|

1 | (69) | |||

|

70 | (23) | |||

|

93 | (24) | |||

|

117 | (23) | |||

|

140 | (33) | |||

|

173 | (40) | |||

|

213 | (21) | |||

|

234 | (30) | |||

|

264 | (27) | |||

|

291 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

PART ONE: THE WHITE MAN DECLARES HIS LOVE

Something startled Palle as he floated into the numbness of his afternoon's tropical snooze up on the breezy gallery where the damaging rays of sun just missed his toes. He opened his eyes.

Then he heard it again. A car horn. It was Simpson at the gate. Palle would wait a minute. Someone would open it. He gazed past the drooping white wooden gingerbread to the palm fronds. Beyond that was the sky, a wet, brown tropical sky that looked as if it wanted to perspire raindrops. But a faint fuzzy white sun held its place and the rain would not come. He could see little segments of dark blue ocean. Port-au-Prince was out there too. It would be there when he wanted it. Not this afternoon. Too hot.

The horn droned a long note. Palle realized he would have to do something. So he stood up, causing the white wicker chair to creak. He walked to the white wooden banister so that they could see him, the white man, standing up.

Little Jean-Jean appeared from somewhere below, running down the driveway to the gate. Terrible to run like that in this heat, Palle thought. Palle had not asked him to run. He didn't even like to see it. Jean-Jean struggled with the meager weight his small boy's body offered and slowly managed to slide the black steel door open.

Simpson drove his car into the shade of the well-gardened little circle and, getting out, shouted through the red hibiscus, as though reading Palle's mind, "Don't even bother to stand up. It's too hot."

"Come on up," Palle shouted down gratefully. Simpson, seersucker drooping creaseless from his bony frame, stepped up to the porch, maneuvered around the comic Liautaud iron sculpture that greeted him, walked across the polished dark wood floor to the staircase with the big colored glass balls on each banister post, climbed the carpeted stairs, stopped to admire the Bigaud, went right past the huge green brush strokes of the Philippe-Auguste, and by the time he was out on the gallery, Faustin was standing there holding a tray with two sweaty coral-colored drinks.

Palle settled deeper into his wicker seat. "Faustin, is this the new punch recipe?"

"Mais oui,"declared Faustin, plunging his voice a perfect octave between the first and second word.

"Not the rum punch we had before last week?"

Again the same octave."Mais non."

"Ah, that's good. That's very good," said Palle contentedly, with such absolute faith in his world that he was in no hurry to test it with a sip. The concoction would be dry, sour, cold, perfect.

"And how's life at the consulate?"

"Not like this," said Simpson, sipping his rum punch. "So what is happening, Palle? I have a feeling my big favor was no favor at all."

"Yes, that's right," said Palle, smiling pleasantly. "A complete disaster. Maybe it has ruined my life." He chuckled slightly at the idea of ruin.

"So what happened to...What was her name?"

"Lanuwobi," Palle said, savoring the syllables as though recalling something erotic.

"Wonderful name. I couldn't figure out what it meant."

"Doesn't mean anything."

"Neither does 'Simpson.'"

"It came to her mother in a dream. Her mother was pregnant with Lanuwobi and she was sleeping, and the phrase 'La-nu-wo-bi' came to her in her sleep." Palle sipped. The startling acid of fruit juices seemed the only thing in the world that was cool, the only thing with a hard, crisp edge on a moist and heavy planet. Then, slowly, he gave in to the rum, dark and syrupy as the weather. He felt like dreaming. "I suppose I met her because I needed a haircut. Well, it was back when I was staying in the hotel, and there were two of them at the desk, and I always said, 'I need one of you to cut my hair.' They laughed a little. And then one night Lanuwobi said, 'I'll cut it,' and she came to my room and, oh, she was very, very nice."

Palle's eyes were closed and he was smiling.

Simpson finished his punch and put it on the white table and Faustin noiselessly reappeared, replaced it with a full one, and vanished.

"I think we should have one more punch," said Palle reflectively, "and then we should switch to these new rum sours -- yes, that will be very good. So she was the receptionist. And she has a very nice voice. You know, answering the phone and so forth. Very sweet. I was there for a long period doing that film. Did you see my Haiti film?"

"No. You should get a copy for the embassy."

"And then at some point I needed a haircut. And I thought it would be nice to have this haircut done by -- I had two choices. I had a little problem deciding. At that time we were just flirting. Lanuwobi was very flirtatious. But then there was another girl who was also very flirtatious, Mona. You might remember her. She was small and a waitress."

"Do you often do this haircut thing?"

"No, no. This is new. This was a new idea. And she said yes she would do that. But then I was waiting to see if that would happen. The next night she said that she had bought a pair of scissors. Then it all took place in room eleven. The suite, you know. And that was really the beginning of this affair. I persuaded her to stay for the night, and this was really the beginning. She did a nice haircut, I think..."

Palle started remembering those days, sneaking around the hotel like happily worried teenagers. The hotel manager, a drowsy-eyed, light-skinned young patrician, did not approve. It wasn't that she was half Palle's age -- the manager's wife was even younger -- but his employees were not supposed to be sleeping with the customers. Not being a man of great principles, the manager had compensated by making up a few. Hotel employees should not sleep with guests in the rooms.

At the time, the army was out shooting at night. You could hear the dull crack of gunfire echoing off the mountains -- sometimes single pops, sometimes rhythmic bursts. Sometimes bodies were found the next morning. Flies would find them first, later journalists. In the afternoon they would be taken away. Staff on night shift were allowed to spend the night in the hotel because it was too dangerous to try to go home in the dark. Palle could never explain to Simpson -- unless he had experienced it, which was hard to say -- the romance of lying in bed holding a woman and feeling so completely alive while somewhere out there was death, and the dangerous popping noise could be heard coming through the shutters with the still night air and the croak of tree frogs.

