. There was an empty building across the way I looked over and thought, It's the only thing that's standing around here. That must be what we're going to work inside of. So I said, "Is that where I'll be working?" He just laughed.

Then we went down into the hole, this dark pit. It was underground. They didn't have it lit very well and it looked just real scary. It was all wet. There was water everywhere. I was afraid I was going to slip and slide down this embankment. I always pictured myself as a pretty strong person and independent. I got into this situation and I was just really afraid. I was afraid to go down a ladder, so I asked him the safest way. I was checking to see if he laughed at me. But he just told me how to do it.

We got downstairs. I remember it was all rebar. They had put the rebar down already. I certainly didn't know that was the name of it, it was all those big metal things. I thought, My God, I'm going to have to walk across this. I was stumbling and thinking I'd go right down through it.

Male apprentices sponsored into their local union by their father or uncle had someone with years of experience making sure they went to their first job properly prepared--mirroring a familiar image. Most new tradeswomen lacked that advantage.

Helen Vozenilek was a strong athlete and tired of the minimum-wage jobs such as warehousing she'd held since dropping out of college. Finding a notice on the bulletin board at the YWCA about openings in the electricians apprenticeship, shortly after arriving in Albuquerque from the Northwest, was "pure luck." On her first job she improvised her tool pouch as best she could, and tried to stay calm when the foreman's brief jobsite tour included taking her up to the roof.

I DIDN'T LIKE HEIGHTS. I MEAN, we're not talking high at all--it was two stories--but I get to the edge and already I get that feeling like I was ready to throw up. At high places I get that sudden urge to jump, too. I don't know if other people get it, but it's split-second and then right away--it's not very serious at all. All those things would be going through me and I thought, Jesus, what am I doing here? I'm only two stories up and already I'm nervous.

On that tool belt, I didn't know where the tools went. I didn't know anyone that was in the trade to ask except this one woman and I wasn't going to call her up and ask her which pocket the screwdriver goes in! You know, they have the little thing that you hook the electrical tape on? Ah, geez, I didn't know--I was hanging tools from that little thing! This guy out there helped me set up the tool pouch and it looked better, but it looked obvious. You can tell a new tool pouch. Shortly afterwards, I backed a car over it to make it look used, because you just get too much ridicule.

The boss paired me up with this other guy who was real sweet. I didn't know anything, didn't even know which direction the toggle bolts go in. He showed me how to do something and I kept trying to suck up this toggle bolt. But I had the toggle going the wrong way! Of course, the thing wouldn't suck up and the hole was getting bigger and bigger in the sheetrock and Oh, my God!

Females in our culture learn early to avoid isolated situations with men. Yet most tradeswomen were put on jobs where they were not only the first but the only woman. Cynthia Long had met Melinda Hernandez as she waited on line--five days and nights camped out on the streets of New York--for an application to the electricians union apprenticeship, and again when new apprentices had been called into the union hall for an orientation and tool check. But Cynthia walked onto her first job alone, with a fear and strategy familiar to most women.

I HAD MADE A CONSCIOUS DECISION that I wanted to be perceived of as a professional person. I had my little work uniform from Sears and Roebuck, the dark blue chinos pants and the work shirt. I went dressed to work. My hair was pulled back and up out of the way so that I would have free movement of my head and not worry about getting my hair caught on something in the ceiling. I remember my pliers were Ideal pliers--they were amateur tools, the only stuff that I had.

I was scared. First there was this whole thing about finding the shanty. I had never, ever been on a construction site per se and certainly not the size of the construction sites that are typical here in New York. I didn't know where to go. One of the concerns high on my mind was my safety, was I going to be safe--in terms of rape. That clearly crossed my mind, Is this going to be something that I have to be concerned about and constantly fearful of?

Rumors skipped around the country via women's movement networks. Sara Driscoll, who also started her electrical apprenticeship in 1978, walked onto her first job with trepidation.

MY FIRST JOB WAS DOWN at the South Postal Annex, downtown Boston. Humongous site. I mean, this building went on for about three blocks, it was huge. And the first day I walked on that job I was really frightened. I wasn't frightened of the work. It was, What are these guys going to do to me, are they going to even let me be here?

I had heard some stories about some women in the trades down in the South. I remember one that really stuck in my mind was this woman in Texas who was a carpenter. They pounded her hands with a hammer, they broke her hands, that kind of stuff. I don't know if it was a true story. I don't remember where that story came from. I walked onto that job and there were probably 150 tradesmen from all the different trades, carpenters and tin-knockers and pipefitters and electricians and what-have-you's. And I was the only woman. And it was this humongous job.

