|

1 | (64) | |||

|

65 | (22) | |||

|

87 | (26) | |||

|

113 | (10) | |||

|

123 | (34) | |||

|

157 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

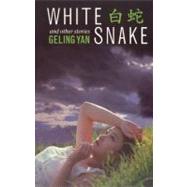

White Snake

TRANSLATOR'S PROLOGUE: This story is set mostly in the "ten years of chaos" of China's Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-76), when the social order turned upside down and traditional arts were brutally suppressed in favor of "revolutionary" models.

Essential to understanding this story is a basic knowledge of the legend of White Snake, which is the basis of a Chinese opera. In this novella, the main character, Sun Likun, develops the White Snake story into her signature ballet.

The legend of White Snake concerns twonagas, or mythical serpents, White Snake (a female) and Blue Snake (a male), who had attained the status of Immortals and lived in the heavens. Blue Snake fell in love with White Snake and asked her to marry him. White Snake made Blue Snake a wager: they would fight a battle, and if Blue Snake won, White Snake would become his consort, but if White Snake won, then Blue Snake would turn into a female and become White Snake's maidservant. Deeply enamored of White Snake and desiring to be with her at all costs, Blue Snake accepted the challenge. White Snake won the battle, and Blue Snake became her handmaiden.

One day the pair descended to earth. They took human form as two beautiful young women, Lady White and Lady Blue, and set up residence in Hangzhou. While taking a ferry at Broken Bridge, White Snake met and fell in love with a young scholar named Xu Xian( pronounced "shyü"). They married and started a medicine shop in a town along the Yangtze River, and White Snake used her magical powers to render Xu Xian's medicines especially effective, affording them a prosperous life.

A Buddhist abbot named Fa Hai saw through her disguise and warned Xu Xian that his wife was actually a snake. He gave Xu Xian a potion to give his wife to drink which would return her to her original serpent form. Xu Xian gave her this potion and, when he gazed on her original form, promptly died of fright. White Snake then went through a great odyssey to obtain the potentlingzhi fungus to restore her husband to life.

The revived Xu Xian remained fearful of his wife and fled to the abbot's monastery for refuge. White Snake came to plead with the abbot, but to no avail. In anger, she attacked the monastery with a great horde of underwater creatures.

The battle was a draw, and the abbot came to realize that he had failed to best her because White Snake was pregnant. He advised Xu Xian to return and live with her until the child was born. Upon his return, Blue Snake almost killed Xu Xian with her sword, but White Snake intervened.

The child was born, and Fa Hai conspired with Xu Xian to have White Snake resume her original form and be imprisoned under Thunder Peak Pagoda at West Lake in Hangzhou. They succeeded in this plan, but later Blue Snake came and destroyed the pagoda and rescued White Snake. The two departed the world of mortals and re-ascended into the heavens. (This synopsis is adapted fromPeking Opera and Mei Lanfang, New World Press, Beijing, 1980.)

THE OFFICIAL ACCOUNT, Part 1

A Letter to Premier Zhou Enlai

Respected and beloved Premier!

First, please allow us to express our collective wishes for long life without end for our Great Leader Chairman Mao!

All of Sichuan Province's eighty million people were deeply moved that our Premier, in the midst of so many important and pressing matters, recently found the time to request that his personal secretary call and inquire about the state of health of the formerly famous dancer Sun Likun. This very clearly shows that our Premier, occupied as he is with myriad affairs of state and heavily burdened day and night with the work of the Revolution and the construction of our Socialist Motherland, still constantly takes to heart the sufferings of the people. Though our province's propaganda, culture and education authorities were not directly involved in the case of Sun Likun, subsequent to receiving your personal secretary's telephone call, and acting in accordance with the Premier's intention to protect our country's important talents, we sent a special emissary to the provincial Performing Arts Troupe to investigate Sun Likun's incarceration, interrogation and sentencing up to the time when she suffered a mental breakdown. The results of this investigation are as follows:

Sun Likun, female, presently 34 years of age, was formerly a major performer in the Sichuan Province Performing Arts Troupe. In 1958 and 1959, she traveled to the Soviet Union's International Song and Dance Festival, where she won the Stalin Prize for the Arts. In 1962 she received First Prize in the Solo Ballet Performance category in the All-China National Dance Competition. In 1963, Beijing Film Studios made a film based on The Legend of White Snake , a ballet she both choreographed and performed in. At the same time, the stage version of the ballet played in seventeen cities, causing quite a sensation. In order to study and imitate the behavior of snakes, Sun had apprenticed herself to an Indian snake charmer and had helped him raise snakes. The "snake step," which she developed on her own, became her signature movement, and its performance received tremendous acclaim among ballet critics. The step even became a fad among members of the audience.

In 1966, Sun Likun was denounced by the Revolutionary Masses. In 1969, on the basis of various investigations and Sun's own four-hundred-plus-page self-criticism, Sun was classified as a decadent bourgeois element, a suspected Soviet-trained spy, a seductress and a counter-revolutionary snake-in-the-grass. She was officially placed under investigative detention. Because Sun's place of detention was the scenery warehouse of the provincial Performing Arts Troupe in Chengdu, her living conditions were not overly harsh.

From 1969 onward, Sun's case was reexamined many times, but at no point did the Revolutionary Vigilance Committee exhibit any violence toward her. As for depriving Sun of her personal freedoms, this measure was taken by acclamation of the Revolutionary Masses subsequent to our country's self-defensive counterattack at the Sino-Soviet border. As is the nature of a mass political movement, matters went beyond the control of the leadership, resulting at times in extreme situations.

According to revelations of people close to the Sun Likun case, Sun's mental illness began in December of 1971. In the period prior to this, her guards often saw a young man in his twenties enter Sun Likun's detention room. He carried a letter of introduction from the Exceptional Cases Group of the Central Propaganda Ministry and referred to himself as a special envoy from the Central Government with the assignment of investigating Sun's case. This young man, who wore a woolen military uniform, displayed an aggressive bullying demeanor and gave the overall impression of being well connected. For the duration of one month, this person entered Sun Likun's cell every day promptly at 3:00 PM and left just as punctually at 5:00 PM According to the statements of the guard staff, Sun showed no trace of abnormality during this period. The young man was calm, polite and correct in his behavior, and her morale actually showed improvement. In fact, she was even heard practicing dance exercises late at night in the dark.

It is reported that on a particular day the young man appeared driving a motorcycle with a side car and demanded to take Sun Likun to a certain provincial government guesthouse to proceed further with their discussions. He refused to reveal the purpose of these discussions, intimating that even the highest levels of the provincial leadership did not have the authority to inquire into his handling of this case. Because of the apparently indisputable authority of his letter of introduction and his identifying documents, the Revolutionary Committee agreed to release Sun Likun to his custody, for a period not to exceed six hours. At 10:00 PM sharp, the young man returned Sun Likun to her place of detention. A few days later, Sun Likun suddenly began showing signs of mental illness, talking to herself and alternately crying and laughing.

The young man disappeared from the scene. On the eve of Chinese New Year, Sun was transferred to the Psychiatric Division of the People's Hospital of Sichuan Province. The following week, Sun was moved to Joyous Song Mountain Hospital in Chongqing, our province's most highly respected research institution for mental illness. Sun responded to treatment and gradually stabilized. According to our investigation of hospital personnel, a young man came once and asked to see Sun Likun, but Sun refused to see him. We are currently conducting a systematic investigation to determine whether this was the same young man who had been reviewing her case and further to determine what caused Sun Likun's illness.

We will soon submit a report to the Premier on Sun Likun's state of health. Until then, we respectfully wish to reassure the Premier that there is no cause for concern.