Lanuwobi lived with her mother downtown. What a remarkable scene. He would have liked to have filmed it. The white man going downtown in his white four-wheel drive to pick up his girlfriend, down there where the air was full of steam and rot. Her mother had a small food store not much bigger than a large closet. Lanuwobi's dark turquoise-colored bedroom was only slightly larger than her bed. What always stayed in Palle's mind, aside from the terrible smell from the grayish slime in the concrete sewer ditch that ran along the edge of the house with boards to step over it, was the huge television that no one ever watched because the house did not have electricity. They also had two large radios, only one of which could operate with batteries. It somehow seemed important to have these things even though, after eight P.M., Lanuwobi and her mother were alone in darkness in the little house and went to sleep until the orange dawn.

"I think from the very beginning our relationship wasmalvue.Tolerated but not good."

You visited the home?"

"Yes," said Palle, thinking again about the television.

"You went there for dinner?"

"No! Never. I would never eat there. This was a small place. Low middle class. But they had servants, of course. What a fantastically complicated system. There is another class that is servants for them. But it was in an area where -- it stank. I admired the way these people kept their dignity, but I couldn't eat there. She was a very nice woman, the mother. She looked like Bessie Smith, you know, the blues singer. Very dignified. A nice lady, gray hair. Very beautiful. Her daughter was spending the night with me. She knew this, but it could never be understood that way. It was always said that Lanuwobi was staying at the hotel because it was dangerous at night."

Her mother had warned Lanuwobi that she should get legally married. Lanuwobi talked to Palle about marriage. "Yes," Palle had said, "we could consider marriage at some point."

Then, the first problem: Lanuwobi asked Palle to stay at a different hotel. She said it was embarrassing to come down to breakfast together. Palle objected, "But I like this hotel."

"Mais, c'est malvue."

Palle understood"malvue."She was sleeping in a hotel with a white man. It made her look like a whore. So he checked into a small hotel in Petionville, a group of mountaintops named after a light-skinned elitist general, where the people with money lived on the hilltops and the people with none lived in hidden shacks on the slopes and climbed topside to beg. Lanuwobi spent the night with Palle in the Petionville hotel. The next afternoon she went back to her job as a receptionist. Palle stopped by for a rum at the bar and to visit with her a little. But the pouting manager with the limp lower lip, a man of about the same age as Palle's oldest son, summoned him into the chaotic little room he called his office. He had heard that Palle was sleeping with Lanuwobi in the little hotel in Petionville.

"Where did you hear that?"

The manager smiled. It occurred to Palle to point out that none of this was any of his business, but it was all so interesting, the way things worked here. How had he found out, and what was he going to say about it? The manager simply wanted Palle back in his hotel. Very happily, Palle moved back to his favorite hotel, and discreetly, Lanuwobi would appear in his doorway. Night after night he would spend in the breezy hotel suite with her young and generous body and the pop-pop of murder vaguely heard in the distance.

But after a few weeks the manager fired her, saying, "You evidently are no longer interested in the hotel business."

Palle was able to get her a job as a receptionist in another hotel. As he pointed out to the new manager, she had a very nice voice for the telephone.

rd

This feeling that she gave him started in bed, this sense of power, that he was a magical kind of man who could answer all her desires. Whatever she needed to be happy, he could supply it. He could see the appreciation in her young eyes that sparkled like polished black gems. He was neither rich nor powerful, but he had enough money and enough power for anything she needed. She lost her job. He got her a new job. She wanted to speak better English. He taught her to speak excellent English. She wanted to drive a car. He taught her and got her a driver's license.

But Lanuwobi was tired of beingmalvuein the hotel where they slept. She no longer had her mother's approval, because she could no longer furnish her with an excuse for spending the night in that hotel where she no longer worked. The mother did not want to be forced to know about their relationship. Perhaps they should get married? Lanuwobi believed in bargaining and felt that she strengthened her negotiating position by arguing that she had been spending her nights with him in spite of her mother. She had done this for him and was owed something for it.

Palle introduced her to the concept of "vacation." They would go south to Jacmel, to a rustic little hotel with a beach in a rocky cove where the water lay still and opaline blue, sheltered by dangerous, jagged black rocks running to a small sandy beach where no one ever walked. They could take off their clothes and feel alone in the world. Sometimes someone would stare from under a tree by the hotel, someone of such low standing that it didn't matter whether they were clothed or naked in front of him.

Each time they went, she insisted that he drive downtown and see her mother and ask permission. At the age of fifty-six, divorced three times, Palle was learning for the first time in his life to go courting. He felt himself very romantic and picturesque. Though at times courting was inconvenient, the mother always played her part so graciously that he came to enjoy it.

Dinner became very important. If he took Lanuwobi out for dinner and they didn't get back until morning, that was acceptable because they were out for dinner, which offered the possibility that it could have gotten too late to get back. He would drive his white car down to their home in the stinking neighborhood, and she would be waiting, in a new and wonderful dress. Palle was always amazed at her dresses. Where did she keep them? Some were sent by her sister in New York. She always looked beautiful. She always had colors and fabrics that showed off the soft blackness of her skin. When they left, he would explain to her mother that if it got too late, they would "wait until morning to get back" rather than risk it in the night. And the mother always nodded.

Lanuwobi had gone to hotelier school and learned flawless restaurant manners, and she could speak in beautiful nineteenth-century French, much finer than Palle's own awkward Scandinavian-accented French. Palle liked being in overdone Petionville restaurants with this strikingly beautiful, perfectly dressed woman with lovely manners.

Occasionally Lanuwobi would mention something about marriage, and Palle started discussing it with his friend Ernesto. Ernesto was a South American, a political refugee, it was always said. Ernesto also was taking out a black woman, though from a slightly lower social standing than Lanuwobi. Ernesto's face -- his delicate smile, his dark, molasses-colored eyes -- was a caricature of good-natured innocence. He was gallant. He also had to court his young woman, but he took to the role with a natural grace that Palle could not totally master. Ernesto had courted before. Palle's deeply curious, intelligent face always looked as though there was a suspicion of silliness. He was always a film director, a slight distance away from himself, viewing the scenes of his life, watching the white man. And he was not sure that these courting scenes were working. But Ernesto courted as if he were gliding through the steps of a well-rehearsed classical ballet. No outsider observing Palle and Ernesto would have guessed which one was the romantic and which one was the cynic.

