Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Introduction | p. xii |

| Notes to the Reader | p. xvi |

| Remember China, Nan Chung | p. xix |

| Mastering the Fundamentals | |

| The Meaning of Rice | p. 3 |

| Steamed Rice | p. 7 |

| Flavored Sweet Rice | p. 8 |

| Fried Rice | p. 9 |

| Tender Chicken on Rice | p. 10 |

| Tender Beef on Rice | p. 12 |

| Chicken Porridge | p. 13 |

| Stir-Fried Frog on Rice | p. 14 |

| Savory Rice Dumplings | p. 16 |

| Peanut Rice Dumplings | p. 18 |

| The Breath of a Wok | p. 20 |

| Chicken with Cashews | p. 24 |

| Tomato Beef | p. 25 |

| Stir-Fried Chicken with Baby Corn and Straw Mushrooms | p. 26 |

| Stir-Fried Eggs with Barbecued Pork | p. 27 |

| Baba's Stir-Fried Butterfly Fish and Bean Sprouts | p. 28 |

| Stir-Fried Asparagus with Shrimp | p. 29 |

| Stir-Fried Squid | p. 30 |

| Beef Chow Fun | p. 31 |

| Singapore Rice Noodles | p. 32 |

| The Art of Steaming | p. 33 |

| Steamed Oyster and Water Chestnut Pork Cake | p. 37 |

| Steamed Pork Cake with Salted Duck Egg | p. 38 |

| Steamed Egg Custard | p. 39 |

| Steamed Tangerine Beef | p. 40 |

| Steamed Spareribs with Black Bean Sauce | p. 41 |

| Steamed Spareribs with Plum Sauce | p. 42 |

| Steamed Sole with Black Bean Sauce | p. 43 |

| Steamed Chicken with Lily Buds, Cloud Ears, and Mushrooms | p. 44 |

| Steamed Rock Cod | p. 45 |

| Steamed Sponge Cake | p. 46 |

| Shreds of Ginger Like Blades of Grass | p. 47 |

| Fried White Fish | p. 51 |

| Drunken Chicken | p. 52 |

| Braised Beef | p. 54 |

| Braised Sweet and Sour Spareribs | p. 55 |

| Nom Yu Spareribs | p. 56 |

| Lemongrass Pork Chops | p. 57 |

| Rock Sugar Ginger Chicken | p. 58 |

| Lemon Chicken | p. 59 |

| Seafood Sandpot | p. 60 |

| Sandpot Braised Lamb | p. 62 |

| Chestnuts and Mushrooms Braised with Chicken | p. 64 |

| Chicken and Corn Soup | p. 65 |

| Seafood Noodle Soup | p. 66 |

| Clear Soup Noodles | p. 67 |

| Fuzzy Melon Soup | p. 68 |

| Cabbage Noodle Soup | p. 69 |

| Family-Style Winter Melon Soup | p. 70 |

| Hot-and-Sour Soup | p. 71 |

| Sweetened Tofu Soup | p. 72 |

| Going to Market with Mama | p. 73 |

| Shrimp with Spinach and Tofu | p. 77 |

| Braised Mushrooms | p. 78 |

| Braised Cabbage and Mushrooms | p. 79 |

| Sprouting Soybeans | p. 80 |

| Grandfather's Stir-Fried Soybean Sprouts | p. 82 |

| Stir-Fried Bean Sprouts and Yellow Chives | p. 83 |

| Lotus Root Stir-Fry | p. 84 |

| Stir-Fried Egg and Chinese Chives | p. 85 |

| Stir-Fried Five Spice Tofu and Vegetables | p. 86 |

| Stir-Fried Chinese Broccoli | p. 87 |

| Stir-Fried Chinese Broccoli and Bacon | p. 88 |

| Braised Taro and Chinese Bacon | p. 89 |

| Stir-Fried Long Beans with Red Bell Peppers | p. 90 |

| Long Bean Stir-Fry | p. 91 |

| Stir-Fried Amaranth | p. 92 |

| Stir-Fried Water Spinach | p. 93 |

| Stir-Fried Cloud Ears and Luffa | p. 94 |

| Eggplant in Garlic Sauce | p. 95 |

| Stir-Fried Bitter Melon and Beef | p. 96 |

| Vegetable Lo Mein | p. 97 |

| Stuffed Fuzzy Melon | p. 98 |

| Braised Fuzzy Melon with Scallops | p. 99 |

| Cooking as a Meditation | p. 100 |

| The Art of Celebration | |

| The Good Omen of a Fighting Fish | p. 103 |

| Poached Steelhead Fish | p. 108 |