In conclusion, on behalf of the eighty million people of Sichuan Province, we extend to our beloved and respected Premier our most worshipful revolutionary salute! We hope that our Premier will take the utmost care of himself for the sake of all the people of our country and the great undertaking of establishing Communism. For the sake of China's Revolution and the world's, please take care!

(signed)

Sichuan Province Revolutionary Committee

Propaganda, Culture and Education Department

March 31, 1972

(DOCUMENT CLASSIFIED FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY--DOCUMENT CONTROL NO. 00710016)

THE POPULAR ACCOUNT, Part 1

Actually, that formerly famous Sun Likun is a major international slut. Once she had a Russian-language translator help her write a letter to her Soviet paramour telling him that "the flower of our love will forever be in bloom and never wither." Though he and she were "at opposite edges of the sky," she continued, they were "yet closer than neighbors." Later, that same translator copied her letters onto big-character posters and posted them next to the sidewalk of a busy street.

During the years she was performing The Legend of White Snake , Sun Likun toured seventeen cities, both large and small, and in every city there were men chasing after her. That water snake waist of hers got the men coiled up in her bed in no time. All the men who slept with Sun Likun said she had 120 vertebrae. She could twist any way she felt like twisting. There wasn't a straight bone in her body. She could wind back and forth at will, so the effect was as if she had no bones at all.

Actually, she only looked tall. She seemed to grow two inches taller every time she raised that pointy chin of hers -- and she always kept it raised, even when the masses would harangue her in struggle sessions. Her beauty was in her chin and neck. As she turned her face this way and rotated it that way, her gaze fell on no one. If ten thousand people came to her struggle session, eight thousand were there for the sole purpose of seeing her snakelike neck. Of the ten thousand, nine thousand would have seen her in The Legend of White Snake at least three times. People in Sichuan used to say our province had three famous products: pickled mustard roots, five-grain spirits and Sun Likun.

After Sun Likun got fat, she became an ordinary woman. Less than six months of being locked up in the Performing Arts Troupe's scenery warehouse and she looked exactly like any middle-aged woman you'd see on the street: a keg-shaped waist, gourdlike breasts, and big squarish buttocks that spread out so wide you could lay out a whole meal on them. Her face was still pretty, only broader, and her eyelashes would still sweep back and forth until you felt your heart tickle, but the black and the white of her eyes were starting to lose their clarity.

The scenery warehouse of the Performing Arts Troupe was on the second floor. Down below, the building was encircled by a wall. If you stood on the wall, you were at eye level with Sun Likun's bed. Under the bed, instead of her famous brightly colored pet snake, was a brightly colored chamber pot. Beyond the wall was a messy construction site. A building had been torn down and a new one had yet to be built, so the ground was strewn with worn-out tiles and stacks of new bricks.

On the site some idle construction workers were playing a card game on an improvised table made of bricks. They were singing:

I've seen thousands of pretty girls

But you are the prettiest in the world:

Ears like scoops, persimmon-cake face,

Green bean eyes and skinny chicken legs.

Sun Likun knew they were singing to her, trying to tease her into cheerfulness. She had been locked in there for two years already, and she was only allowed to leave the room to take a shit. First, she had to ask for permission from a guard; only if she received it could she go out the door leading down the hall to the latrine. When she needed to pee, she would do it in her chamberpot, and every night, with permission, she carried this colorful pot down the hall to dump its contents. The distance from here to there was only about ten paces, but all the while the guard would follow behind her with a big club. The Vigilance Committee guards were all teenage girls, dance students at the Performing Arts Academy. In keeping with the revolutionary operas of the last few years, they all had broad shoulders, thick legs and loud voices. Boys from the Academy weren't allowed to serve on Sun Likun's Vigilance Committee; they would have ended up serving under the vigilance of Sun Likun. The teenage girl dancers had worshipped Sun Likun. Whenever they would enter her dressing room or her private exercise room, where she'd hung the picture of herself with Premier Zhou Enlai, they would do so with the awe of one entering an ancestral shrine. Because such reverence easily turns to resentment, the girls made utterly reliable club-wielding wardens for "Ancestor" Sun Likun.