Ernesto could make Palle laugh. "Palle," he would say, "the Haitian bourgeois all want these light-skinned women. But you and I are so white we can have the really black ones." They both smacked the table gleefully.

Before each move, Palle would consult Ernesto. "Palle, you must keep her family away. Keep them away from your doorstep, Palle." Neither of the two friends seemed to notice that Palle very rarely took Ernesto's advise.

Ernesto advised Palle that he should marry Lanuwobi, but that he absolutely had to make a prenuptial agreement. "You have to protect your property, Palle." Ernesto could not understand that Palle had no property. Only the rights to a few documentary films in Danish.

Ernesto had an airtight agreement drawn up with his young woman, and then they were married at a seaside resort north of Port-au-Prince. Palle was the best man. When he drove downtown to take Lanuwobi to the wedding, he did not want to get out of the car with his white linen suit and white shoes. But it had to be done. He had to step over the sewer and go to the door and chat with her mother. He stepped carefully. Lanuwobi was also dressed in white, but she didn't change to her white shoes until she got into his car.

At the wedding, Palle, the best man, delivered a speech in French, which he was a bit shy about. It was difficult to hear because a scuffle broke out while he was speaking. Ernesto had provided T-shirts to commemorate his wedding, and there did not seem to be enough of them, or some people were taking more than one. The food went the same way, Creole food for two hundred people consumed by fifty in a matter of minutes. The guests who were fighting about the T-shirts -- some shirts got torn in the tugging -- missed out on the food.

But to Palle and Lanuwobi it was a moving afternoon that made them think even more about getting married. Palle was hesitating. He certainly would have no prenuptial agreement. That was no way to have a romance. He would not even mention such a thing to Lanuwobi. But Lanuwobi would not have been shocked. She knew about prenuptial agreements. She studied every detail of Ernesto's carefully worded document. She was ready to negotiate.

At some point, they should get married, Palle thought. Palle had been best man for Ernesto, and Ernesto was to do the same for Palle. But for now, more interesting projects could be undertaken. "You know, Lanuwobi, with your intelligence, there is no point in these low-paying hotel jobs. I could help you do something else. What would you like to do?"

"You know what I would really like to do?"

"What?" Palle asked confidently.

"I have always wanted to own my own beauty salon."

Palle did not know anything about beauty salons. He asked Ernesto, who said, "Excellent idea. You should set her up in her own beauty salon. That would be a good move, and it would only cost you maybe five thousand dollars." Palle did not have five thousand dollars at the moment, but there were times when he did. Next time he did have a few thousand dollars extra, he could do this. He told Lanuwobi that he had decided that at the first opportunity he would get her a beauty salon. Another wish granted.

They moved on to rum sours. They were better, more tart. The air was hot, sweet, and sticky. Rum sours were cold and acrid. Palle sipped, and the muscles in his neck pulled the skin tight across his face. Faustin was standing next to him with the tray in his hand, as though waiting for this facial expression.

"Faustin, these sours are very sour.Trop aigre."

In Palle's household, full sentences were only whispered in the garden and the kitchen. Palle and his staff had no common language. He spoke in truncated French expressions and they replied in equally abbreviated Creole. Between statement and reply, a few seconds lay for deciphering -- just enough time to convince each side that the other was a little slow. Palle would quickly lose patience with this torturous exchange and break into longer sentences even though he could never be sure if such statements were understood. But his staff never made that mistake.

"Mais oui. TwÓ. TwÓ,"Faustin agreed, and shook his head disapprovingly."Pa sik."

"Pa sik!There's no more sugar? But I just..." Palle slowly got up and walked lazily into his bedroom and came back on the gallery with black-market Haitian bills, which he handed to Faustin. Wearily, as though reciting someone else's lines, he said to Faustin, "Now this should be enough for a month's sugar."

"Oui, Mesié"

"And you know I will be very angry if we are out of sugar again before the end of the month."

"Oui, Mesié"

Simpson reflected to himself on how Europeans seemed to be born with an instinct for colonialism. Americans had to learn it.

"This was when you helped me with my big mistake," said Palle to Simpson with a wry smile.

"Why did you want the visa?"

"She wanted it. I could get her the things she wanted. That was the relationship. Ernesto said no. He said they are better with no visa. Ernesto is really tough, you know."

"But I remember she was entitled to a visa. She had a father in New York."

"Yes. She had never met him. She had just learned about him, the long lost father, and she wanted to visit, and for some reason they wouldn't give her the visa."

"I remember. Just an INS screw-up," said Simpson.

"Yes, but I waited too long. I should have married her. She always warned me about that. But I thought I had all the cards. Ernesto knew."

Lanuwobi was not worried about getting to New York to see her father. She knew Palle would get her a visa. He could always do these things. He never said he could do something and then failed. Theblanscould always arrange things between each other. She understood that this visa would be her card to play, not his. And she warned him, "We should get married now. After I go to New York, things will be different."

Palle thought that if she had a visa, he could take her with him to New York -- when he wanted. They would not be limited to trips to Jacmel anymore. Through Simpson he had contacted a high official in the INS who had come to Haiti for one week to "look things over." Palle could do this for her. Take it right to the top. She had been applying for two years. He could have the case moved up in a few weeks.

"Thanks to you, of course," he told Simpson.

Simpson nodded and sipped.

pard

"I thought it would make life easier. I was very naive there."

It was springtime and Palle was going to Europe. He always spent spring in Europe doing film business, visiting friends, visiting his sons. He called her from Spain and reassured her.

"Don't worry. I think they will move it very quickly."

"Yes, I have already received word that my visa is ready."

"Really."

"I only have to go to the embassy to pick it up."

"The consulate."

"Yes, as a matter of fact I am going to New York next week."

"Really?"

"Yes, it seems I have an uncle there, and he is coming down, and he'll take me."

"Well -- that is very -- that's very fast."