| Stir-Fried Bok Choy | p. 109 |

| White-Cut Chicken | p. 110 |

| Stir-Fried Clams in Black Bean Sauce | p. 111 |

| Stir-Fried Snow Pea Shoots | p. 112 |

| Glazed Roast Squab | p. 113 |

| Shark's Fin Soup | p. 114 |

| Oyster-Vegetable Lettuce Wraps | p. 116 |

| Stir-Fried Garlic Lettuce | p. 117 |

| Pepper and Salt Shrimp | p. 118 |

| Sweet and Sour Pork | p. 119 |

| Eight Precious Sweet Rice | p. 120 |

| Stir-Fried Scallops with Snow Peas and Peppers | p. 122 |

| New Year's Foods and Traditions | p. 123 |

| Buddha's Delight | p. 126 |

| Turnip Cake | p. 128 |

| Taro Root Cake | p. 130 |

| New Year's Cake | p. 132 |

| Water Chestnut Cake | p. 134 |

| Nom Yu Peanuts | p. 136 |

| Candied Walnuts | p. 137 |

| Sesame Balls | p. 138 |

| Sweetened Red Bean Paste | p. 139 |

| A Day Lived as if in China | p. 140 |

| Fancy Winter Melon Soup | p. 143 |

| West Lake Duck | p. 146 |

| Braised Nom Yu and Taro Duck | p. 148 |

| Stuffed Chicken Wings | p. 150 |

| Savory Rice Tamales | p. 152 |

| Sweet Rice Tamales | p. 154 |

| Pork Dumplings | p. 156 |

| Won Ton | p. 158 |

| Pot Stickers | p. 160 |

| Shrimp Dumplings | p. 162 |

| Stuffed Noodle Rolls | p. 164 |

| Spring Rolls | p. 166 |

| Scallion Cakes | p. 168 |

| Dutiful Daughter Returns Home | p. 170 |

| Salt-Roasted Chicken | p. 173 |

| Soy Sauce Chicken | p. 174 |

| Chinese Barbecued Pork | p. 176 |

| Barbecued Spareribs | p. 178 |

| Roast Duck | p. 180 |

| Chinese Bacon | p. 182 |

| Uncle Tommy's Roast Turkey | p. 184 |

| Mama's Rice Stuffing | p. 186 |

| Turkey Porridge | p. 188 |

| Achieving Yin-Yang Harmony | |

| Cooking as a Healing Art | p. 191 |

| Walnut Soup | p. 196 |

| Green Mung Bean Soup | p. 197 |

| Foxnut Soup | p. 198 |

| Sesame Tong Shui | p. 199 |

| Lotus Seed "Tea" | p. 200 |

| Sweetened Red Bean Soup | p. 201 |

| Peanut Soup | p. 202 |

| Almond Soup | p. 203 |

| Dried Sweet Potato Soup | p. 204 |

| Sweet Potato and Lotus Seed Soup | p. 205 |

| Dragon Eye and Lotus Seed "Tea" | p. 206 |

| Double-Steamed Papaya and Snow Fungus Soup | p. 207 |

| Double-Steamed Asian Pears | p. 208 |

| Homemade Soy Milk | p. 209 |

| Savory Soy Milk | p. 210 |

| Fresh Fig and Honey Date Soup | p. 211 |

| Soybean and Sparerib Soup | p. 212 |

| Dried Fig Apple, and Almond Soup | p. 213 |

| Ching Bo Leung Soup | p. 214 |

| Green Turnip Soup | p. 215 |

| Four Flavors Soup | p. 216 |

| Chayote Carrot Soup | p. 217 |

| Watercress Soup | p. 218 |

| Yen Yen's Winter Melon Soup | p. 219 |

| Herbal Winter Melon Soup | p. 220 |

| Mustard Green Soup | p. 221 |

| Gingko Nut Porridge | p. 222 |

| Snow Fungus Soup | p. 224 |

| American Ginseng Chicken Soup | p. 225 |

| Baba's Mama's Dong Quai and Restorative Foods | p. 226 |

| Dong Quai Soup | p. 230 |

| Lotus Root Soup | p. 231 |

| Korean Ginseng Soup | p. 232 |

| Homemade Chicken Broth | p. 234 |

| Double-Steamed Black Chicken Soup | p. 235 |

| Chicken Wine Soup | p. 236 |

| Pickled Pig's Feet | p. 238 |

| Beef and White Turnip Soup | p. 240 |

| Shopping like a Sleuth | p. 241 |

| Glossary | p. 246 |

| Index | p. 269 |

| Table of Contents provided by Syndetics. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