Apprentices are supposed to be paired up with an experienced journeyperson whom they are required to follow into isolated mechanical rooms, poorly-lit basements, or anywhere else there is work to be done. Many situations normal to a construction job ring a caution bell for women. Deb Williams was 17 when she began her painting apprenticeship on a job at Harvard University.

THERE WERE SO MANY MEN on that job, I was afraid. I didn't want to get caught anywhere alone with any of these people because I didn't know them.

One guy, coming back from lunch, he's talking to me, Hi, Deb, how are you? How was your lunch?

Fine.

When we got into the lobby to take the elevator up to the department that we were working in, the elevator doors open. He got in and I stayed there. And the elevator doors closed--because I didn't know this person. I was damned if I was going to get in an elevator with a strange guy, just him and me--no way! To this day, he's my best friend and he'll tell you the same story. He goes, I got in that elevator, I'm saying, do I have B.O.? What's the matter? Did I do something to her?

I was leery of all men.

A short while later Deb was transferred to a bridge being sandblasted and painted.

THERE'S ONLY ABOUT TWENTY MEN on that job, which is totally different because now they're all grubs, they're all sandblasters. They're not all these nice white guy painters that you see on the label of paint cans. Now they've all got hoods on, it's freezing out--these are some rugged people.

We was hanging tops and when I was climbing on the steel girders I was on one side and my foreman was on the other side and the wind is blowing and I'm doing all I can to hold this thing. I'm not as strong as he is and the thing is ripping. And so I hooked my side. He said to me, "Deb, climb over me and get on the other side and hook it up." He's holding it in the middle. We're on our bellies on a girder and there's another girder about two feet above me. And he's telling me to slide over him across his whole body and get on the other side and hook it up. I said, "No."

He said, "Deb, you got to slide over me. It's the only way to go over there."

I said, "No." 'Cause I had to wedge myself between the beam and him. My body had to slam against his to get over. He says, "Do it fucking now. I'm holding this-thing. Slide over me!"

And whoosh, over I went and hooked it up. He goes, "Now was that so damn bad? I could have fallen off there. You're here to do a job."

My face was bright red. Even thinking about it now.

The situation was brand-new not only for the tradeswomen, but for their male co-workers as well. Not only had the men not worked with a woman on a construction job, many had little experience working with women on any job. For those with backgrounds in vocational schools and the military, the single-sex culture they'd spent their days in since puberty had suddenly been changed by federal regulation.

Men's discomfort with women's sudden appearance in their workplace took on many forms. To survive, tradeswomen quickly had to become stand-up improv artists with a flexible repertoire of responses. Maura Russell, a graduate of Smith College, began her plumbing apprenticeship on a medical research building in Cambridge, where men's reactions ranged from hostile to protective.

ON THAT FIRST JOB THERE were a couple of guys who, whenever I was within earshot, would get into this loud and graphic and disgusting rap about all the horrible things they had done to women. Glance over to see that you're there and kind of check out the reaction. I don't even think I knew their names. They were electricians. That was just the environment.

Definitely the kind of job [where] when you went out to the coffee truck--complete silence. You were really, really, really the oddball. Big time. Walking out of the building and going to the coffee truck and getting total silence--I mean conversations stopped completely and people stare at you the entire time you're there--that was bad.

I remember the first day on that job. It was dark because I wanted to be there early, make sure I wasn't late. It was fall. This little old stooped laborer met me and just said, "Oh, no. You shouldn't be standing out here. They're all going to be coming and they're all waiting for you." It was so scary. He says, "Come and wait over here."

He takes me to this little shed with no lights and closes the door. He pokes his head back in just before he leaves and says, "You know, they're waiting for you, but they're all going to be surprised. They're all wrong. They thought it was going to be a black girl." And then he closes the door.

I don't know what time it is, whether I should go out. Oh, scary as anything! I stayed in there for quite a while and then when I finally got the courage to open the door to God-knows-what, it was light. I was actually a little bit late at this point. Probably people had been working for five minutes or something, and I have to go out and find out where my boss is.

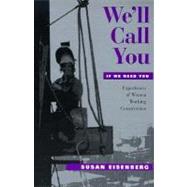

Copyright © 1998 Susan Eisenberg. All rights reserved.