Uncle Edner came to Haiti and flew with her to JFK airport, where they displayed their documents, his green card and her new visa. They entered the U.S. with dizzying ease. Then he ushered her into his waiting taxi -- an orange-yellow Chevrolet. It was his. "My medallion," he said, and in time she learned that this was a country where having your own medallion stood for something. It was quickly clear that he, and not her father, was the real power in the family, and the source of this power was the fact that he owned a taxi medallion.

Her father lived in Brooklyn in a small apartment that was dark and rented. Lanuwobi had always heard of this man as Uncle Lionel. Now, after she had fitted together numerous pieces of history, Uncle Lionel, the unknown man who sent money from Brooklyn, was gradually revealed to be her father.

She had always thought of Brooklyn as a wonderful place, a place from which money came. But now she could see that the place called Queens was much better. Uncle Edner lived in Queens, and he took her to his home to live. At first she was uncertain, because although Brooklyn was a disappointment, Edner lived in a place called Jamaica, which sounded as if it would be worse. But Brooklyn was old and dark and Queens was new and low to the ground, which gave it much more daylight. When Palle called, she described Uncle Edner's house as "a large home that he owned himself -- very new and modern and filled with new furniture." It was a new, two-story house in a neighborhood with a great many other new houses. Everything about the houses was clean. The sides of the houses looked like painted wood, but they were smoother and shinier and they washed completely clean when it rained. Edner had explained this to her. Sometimes when it didn't rain, he would spray a hose on the white sides. It was a washable house.

Uncle Edner had a potbelly that pressed so round against his shirt that she was sure if she touched it, it would feel perfectly hard, like a tightly inflated plastic ball. With his thick balding head and the rolls on the back of his neck, he had the kind of tough and well-fed look that in Haiti would have immediately been recognized as a Macoute look. But he was not a Macoute. He had left in the 1960s to escape Papa Doc. Here in Queens you did not have to be a Macoute to get a potbelly.

Edner looked the way Lanuwobi had imagined her father, whereas her father, Uncle Lionel, was a very lean man with a chronically worried face beneath oblique eyebrows. From the beginning, everything about the two uncles seemed to get reversed. Instead of Uncle Edner and her father, Lanuwobi started referring to them as Uncle Lionel and her real uncle.

Her real uncle and her father settled her into Edner's house with no discussion of how long she would be staying. Edner explained to her, "You're in America now. See what you can do with it."

"Do with it?"

"Yes. Everybody gains something from America. What are you going to do?"

Palle would call her in Queens from Europe -- the different capitals -- and would nervously talk about his schedule. How he hoped to get back to Haiti by late June. July at the latest. Something had already changed. Before this, when he went to Europe he offered very little information about when he planned to return. Now he was proposing a schedule for meeting back in Haiti, and she responded with phrases like, "Yes, but it's a problem now." Or, "It is not so easy anymore."

Palle called up Ernesto in Haiti and asked him what he thought these statements meant. Ernesto explained that it was more important than ever to keep the family at a distance.

Palle was beginning to worry that she would not be back in Haiti when he got there. He finally said, "I will be back on June twenty-first." This was unusually blunt. She responded softly in that wonderful voice, "I don't think I can go then."

"Why not? What are you doing in New York?"

"It's just not that easy. You have to get something from being in New York. I haven't gotten anything yet."

"What do you want to get? We can get it."

"I don't know yet."

Ernesto had warned him to save this next line for a desperate moment. It seemed to Palle that this was that moment, and he said it. "Remember, Lanuwobi, I helped you get this visa."

Calmly, in her lovely voice, she replied, "That is not the way they see it."

"Your family? Why don't they see it like that?"

There was no sound at all on the telephone line, and then he heard her say,

"They would never believe that. Never."

"You must tell them. Have you told them?"

"Yes, but they said that was not how I got it at all."

"You must tell them. Explain about my friend Simpson in the consulate and the man from Washington. Tell them."

"Oh."

She did explain it to Edner, but he explained that this was a trick theblanshave. They always say they made a telephone call and made it happen. He told her the story of abokor,a master of Voodoo magic, in Croix des Bouquets. Anytime anyone in the village wanted something, he always said, "I will mix you a powder." If it didn't happen, theloas,the spirits, were against it; if it did happen, he would soon appear and say, "Don't forget, it was I who made the powder."

He was going to lose her. Somehow -- maybe because he had not listened to Ernesto -- somehow he had played it all wrong, and now he was going to lose her. He paced a gray carpet on a gray afternoon in a Paris hotel room. How could he keep her? He had to do something. He sat at the small writing desk.

"Things have gotten far from what I intended -- things are becoming terribly wrong and misunderstood. We must undo everything and get back to what we had. Back to Haiti. We must both go back to Haiti and be together, and this time I realize that you are completely right. Our lives should be together. We should get married there as soon as possible. A big wedding. I love you."

He mailed it and anticipated her excitement in their next phone call. But instead he heard frustration in her voice. "Why don't you see it? It is not so easy now. You should have married me before I went to New York. I told you that."

"I will marry you now. We can go back to Haiti, be like we were and get married."

"Now it is much more complicated. You better come here."

He was the director, and now this film was drifting out of his control, or as he put it in his peculiar linguistic blend, "The story is escaping mymise-en-scène.I can't bear that." But he was in production for two films, and he was not able to take even one week off from March until the end of October. Self-torture became his mental pastime. He imagined her meeting someone else. Someone who was still older than she but a little younger than he was, or someone who was really rich, someone who had the ability to spend money with truly dazzling abandon. He imagined her falling in love with New York. He had heard of such things happening. People sometimes fall in love with places even when they are awful. He understood this. He had even done films with this idea.

This was not the way life was supposed to be. He wasn't supposed to be imagining all of these unpleasant scenarios. He was supposed to know what would happen next. He was the director.

He called her as often as he could. He sent her letters so that she would understand that their relationship was something solid -- that she could count on it. He told her how much he loved her, how good his intentions were. In his interviews with the Danish press he always mentioned her in ways that made them seem very much a couple, and he would clip these articles and mail them to her. All of Denmark knew that he and Lanuwobi were together. But he was not sure.

This was a very long and dangerous period of absence. He must do something -- something radical.