In Chinese cooking, every ingredient and dish is imbued with its own brilliance and lore. When I was a young girl growing up in a traditional Chinese home in San Francisco, this knowledge was passed on to me through a lifetime of meals, conversations, celebrations, and rituals. I felt every food we ate in our home had a story. "Eat rice porridge,jook,"Mama would say, "so you will live a long life." Or, "Drink the winter melon soup to preserve your complexion and to cool your body in the summer heat." Early on, my brother Douglas and I observed that the principles of yin and yang -- a balance of opposites -- were integrated into our everyday fare. For example, vegetables considered cooling, such as bean sprouts, were stir-fried with ginger, which is warming. Or stir-fried and deep-fat fried dishes were eaten with poached or steamed dishes in the same meal to offset the fatty qualities of the fried dishes. After a rich meal special nourishing soups were served to restore balance in the body.

Today, the brilliant harmony of Chinese cooking is gaining recognition. Chinese cuisine uses spare amounts of protein and a minimum of oil. Carbohydrates comprise essentially 80 percent of the diet and, in Southern China, this is primarily vegetables and rice, a nonallergenic complex carbohydrate that is one of the easiest foods to digest. Herbs and foods like ginseng, soybeans, gingko nuts, and ginger, which the Chinese have integrated into their diet for thousands of years, are now being accepted by the West as particularly beneficial for health. Many of the vegetables in the Chinese diet, especially greens like bok choy, are rich in beta carotene, other vitamins, phytochemicals, and minerals, and the favored technique of stir-frying preserves the vegetables' nutrients.

My parents have impressed upon me their love of food as they had learned it in China. l grew up to appreciate every aspect of cooking, from shopping to preparation to the rituals of eating. This lifelong influence led me to my career as a food stylist and recipe developer. My father, Baba, often warned Douglas and me about certain foods. Chow mein and fried dim sum, he said, were too warming,yeet hay,or toxic, if eaten in excess. On the other hand, most vegetables and fruits were cooling,leung,and therefore especially good to eat during the summer. He never actually explained to us precisely what "too warming" or "too cooling" meant but, somehow, we accepted it and allowed that he was right.

Still, my brother and I listened to our parents' stories with only half an ear. When Mann served Dried Fig, Apple, and Almond Soup and reminded us that it was "soothing for our bodies,yun,"we didn't really care. Instead, we could hardly wait to sink our teeth into a pizza, a hamburger, or a Swanson chicken pot pie, foods that we somehow knew wereyeet hay,but were too much a part of the all-American life we led outside our home that we craved them anyway.

Both my parents brought from China the traditions of food and cooking as they had practiced them in their homeland. To this day, they maintain one of the few traditional Chinese households among the members of our extended family in America, which numbers well over two hundred relatives. Although some of my relatives eat more pasta than rice, nay parents and the older uncles and aunties take pride in their expertise in classic Chinese cooking. They still center their diet around the principles of Chinese nutrition.

My family's kitchen was often fragrant with the aroma of homemade chicken broth simmering on the back burner of the stove. Invariably, bok choy was draining in a colander, while a fresh chicken hung on a rod over the counter to air-dry briefly before it was braised or roasted. Instead of boxes of commercial cereals, our kitchen cupboards were filled with jars of indigenous Chinese ingredients like lotus seeds, dried mushrooms, various soy sauces, cellophane noodles, and curious-looking herbs like ginseng, red dates, and angelica, ordong quai.Instead of milk and butter (dairy products are not part of Chinese cuisine), our refrigerator shelves were more likely to have tofu, ground bean sauce, ginger, and lotus root. In the pantry sat a 100-pound sack of rice.

Like many first-generation Americans, I didn't give my culinary heritage much thought until I was well into adulthood. Growing up in San Francisco, I ate Cantonese home-style food every day. These were not dishes found on restaurant menus, but rich, savory dishes with pure, simple flavors that are the hallmark of a home cook. Whether it was a simple weeknight supper or a more elaborate weekend meal, my parents wanted us to know why, in all of China, the Cantonese were considered to be the best cooks. Their cuisine is the most highly developed -- it has the broadest range of flavors, yet the subtlest of tastes. Later I would learn that the concept of foods having "warming" and "cooling" characteristics is especially revered by the Cantonese and manifests itself in their cooking. All the special soups we drank for nourishing and harmonizing our bodies came from a distinctly Cantonese tradition, one not found in any other part of China.