The bathroom Sun Likun used had only one working squat toilet -- the other squat toilets didn't flush properly. The sole functioning toilet was directly in line with the doorway, but the girl guards did not permit Sun Likun to close the door when she squatted there. She would sit facing the young guard who formed an X across the doorway, a club dangling across her stocky thigh. In the beginning of her internment, eye-to-eye in this manner, she could squat for an hour with no results. She would beg the girls to avert their eyes. Crying real tears, she would plead, "if you don't turn your eyes away, I won't be able to do anything, even if I die of misery." But the guards absolutely would not soften their hearts. You used to be so elegant, they thought, like a celestial being. You never seemed to eat the same food or breathe the same air or shit the same shit as everyone else. Now you're just one of us ordinary folks, squatting on the latrine like millions of your fellow countrymen.

By the summer of 1970, Sun Likun had finally learned how to have a bowel movement while squatting face-to-face with one of the teenage girls. She could squat comfortably on the toilet and would spit on the floor while she waited, just like all the rest of the Chinese masses. Sun Likun had become accustomed to her ignominy. She no longer felt as if she would die of shame whenever she was called a string of nasty names.

The same crew of construction workers was still down below, singing songs and playing cards. Every once in a while they would have a political study session or lackadaisically lay a few bricks. At night they would spread out a picnic on the platform of bricks, drink seventy-cents-a-bottle orange wine and heed the wine's call to arms, shouting guess-finger drinking songs with verses like, "your mama slept with eight men, eight men."

One morning they noticed that the shutters of the upper room were open. No longer would they need to climb up to the top of the wall and peer through cracks in the shutters to catch a glimpse of that beautiful fat snake-woman. Because this day--and every day after--she appeared to them of her own will, without any self-consciousness.

The damsel in the window was as white as a spring silkworm ready to spit its silk. As she stood there--this "famous product" of Sichuan--all the construction workers, young and old, seemed frightened to see her up close for the first time. Their singing stopped. Suddenly self-conscious, the bricklayers started laying bricks and the mortar mixers started mixing mortar.

Sun Likun brushed her teeth at this window every morning. The toothbrush had very few bristles left, and the rasping it made in her mouth sounded painful. By now the workers had dared to look her in the face and smile at her openly, the old men flashing yellow teeth and the young men white. While they looked at her, they would holler, "D'ya see that? Look how white her arms are, like steamed pork buns!" They still didn't dare speak to her directly. She had been up in the heavens for so many years while they had been here below that, even though they could now look upon her face, they weren't entirely sure they now shared the world of mortals with her.

Sun Likun could hear them discussing her right below the window, arguing about all sorts of rumors surrounding her, just as if she were a painting. However they spoke about her, good or ill, there was no restraining them. Their arguments grew heated. One said, "She lived together with a snake, that's what they wrote on the big-character posters. It was a big bright-colored python. The snake slept under the bed, and she slept up on top of the bed." Another one objected, "It was a white python! A white python!" They argued back and forth, "White python!" "Bright-colored python!" observing her with one eye. Yet, for a while, she gave no indication of her confirmation or denial. Finally she interrupted: "A bright-colored python. Very sweet-tempered."