He telephoned her with the news. He had decided that she should go to Denmark. She should join him for the summer in Denmark.

"I don't think they will let me."

"Who?"

"Things are more complicated now. If we had been married in Haiti, this wouldn't be a problem now. But we didn't. Now you must talk to my uncle."

"Your uncle?"

"Yes, my real uncle. We can work out a time to call. Then you call. I will tell you what to say."

"And what am I supposed to say?"

"First you have to say that you intend to marry me."

"Yes, that's all right."

"If he asks if you have been married before, tell the truth."

"All right."

"But not all of it."

"Which part?"

"You can say that you were married once and then divorced. But don't say that you have been divorced three times. And don't tell him that you are fifty-six years old!"

"How old should I be?"

"Fifty. Only fifty. And you have three children but not four. Four is too much. And these are all things that you should not mention at all. But if you are asked, then say you are fifty, divorced once, and three children. This is important. Don't forget to say you were divorced."

"It seems complicated."

"It is complicated. That is your fault!"

But she said all this in her lovely voice. He still thought she had the most extraordinary telephone voice -- husky and rich like the soft middle range of a cello. And her English was very good now. She had him to thank for that.

He called the uncle at the appointed time. To his irritation, Palle noticed that he felt very nervous about this telephone call. Here he was, fifty-six years old, or fifty, whatever it was, an international filmmaker, and now he was getting little flips in the center of his stomach because he had to call his girlfriend's uncle and ask to take her on a trip. He had to call this man he had never seen. In Queens. A taxi driver in Queens. He tried to picture the uncle in his house with his new furniture, this taxi driver in his modern palace.

He telephoned from his hotel room in the sixth arrondissement of Paris. He told Edner who he was and even described his last three films. Edner interrupted to ask, "How old are you?"

"I am fifty years old," said Palle flawlessly. And then he could not resist asking, "How old are you?" Edner didn't answer. It was a mistake. Palle knew it would be, but he couldn't resist. It was just a small one. The rest of the conversation seemed to go well. He told Edner that he loved Lanuwobi. Well, not "loved," but "cared for," and wanted her to join him in Europe.

"That is absolutely impossible," said the unknown taxi driver in Queens. Palle noticed that Edner also had a very nice telephone voice. "We do not do things this way in our family. You may marry her. That is for you and her to decide." Then his tone of voice changed, became a little tighter in the throat. "After you are married, you decide, not her. You understand, yes?"

"Yes, I understand," said Palle.

"I am not against your getting married. We can talk about it when you come to New York. We can make plans. But going to Denmark now is out of the question. We don't do things like that."

"You realize of course that Lanuwobi and I, we -- we know each other well. We stayed with each other in Haiti. I mean..."

"I don't want to hear about this. I never agreed with her mother about this. We will talk more when you come," Edner said warmly. It was an invitation.

Finally, in October Palle flew to New York. Everything was to be done in the proper way. Palle would stay at a Manhattan hotel, and Lanuwobi would stay out in Queens, and they would not spend their nights together.

Lanuwobi met him at JFK airport. She was with her sister, who was plumper and had neither the powerful black eyes nor the soft voice. She also had a more direct manner, and Palle could tell that she had spent more time in New York than Lanuwobi had. The three of them rode together in a taxi to Manhattan and up the elevator to the third floor of the Gramercy Park Hotel, to the moss-green suite where he stayed in New York. Lanuwobi and her sister padded over the spongy green carpet and tried out the green upholstered furniture and examined the view of Lexington Avenue while Palle sat on the edge of his queen-size bed and realized that the sister was a chaperon. In late afternoon, the two sisters left together for Queens.

The next day, they managed to get a few hours alone at the Gramercy Park, hours spent wrapped together in the roomy bed. Then she got dressed and left. And it remained that way. No evenings. No nights. Always just a few hours during the day. Wonderful little moments, but not enough. Events were inexorably drifting toward what Palle referred to as "a rendezvous in Queens."

Lanuwobi prepared him, cautioning, "You must wear a very nice suit. It must be very good quality. And you must have a tie." After consulting by telephone with Ernesto, Palle bought Belgian chocolates at Bloomingdale's and an enormous bouquet of purple irises and white lilies, and he put on a slate gray Gianni Versace suit and a gray-and-purple Giorgio Armani tie and struggled to slip, lilies and all, into the backseat of a taxi and was nervously on his way to Queens. Somehow at age fifty-six he was the boyish suitor he never had been called upon to be in his youth.

Palle and the taxi driver could not locate Edner's address. Many of the houses were new and a number of people looked Haitian, so it seemed to be the right neighborhood, but Palle was confused by the similarity of all the streets. "It's very amorphous out here," Palle told the taxi driver, who did not respond but rolled down his window and started making inquiries in Creole.

They found the house because they saw Lanuwobi and her father waiting on the curb. By then the taxi meter was up to fifty dollars. Lanuwobi wore a new silk dress, a coral color that set off her darkness. Standing a little back in the doorway to the house was potbellied Uncle Edner, the real uncle, looking so confident and gracious, so marvelously in charge that for an awkward moment Palle could not decide to whom he should hand the flowers. He was warmly ushered into the living room, which was, as Lanuwobi had foretold, very new. The walls were a new wooden paneling that it took Palle only half a second to detect as fake, and all the furniture was covered in a heavy, shiny clear plastic. Everything was plastic, even the white siding on the house. Palle had never seen so much plastic.

He was ushered to a red couch, which made unpleasant noises when he sank into it. The plastic was very slippery against the silk-linen blend of his Versace suit. He felt as if he could slide right off if he did not sit carefully upright. He was handed a glass of wine in a small glass with an elaborately shaped stem and ornate designs etched on the bowl. He thought this a very ugly glass. The wine was very sweet.

Edner and the father sat on plastic-covered chairs very close to Palle. The women -- Edner's wife, their daughters, Lanuwobi's sister -- distanced themselves toward the outer edge of the room. Lanuwobi had told him of how Edner's daughter had become a banker and how both girls had graduate degrees and even the mother had gone to university. But Palle never talked to them. They remained in the distance and they did not speak.

