Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| List of Illustrations | p. ix |

| Introduction: The Letter | |

| The Letter | p. 3 |

| Before | |

| Thomas Wentworth Higginson: Without a Little Crack Somewhere | p. 17 |

| Emily Dickinson: If I Live, I Will Go to Amherst | p. 35 |

| Emily Dickinson: Write! Comrade, Write! | p. 63 |

| Thomas Wentworth Higginson: Liberty Is Aggressive | p. 81 |

| During | |

| Nature Is a Haunted House | p. 101 |

| Intensely Human | p. 120 |

| Agony Is Frugal | p. 146 |

| No Other Way | p. 161 |

| Her Deathless Syllable | p. 182 |

| The Realm of You | p. 197 |

| Moments of Preface | p. 214 |

| Things That Never Can Come Back | p. 230 |

| Monarch of Dreams | p. 247 |

| Pugilist and Poet | p. 255 |

| Rendezvous of Light | p. 264 |

| Beyond the Dip of Bell | |

| Poetry of the Porfolio | p. 271 |

| Me-Come! My Dazzled Face | p. 288 |

| Because I Could Not Stop | p. 302 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 319 |

| Notes | p. 323 |

| Selected Bibliography | p. 373 |

| Emily Dickinson Poems Known to Have Been Sent to Thomas Wentworth Higginson | p. 385 |

| Emily Dickinson Poems Cited | p. 389 |

| Index | p. 395 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

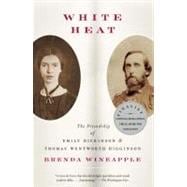

Excerpted from White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson by Brenda Wineapple

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.