The discussions ceased for a time. So that was the woman in the painting. After that, there was nothing to make them feel they had to keep their distance. They were no longer the slightest bit in awe of her. After all, she was just like any fat middle-aged woman you could see at the marketplace, the kind who would prattle on mindlessly while buying a penny's worth of green onion, or who would demand to check the scales when buying two ounces of meat. All the fellows, young and old alike, were very disappointed. They saw clearly how her hair, pulled up in a bun, was long unwashed, and her cheek bore an imprint from the mat that covered her straw pillow. And everybody saw clearly that she wore an ordinary light blue blouse, tight and old, which, since she had grown fat, bound up her body like a zongzi . On the front of her blouse was a smear of blood from a smashed mosquito. And besides all that, this beautiful snake-woman Sun Likun could also devour a big bowl of noodles, and if the noodles were too spicy, she could also open her mouth inelegantly and slurp them down with a "shee-hoo, shee-hoo!" sound, and after eating the noodles, her exquisite, naturally pure white teeth would also have some red chili skins or green onion slivers caught between them. She was so down-to-earth. Everybody was really disappointed.

One night, when desire and mosquitos buzzed through the air together, several of the young men climbed the surrounding wall to see how Sun Likun protected herself under her mosquito net. Suddenly, the window was pushed open from the inside with a bang. In the window frame stood Sun Likun, striking a provocative bitchy pose, hands on her hips, wearing a sweat-soaked sleeveless undershirt, which under the dusty lamplight appeared both sticky and wrinkled.

"What's so great to look at? Tell me so I can look, too!" Sun Likun laughed spitefully.

That sleeveless undershirt she had on was truly awful; it had been washed so many times that its texture seemed to have dissolved. When she moved and the streetlights caught it, the men could see how the transparent undershirt collapsed over her flesh, leaving everything, whether concave or convex, clearly distinguishable.

Some of the young fellows were practically naked themselves, except for their briefs, yet they were more embarrassed than she. Like frogs dropping into a pond, they jumped off the wall one after the other.

"What did'ja see? Huh?" She taunted them with her victory, ever more ferocious and spiteful.

"There wasn't much to see," one of the young fellows shot back mockingly, putting on the airs of a sophisticated city boy.

"Of course there's nothing to see. Anything your mother's got, I've got!" she replied.

This last remark defeated the young men completely. Hearing her counterattack in this manner, they crossed their eyes, just as when Xu Xian pulled back the bed curtains and saw Lady White in her original snake form. They had never imagined that a woman who had been like an Immortal and a dream could so easily give up her modesty and dignity after being penned up for two years.

In the dog days, Sun Likun would stand leaning against the window frame, always in that same beat-up undershirt, batting the air with a palm-leaf fan. When the construction workers chewed melon seeds, they would share some with her. When they smoked, she would beg cigarettes off them. She quickly developed an addiction and smoked more ferociously than the men. Soon no one could afford to supply her any more, so she told them to pick up their cigarette butts off the ground and just give those to her to smoke. The young fellows piled up the butts, tore the slogans off some big-character posters, wrapped the butts up in the paper and handed them over to her. They all knew that her wages had been stopped and her bank account frozen, but then, this treatment was normal for any prisoner serving a long sentence, especially one styled as an "ox-devil snake goddess."

One day, one of the young fellows came to Sun Likun wielding a bag of cigarette butts and said, "They say you can put your foot on your head. I want to see you do that."

She crossed her arms and thought for a while, then said, "What if I don't?"

"If you don't do it, no more cigarette butts. Every time we bend over to pick up a butt, that equals one kowtow. You think that comes cheap?"

Again she thought for a while. The construction workers had stopped playing cards and carousing and were craning their necks in unison toward the window, like a gaggle of geese waiting to be fed. Suddenly, Sun Likun grabbed her heel and pointed it skyward. Her white, thick stocky leg, shaped like a daikon radish yet straight as a writing brush, suddenly swung up vertically before the eyes of her audience, her two legs together forming the numeral 1, exposing her tattered pink floral panties. The construction workers found they could not recall the proper significance of those two famous legs, because now they had so many improper connotations.