Palle asserted that he intended to marry Lanuwobi. He knew he had to sell his case, and he looked with great sincerity into Edner's eyes and said, "I love your daughter, and I want to take care of her" -- in the distant edge of the room he could hear women giggling -- "and...and make her happy." Then he remembered that Lanuwobi was not Edner's daughter, and he shifted his weight cautiously on the slippery plastic and looked into the father's worried eyes. "You know," Palle said, "I am quite a respected man in my country. You can verify this. I can give you a number to call at the Danish Embassy in Washington, and they will tell you -- You can talk to the ambassador himself. He knows me. He will speak well of me."

Inside, Palle was laughing at the spectacle of himself pleading his respectability. Lanuwobi found a moment to throw her arms around him in the hallway and plant a secret kiss on his lips and say, "You are fantastic! They love this. And you look wonderful in this suit!"

Going back into the living room, he saw a look from one of Edner's daughters that made it clear she had seen the kiss.

In the end, Uncle Edner said, "You can marry her. This would be fine. And then you make the decisions, not her, you decide everything. You understand?"

"Yes, certainly," said Palle.

The worried father nodded eagerly.

"Yes, you will decide everything. But, of course until you are married, things must be done, you know,comme il faut.You understand?"

"Yes. I understand, but of course while I am here, I stay in a hotel in Manhattan -- "

Edner held up a finger to silence him. He smiled generously and showed large teeth. "This is not how we do it in this family." It was clear that he would not discuss this subject anymore. Palle looked at the father. The father was nodding sternly.

"You are always welcome here to visit Lanuwobi," said Edner, standing up to dismiss Palle. "And let us know about the wedding plans."

"Yes, and then I will decide," Palle offered, trying to be agreeable.

"Then you decide everything," said Edner warmly, and he laid a thick hand on Palle's shoulder. Lionel followed with a light pat and a nod. Edner offered him a ride back to Manhattan in his taxi, which Palle was grateful for, not wanting to spend another fifty dollars. Before they left, Lanuwobi looked at Palle admiringly and told him how fantastic he was. The taxi had the same clear plastic seat coverings. On the way, Edner asked to see a copy of his divorce decree, and Palle promised to produce one, though he was not exactly sure of where to get a copy. After saying good-bye to Edner at the shady foot of Lexington Avenue, he had an odd sense of freedom, as though he had gotten back the right to his own identity. The fine cloth of his suit felt good against his legs. He chuckled a little with a thought, "They probably never even heard of Gianni Versace."

Palle and Lanuwobi did not see each other often in New York. He did not like going out to the house in Queens, and for her Manhattan was almost an hour away on the E train -- an unkind underground world where people had their own music plugged directly into their ears. They hummed and tapped and swayed to hissing noises she could only guess at, and they never looked into anyone's eyes.

But sometimes Palle and Lanuwobi would have wonderful two-hour afternoons in the Gramercy Park Hotel. He could not remember any other woman making him feel quite so good, so powerful -- then he would remember that he could lose her.

"Lanuwobi," he said, holding her, softly inhaling her from behind her ear. "We must undo all of this. Back to Haiti. I'll still marry you. Undo all of this. This is not what I thought."

"I told you back in Port-au-Prince you should have married me. That would have been simple," she said with reproach in her voice. Why had he put her in this impossible situation? she wanted to know.

Palle consulted Ernesto and was told that the next step was to become engaged.

"How do I do that?" Palle asked.

"You must buy a ring, " said Ernesto.

"A ring? What kind of ring?"

"An engagement ring, you fool."

Palle had not bought an engagement ring for any of his three wives. He had bought a wedding ring for his first wife but never an engagement ring. So on his next visit to Copenhagen he called on a friend, a well known sculptress who had exquisite taste, and they went to a goldsmith and had a ring designed -- a simple gold band shooting off at a sharp angle toward three small tasteful diamonds. On his next trip to New York, while walking in the shade of Gramercy Park kicking leaves, he presented the ring with appropriate understated theatricality. But she did not open the box.

"What's wrong, Lanuwobi? This is an engagement ring."

"This is not how you give an engagement ring."

"This is fantastic! I never heard these things. How do you give an engagement ring?"

"You create an occasion. Then you give it."

Palle was not angry. When he used the English word "fantastic," he meant it literally, out of fantasy. He loved his life, that he could leave his Nordic world with its simple rules and become enmeshed in a society so complicated that no one could possibly master all its rules. "All right, I will create an occasion," he said agreeably.

But he did not really get to create it. He informed her family, and they arranged it at a family friend's apartment in Brooklyn. Palle, once again, was in a taxi with an enormous bouquet of flowers and once again could not find the building. Somewhere in Flatbush. The Chinese taxi driver was frightened. "Mister, mister," he cried each time Palle said, "Try this street here."

"Dark street. No good! Neighborhood no good." Palle decided he was right, and when they found the building, he paid the driver an extra ten dollars to wait while he made sure it was the right place.

When he entered the apartment, he was overwhelmed by a sense of being in the kind of surreal film he had studied but never made. He reported to Ernesto with awe in his voice, "The apartment was filled with strange objects from a taste beyond our horizons -- strange strange glass things and cupboards with all kinds of porcelain."

Everything was large except the apartment itself. One room was almost entirely filled with a massive mahogany table. There were tall vases stuffed with enormous plastic flowers. On the walls were paintings in gold and linen frames of what might have been Paris except the colors were too bright. There were elaborate crystal pieces of no discernable function and chandeliers that perpetually tinkled like wind chimes because the ceilings were too low and there was always someone who had just brushed by. The Haitian woman whose home it was had an enormous, stiff hairdo, like the brittle nest of a large raptor, and could not get past the chandeliers even when she ducked. Her makeup was thick and almost stylized, and her eyes were painted into a shape unknown to nature. Her soft, fleshy arms, skin puffed and tucked like the limbs of babies, were decorated with dozens of bracelets. Even the buttons on her dress contained jewels. The entire home seemed like a huge, overdecorated cake. They sat around a gold-and-glass coffee table and sipped sweet drinks and then ate a dinner ofbanane, griots,and rice and peas -- enormous porcelain bowls of everything devoured with the frenzy of the starving.