Only recently have I realized that I had taken my marvelous Cantonese culinary heritage for granted. Even members of my extended family have, like me, expanded their diets far beyond Cantonese fare. My cousin tells me that his wife is an excellent Italian cook. When it comes to Chinese food however, she cannot surpass the quality of their local take-out. While the cousins of my generation and their children enjoy Chinese traditions, only a few of them seem to have maintained the knowledge of the traditional recipes they were raised with. Who has time to learn the family recipes and digest their meaning and importance? My Auntie Bertha, who cooked countless memorable meals for me when I was a child, tells me she has forgotten most of her Chinese dishes; she says it is easier to cook simple American-style meals.

On my visits to San Francisco, Mama's delicious cooking stirred my taste memory, and I began to notice how much healthier I felt after several days of home cooking. As I began to record my family's recipes, I realized there were huge gaps in my knowledge, having learned Chinese cooking only through casual observation and not from formal study. Even with my professional cooking experience and natural familiarity with Chinese cuisine, it required energetic detective work to decipher and understand some of the recipes. For Chinese cooking is as ancient as its culture, with layers of meaning and wisdom that cannot be easily explained. No one member of my family could teach me every recipe or answer all my questions. I acquired most of my knowledge from my parents, but relatives and family friends all offered little bits of information that I pieced together. The power and wisdom of Chinese cooking goes far beyond simply mastering the more complex cooking techniques or even knowing the ingredients. For me, the principles that govern Chinese cooking and nutrition are far more intriguing than the Western notions of nutrition, with its focus on cholesterol, vitamins, minerals, fiber, carbohydrates, protein, and fits in the diet. It is a cuisine based on opposites, the yin-yang principles of cooking. This philosophy is so instinctively ingrained in my family that it was hard for them to articulate it verbally. I recognized that if I didn't begin questioning my parents, grandmother, aunts, and uncles, the wisdom of their diet and the lore of our culinary heritage would be irretrievably lost. It became clear that I needed to look to the past to understand the present.

I recorded my family's recipes without Americanizing the ingredients. There are those who offer substitutes for traditional Chinese ingredients, but this fails to acknowledge the genius of Chinese cooking. There is a reason for thousands of years of reverence for certain combinations. Recipes that offer, for example, Kentucky string beans as a substitute for Chinese long beans fail to grasp the Chinese nutritional perspective. While both vegetables have a similar crunchiness and might seem comparable, the Chinese long bean is the only vegetable the Cantonese consider neutral, neither too yin, "cooling," nor too yang, "warming," and is the only vegetable women are allowed to eat after giving birth. Cantonese believe most vegetables and fruits are "cooling" and, therefore, dangerous for a new mother, especially in the first month after she gives birth.

The recipes in this book include some that do not require exotic Chinese ingredients. Not every dish needs a specialty ingredient of labor-intensive chopping and shredding but, in all truthfulness, if you genuinely desire to cook Chinese dishes, you will need exotic ingredients, along with the time to properly prepare them. Some cooks will suggest using canned water chestnuts in place of fresh, but it is my feeling that if fresh are not available, the recipe is not worth making. For me, using canned water chestnuts is like using canned potatoes. In some areas, I've simplified recipes by calling for the food processor to puree ingredients. But, overall, I have tried to preserve the traditional ingredients and techniques as much as possible, preferring to hand-shred ginger and vegetables rather than feed them through a food processor.

The recipes reflect the range of mastery of the Cantonese home cook. The rich flavors of home-style cooking include basic stir-fry recipes, steamed recipes, rice dishes, braises, and soups; my family cooked these on most weeknights. Also included are the auspicious and more elaborate foods connected with New Year's and special occasions. Some of these recipes have an old-world quality about them, reflecting an era when people had more time to cook. Finally, the healing remedies are intended to restore harmony and strength to the body for proper yin-yang balance.

Chinese culinary healing, while essentially overlooked in the West, remains vital to Cantonese culture. To restore the natural balance in our bodies, my family countered the rich and delicious foods we ate regularly with what I callyin-yang concoctions,or special soups made according to a more than thousand-year-old tradition. I have written these recipes and explained their health benefits as my family practices them. All the recipes were eaten in moderation, and never considered a substitute for professional medical attention. Sometimes, the recipes or stories behind them vary slightly from family to family, and from village to village. I offer them here as they were taught to me.

My parents' approach to cooking is Zen-like: attentive to detail and masterful. They are not formally trained in cooking, yet they share a passion for food that is common among many Chinese. They have great esteem for the meaning and symbolism of food as well as respect for age-old remedies. The everyday rituals of properly selecting produce, slicing meat, washing rice, and presenting a meal, which I have inherited from my family, have given me an aesthetic insight into life. The slow emergence of these truths has allowed me to see the meaning of my own cooking as a metaphor for life.