The workers were still thinking of those connotations when they pleaded and demanded that she play the other leg for them. The famous dancer Sun Likun, locked in her cagelike pen, had turned into a circus monkey, playing her formerly famous pair of legs to men, young and old, whose bodies were covered with lustful sweat. Yet when displayed in succession, her two peerlessly beautiful legs, though now thick and corpulent, testified to their inexhaustible and profound meaning, their former significance. During this display, the construction workers imagined other scenes: these legs abundant with strength yet flexible as white pythons coiling around their flesh, coiling around the downy nakedness of that pink-bodied Soviet dancer. Those two legs of hers could easily coil around ten of those furry foreigners.

Sun Likun put her leg down, leaned one shoulder against the window frame, and with her eyes half-closed eyes in a sultry expression, thrust out her palm for the cigarette butts. The young fellow standing on the wall handed her the poster-paper bag and felt his hands grazed by her fingernails. He saw her pale face flush red in that instant. Either the cigarette butts or perhaps the displaying of her legs had given her a sudden ecstatic rush.

A downy ring above her upper lip was seeped with perspiration. Her eyebrows and eyelashes were thick. It was said that this beautiful snake-woman was not a pure Han Chinese, that drops of either Hui or Qiang blood had found their way into her. The worker was so close to her he could clearly see a red mole on the bottom of her eyelid. Afterward, when he told his workmates about this mole, an older worker said it was a bad omen. It meant that this woman could never be without a man, that the space between her legs could never be idle.

It was about this time that the construction workers started carrying their buckets under her window when they washed up. Their white undershorts, when soaked through, became a second skin. As they washed, they sang,

Girl, you are like tofu lees,

Eyes so pretty men knock their knees.

Sometime in October of 1970, a very different person arrived on the scene. He was in his early twenties, neither tall nor short. His face was fresh, neither dark nor light, with two swordlike eyebrows pointing at his temples. He wore an olive woolen military uniform. In the places where the insignias had hung on the collar and shoulders, the material had a deeper hue, and the texture was newer. This was proof that the woolen uniform was real, that this young man's air of superiority was warranted. He was a "cadre kid." The woolen uniform was so broad and heavy that the young man, his slim body bent slightly forward, was almost carrying it rather than wearing it. But it was precisely the large size of his uniform and the small size of his body that gave him a peculiar air of casual elegance. The young man's strides were long, and he walked with his hands behind his back as if he were some kind of old warlord with "people clearing the way in front and a young guard running up behind."

He stood reverently on that dilapidated construction site, as if surveying an ancient battlefield. All the construction workers stopped to watch the young man, their taunting bawdy songs broken off in their mouths and the paper strips from big-character posters stuck to their hands. There was something anachronistic and unusual about this young man's appearance and bearing. The derision and disdain in his eyes made the men think he had clout. His eyes were clear and feminine; his shyness was in the dark part of his eyes, and his cruelty was in the whites. When he looked at Sun Likun, he used the dark part, and when he looked at the construction workers, he used the whites.

In this aloof manner, the young man wandered around the dilapidated site, kicking half a brick or a seat cushion of posters--several dozen layers of big-character posters of various content stacked on top of each other and pasted together to form a cushion more durable than those made from leather hides. As the young man stopped and stood under Sun Likun's window, his regal bearing and faultless comportment made the construction workers think for once of a song that was not crude: "Chairman Mao Journeys to All Parts of Our Vast Motherland."

As soon as she saw the young man, Sun Likun put down the cigarette she had just finished rolling. She had spent her whole morning on this project, scraping out the contents of several dozen fingernail-sized cigarette butts and rolling them in paper discarded from an early draft of a self-criticism. Naturally, she was reluctant to let go of it completely, so for the time being she secreted it in her blouse pocket, intending to smoke it after the young man left. For the moment, she was unwilling to figure out why she couldn't bring herself to smoke this homemade, disgusting and unseemly cigarette in front of this twenty-something young man. She would wait until the calm of night to think about it. She would like to save the memory and savor it in years to come. The men she had been with in the past had all been good-looking; in fact, most had earned their living off their good looks. Many were her dance partners, with legs and shoulders that looked as if they were sculpted out of living rock, with eyes clear and luminous, yet vacant. By contrast, this one was not yet fully formed. He still had a fair amount of growing up to do.