Then it was time for Palle's speech. Plump, well-fed faces, shiny and a little overheated from having eaten so hard, stared up at him. It was the presentation of the ring. Palle declared his love, which produced no particular reaction, and then his intention to take care of her and make her happy. The faces nodded. Then he took out the ring, and they strained around the table to get a better look. He heard one woman say"trois"approvingly because there were three diamonds, but the woman next to her responded with a shrug because they were not particularly large diamonds. Palle expected one of them to put a small scale on the table. But then, they seemed to know their stones, could probably measure without scales. He could see that Lanuwobi was not pleased by the ring. He later asked her about it.

"Well, it is very modern," she said.

"I thought you liked modern. You are always telling me that you like your uncle's house because it is modern."

"I like the ring," she said unconvincingly, and kissed him.

Palle wanted to keep the wedding, his fourth marriage, discreet and, if possible, out of the Danish papers. The Danish Consulate recommended a Danish minister at a church for Danish sailors on an affluent street in Brooklyn Heights. It was a pretty little church with only forty seats. Palle was pleased by the size. He had told Lanuwobi that he wanted a small wedding. "Only yourclosestrelatives. Not all these people from Miami and wherever."

The minister was a young man, with great enthusiasm and crisp, open, Nordic manners. It was like being in Denmark. He invited them into a little room for coffee and cake. Lanuwobi was charmed by this coffee-and-cake ritual, but she thought this priest seemed so young and happy and informal and not at all the way a priest should be. The minister examined the divorce decree that Palle's son had mailed him from archives in Copenhagen and declared it "in good order." There was no need for a translation, which Edner had asked for, nor was there any blood test requirement as Edner had insisted. The requirement had been dropped in New York. They had only to set a date.

Palle, who had forgotten Danish ways, was not prepared for this. He had grown accustomed to complications. He started to become nervous. He had to do some filming in Haiti. The date would be after that. He would come back for the wedding. It would be in several months. After the shooting.

He never made it back for the wedding date. His mother died in Denmark, and he had to spend time in Copenhagen with his octogenarian father. Lanuwobi and Edner understood. This was a family matter. Palle had invested time, and he had forged an understanding with the family in Queens.

Palle would have felt less confident if he had ever seen one of the family meetings that Edner hosted every Sunday. Lanuwobi was placed on the plastic-covered couch, with her father staring mournfully at her from one stuffed chair and Edner imperiously from the other. Another uncle seemed to come over for the purpose of drinking beer, and he stood by the doorway to the kitchen to be as close as possible to the source. The women took their places on the outer edge of the room. It was very different from when Palle was there. Now the women weren't giggling. They were gazing sternly at Lanuwobi with their chins held high, so that they were clearly looking down.

"You will marry this white man and he will take you back to Haiti?" said Edner "He must be insane. Back to Haiti. What kind of offer is this? What is he promising?"

"He wants to marry me," Lanuwobi said unpersuasively.

"But what is he offering?" Edner wanted to know. "Does he own a home in Haiti?"

"He stays in a hotel."

The room filled with clicking tongues and "oh-oh's."

"So where does he own a home?" asked the father in a soft voice that still had an impact because he so rarely asked anything.

"I don't really -- I'm not sure he does own a home."

"Anywhere?" said Edner, his eyes enlarged with astonishment. The room fell silent -- a spell only broken by the hiss of a beer bottle being popped open by the uncle in the kitchen.

"What kind of car does he have?" Edner's wife challenged. The men stiffened and Edner glared but refused to look in his wife's direction.

Lanuwobi, with tears of shame giving a shine to her large eyes, had to admit that he rented his car also.

"I don't like the divorce certificate," the father announced. "I don't like it at all. What kind of language is it written in?"

"It's his language. It's Danish," Lanuwobi tried to explain.

Edner's round face turned to a kind smile. "Yes. It is written in Danish." Then he brought his large cantaloupe-shaped head very close to Lanuwobi and, still smiling, whispered, "How do we know what it says?"

"The priest is Danish too. He could read it. He said it was good."

Giggles exploded in tiny bursts around the outside of the room. Edner explained, "Lanuwobi, this is the way theblansare. He finds this priest. We don't know where. He just finds him. And by co-in-ci-dence" -- he pronounced the word carefully, and not only the women but her father all responded with big, toothy, spitting laughter -- "by coincidence, he turns out to be Danish too? And then he tells us that the certificate is good. Who is this priest?"

"Is he Catholic?" Edner's wife asked. This time Edner turned to make sure his wife received the glare.

"Lanuwobi," Edner said, turning back to her with a gentle voice, "don't you see that they are working together? That is the way theblansdo things. What does he offer your children, this man with the secret language who owns nothing? What is there in Haiti for the children of people who own nothing? You have to stay in New York. You can get an education. You can earn money. Buy a home."

"Lanuwobi," said her father, "if you go back to Haiti, I will not be your father anymore." As he was saying this, Lanuwobi saw her sister in the back of the room, arms crossed, rolling her eyes upward contemptuously. Her sister did not like Lionel and always said that he had no right to call himself their father after all this time. But Lanuwobi liked having a father.

When Palle returned to New York, Lanuwobi reported all this to him. Now Palle understood. The minute he leaves, this is how they talk. This is why Haitian negotiations always break down. It was a mistake to negotiate at all. He could see that now. "I don't want to go out there anymore. You have to deal with them. I am not doing that anymore. I made the effort. I presented myself properly. Now that phase is over. Now we are on to a new phase."

"But what can I do?" Lanuwobi pleaded. "If I do something against them, they will never see me again."

"Against them?"

"Yes, if I go with you to Haiti against their wishes, then it is over. I will not have my family. They will never talk to me again." She stared hard into Palle's pale eyes. "What can I do?"

Palle, who always offered her solutions, said, "I want you to come with me. That is as simple as that."