The young man, standing with both hands behind his back and his legs planted wide apart, looked directly toward her. The timidity in his eyes and the light smirk on the corner of his mouth were at odds, betraying one another. He watched Sun Likun for a few minutes, then, with long paces, strode away.

On the dilapidated site the vulgar activity resumed. The construction workers again started picking up cigarette butts for Sun Likun. One of them unearthed the barely smoked cigarette the young man had dropped on the ground. It had been stamped into the soft mud by the young man's steel-toed boots, so the worker had to dig for a while with his fingertips before he unearthed it. One of the others who saw it said in awe, "It's Great China brand!"

The next day, the young man appeared again. The workers had started calling him "wool suit" behind his back. He still had the air of someone just passing through. That day Sun Likun had not put on her old perennial, the completely threadbare denim work shirt. Instead, she had changed into a fine sea blue sweater. Even though the sleeves had unraveled into a ball of jumbled yarn, the sweater still gave her body a bit of a curved profile.

The young man was riding a racing bike, its entire frame an oily metallic black without a hint of color or decoration. The workers gasped in admiration at this bike, regretting that such a sleek mount didn't have a pretty saddle. Had it been up to them, they would have draped it in red and green, coiling two pounds of colored plastic cord around it! The young man remained astride his bicycle with one foot on a pedal and the other on the ground for support. Everyone noticed how his broad pants legs were tucked into his short leather boots, lending just a touch of jauntiness to his clean-cut appearance. He lifted his hand to the brim of his cap and pushed it back, revealing pitch black hair underneath. He was wearing a snow white pair of gloves and used a snow white finger to adjust the brim of his cap. The gesture gave him a dignified but paradoxical air: a commander who still smelled of his mother's milk. From that time on, that pose--the index finger raised to the brim of his hat--stuck in Sun Likun's eyes, so that whenever she would close them, it would replicate itself everywhere, again and again to the point of her exhaustion.

That day, the young man's eyes and Sun Likun's met. Just like the headlights of two cars winding toward each other along a narrow mountain road, both with a premonition of rolling over and falling into the abyss at the side of the road, yet neither yielding to the other, neither extinguishing its lights, and if they both fall into the abyss, then so be it. The construction workers saw the beautiful snake-woman inside her awaken from its hibernation and come squirming forth to the surface. Her two eyes appeared as if recharged.

Behind the young man, a thirtyish construction worker sang while urinating in the sand pit:

Who cares if it's a piece of shit

As long as it's got Omega on it!

The young man turned back and hissed, "Filthy beast." His sound was soft, his words a well-enunciated Standard Beijing Mandarin.

They all racked their brains to figure out what he had said. They all knew the words "filthy beast" but couldn't recognize them immediately in this antiseptic-sounding Beijing accent. "What's this `filthy beast' you're talking about?" someone demanded.

"Not you, certainly. You're not worthy to be called a filthy beast," the young man replied coolly. Every syllable was enunciated clearly and completely, just as if spoken by a radio announcer at the Central People's Broadcasting Station. Only well-brushed teeth could produce such crisp words and such pure exemplary intonation.

The construction worker at the sandpit bent over, grabbed a large chunk of sandstone in one hand and made as if to pitch it, grenade-like, at the young man. The young man remained completely motionless. His thin single-fold eyelids narrowed. "Try it," he said slowly.

The construction worker dropped the chunk of stone he was holding and picked up another. This one was glistening with urine and was even hotter and heavier. Again he struck a pose as if to hurl it, yet he stepped back almost imperceptibly.

"If you make one move, you won't be here tomorrow. Try it," the young man said.

(Continues...)

Copyright © 1999 Geling Yan. All rights reserved.