"If I do that, I can never go back to them. And if you are not there anymore, if you die or leave me, where will I be? I will be in Haiti, left by a white man, with no family in America anymore. What security do I have?Qu'est ce que je tire de toute ça?What will I get from this? I started with nothing. I can't end up that way. I have to get something."

Palle understood. This was not a European conversation. It was part of the charm of their relationship. He did not want a European relationship. She expected something, and he could provide something. They each had their roles. That was why Ernesto thought prenuptial agreements were important. "Work out a solid contract," he often told Palle.

She never asked him for money, but they always talked a little bit about it. Edner had arranged for her to train as a nurse, and she was making a modest salary as a nurse's aide. Edner told her to be patient. "Soon you will be a full nurse. You can meet other Haitian nurses and start a fund. Before long you can buy a home. You can have things in this country. I didn't arrive here with a medallion, you know?"

But for the time being, her salary was very low, and Palle gave her money to help her. Whenever he offered the money, she took it. There was never a discussion. It was something she got. He would give her one hundred or two hundred dollars. Once, after not seeing her for a long time, he gave her five hundred dollars and told her to go shopping.

The problem was more complicated than a few hundred dollars. If she went back to Haiti for a visit, she would have to bring presents for her mother, her brother, other people. Good, expensive, American presents.

He could help her with that.

But if she went back to Haiti to live, she would have to bring something permanent with her -- a diploma, a marriage to a wealthy man, something she had gotten in America. To go to America and come back no more of a person than when you left would be -- it was unthinkable.

She wanted Palle to pay for her education in New York.

"Well, Lanuwobi," he said. "Education is very expensive in America, and I am not a rich man." This statement was a mistake because it meant that if she went back to Haiti, she would be returning with neither an education nor a wealthy marriage. But then he said something that not only made more sense to her but was much more honest. He said, "Besides, if I pay for your education, what do I get out of it?"

She nodded in agreement. He was beginning to understand. "There is another problem. Remember the five hundred dollars you gave me for shopping last time?"

"Yes."

"Well, I didn't shop with most of it. I sent it to my family. I do that sometimes when I can. And this is another problem."

"I don't see the problem," Palle said.

"You see, if I go with you to Haiti, I cannot send money from New York."

"Now, that's true. I can see that," he said, failing to repress an ironic smile. "You cannot send money from New York if you are in Haiti. What kind of money did you send to your mother?"

"I send forty dollars to my mother. Twenty dollars to one aunt and twenty dollars to another. Most months."

"That's not so bad. I could help you with that in Haiti."

She nodded. A problem solved. Although she knew that giving it in Haiti would not be the same, would not be as good, as sending it from New York, this was a workable solution. Both of them felt that a point had been won.

"And you know the beauty salon is still possible. Of course not right now. The embargo and no electricity. It is not the right time to start a business there. But later I think it could be a very good thing."

"Yes, I would like that, but -- "

"But, what?" Another obstacle. He would have a solution. "What?"

"If I start a beauty salon in Haiti, I want to have an American diploma in beauty care."

"I see. Well, find out what it costs, for God's sake, find out. Maybe I could...But you know, I am not a wealthy man and I have obligations. I have kids in Europe, and I am still paying, and..."

"I know. You see, if you did not have all these obligations, I would not have hesitated one moment."

Palle understood this. And he understood that she was troubled by the fact that he seemed to have nothing. These were real concerns, and he would have to work on being more of a man of substance. He would have to offer her a life worthy of her return.

And then it landed as though fallen from a tree.

When he returned to Haiti, he learned from Ernesto that the Whitcomb House had become available. Whitcomb was leaving and wanted to rent his gingerbread mansion complete with staff, furnishings, and the art collection. With gun battles every night, an embargo by most of the world, and rumors of invasion, it was not expensive. Whitcomb just wanted someone to take care of his property. Ernesto made the introduction, and the lease was worked out. With great excitement Palle called Lanuwobi.

"Lanuwobi, I have just rented the most beautiful house in Haiti, the Whitcomb House. Have you heard of it?"

She had.

"It is huge, the most beautiful house in the country, and with servants to do everything. You can be like a queen here, an absolute queen! Come here. The staff will take care of everything. There is everything that you like. You will be taken care of. Waited on. You will beMadame!"

"Yes, it sounds like it would be all right."

"All right? Just all right!"

"But you don't own it."

"No," he said quietly.

"And that is exactly what my family would say. You don't own it."

"No, and I don't want to own it! This is perfect for me. It is my ultimate ambition to live in this house, do you understand? It is like a dream. I don't want anything else. I don't want to trade it in for a small house that I own."

"Well, a large house is nice. We will have to buy a lot of furniture."

"It comes with the house!"

"It is entirely full."

"It is perfect. Very nice furniture."

"But if the house is already full of furniture, it means that you can't buy furniture for your home."

"No. The furniture that is here is perfect. There is no need to buy furniture."

Palle did not despair. He had to leave for Europe soon, and when he came back in the fall, she would come with him to his rented mansion. It was a better life than her family could offer her in Queens. The cards were all moving back to his side of the table. He could see that she was growing tired of New York and her family in New York, and she missed her mother. She didn't like her nursing job and not having enough money to pay for an education. By next fall, she would be through with New York. Here they could play the game of living like the rich without any money.

"I think I can offer you a more interesting life, Lanuwobi. You come down to Haiti. I am not going to marry you in New York. I'm through with that now. You come here. I will show you a good life. Then we can get married."

Palle recognized that he was not a young man ruled by passions. He would make this work, or he would give her up. He did not have to get this woman. He was at an age when he looked at these things more philosophically. If she decided to stay in New York -- which he doubted she would -- he was content with the idea that he had experienced this, he had had pleasure with her and he had helped her, helped her in many ways. He could always feel good about that, even if she went on to a different life.

At last, Palle felt in control again.

In Copenhagen, his oldest son was supportive of whatever he wanted to do, but his second son, a law student, had confided in Palle's ex-wife that he suspected his father was being manipulated by Voodoo.

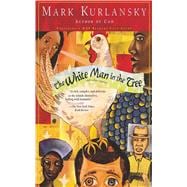

Copyright © 2000 by Mark Kurlansky