Copyright © 1999 by Grace Young

REMEMBER CHINA, NAN CHUNG

My older brother, Douglas, was born in San Francisco just after the Communists took control of China. My grandfather, Gunggung, who lived in Shanghai, gave Douglas his Chinese name, Nan Chung, which means "Remember China." Grandfather was intent that this first grandchild, born in a foreign land, would never forget his family in China, and always reflect on his family's long history and tradition. Indeed, none of his grandchildren would be born in China. Growing up in America, Douglas and I behaved more like American children than Chinese. Our taste, our interests, our goals were all American. It is only now, after nearly fifty years, that I have begun to heed Gunggung's instruction to "Remember China."

Nothing can more powerfully transport me across time and geography to the intimacy of my childhood home than the taste or small of Cantonese home cooking. I naively set about writing my family's recipes with the thought that this project would be solely about cooking. But with each question about a recipe came a memory from my parents and, with each memory, I was led into a world I hadn't realized belonged to me. I listened to Mama reminisce about the weeks of preparation at her grandmother's kitchen in Hong Kong before the New Year's feast, about the servants hand-grinding rice to make flour for all the special cakes. My relatives also discovered photographs they had forgotten existed. One was a fragile sepia portrait of my great-grandmother, her feet bound. I studied the image trying to grasp my blood relationship to this woman, separated by only three generations. Another elegant studio portrait shows Baba's family in Canton, in 1934. In it I see the young faces of my father, my uncles, my aunts. Who were these innocent souls before they carved their life paths? Few photographs survived that other life, making its reality ever more ephemeral. This glimpse into my own history was but one of the treasures uncovered in the process of collecting my family's recipes.

A remarkable chapter opened in my relationship with my parents when I began recording our family's culinary heritage. Despite their unfathomable reticence to talk about themselves, eventually, as I persisted in my questions, they slowly responded to my desire to learn. "Show me howyouchoose bok choy, howyouprefer to stir-fry. Describe for me how it was in Shanghai and Canton when you were little. Did the water chestnuts taste like this or were they sweeter, the lotus root smaller, the tea more fragrant?" My parents, each in his or her own way, came to enjoy teaching me. Baba, whose routine is to monitor the stock market while drifting in and out of catnaps, suddenly had a list of cooking lessons. Mama, ever the matriarch, was only too happy to instruct me on her highly specific principles for produce shopping, or to confer with my aunties on recipes I requested. I, in turn, was grateful for this new relationship. We talked not only about cooking but also of their recollections of life in China and in San Francisco's Chinatown at mid-century. Flattered by my interest, they stretched their memories to unearth stories and reclaim their forgotten past. Baba mentions to me one day that he had owned a restaurant in Chinatown in the 1940s called the Grant Cafe, on the corner of Bush and Grant Avenues, which served Chinese and American food. But when I ask for details, it is difficult to get him to elaborate. His reluctance to talk about what he considers private tempers how much I learn about his past.

On one visit Auntie Margaret and Auntie Elaine describe the thrill of being driven by my Yee Gu Ma (second-eldest aunt) in her Packard in 1937, when Grant Avenue was a two-way street. Few Chinese women drove in those days, but my uncle, George Jew, was a "modern man" who wanted my aunt to drive. Baba wonders aloud about whether it was a Buick or a Packard, but I am lost in thought imagining my petite aunt wielding a big car down Grant Avenue, on her way to Market Street with her younger sisters and brother.

The San Francisco Chinatown of my youth is barely evident in the Chinatown of today. In the 1960s it was a charming, intimate community inhabited by legions of old-timers, known aslo wah kue,and locals. On any given day I would see Uncle Kai Bock sitting on a stoop on Washington Street; run into Auntie Margaret at her restaurant, Sun Ya, or stop to see Auntie Anna or Uncle Roy at Wing Sing Chong market. My Auntie Anna knew everyone who came into her store, and I was convinced she was Chinatown's honorary mayor. To this day you can barely walk two steps with Auntie Anna without someone greeting her. Every Friday night nay family went out to eat. Whichever restaurant it was, Sai Yuen, Far East Cafe, or Sun Hung Heung, Baba would stroll into the kitchen to order our food. This was no small feat. Restaurant kitchens were off-limits to everyone but staff, but Baba sold liquor to all the Chinese restaurants, and often the owner was the chef. Rejoining us, he would tell us which dishes were the freshest and best to eat that day. I still believe he must have observed many professional cooking secrets during these visits, and I can't recall ever eating in a restaurant where Baba didn't know the chef or owner. Baba seemed to know everyone.

In those days, Chinatown was the safest neighborhood in all of San Francisco. My cousins Cindy and Kim stayed with their grandparents in Chinatown on weekends and Gunggung would take them for a late-night snack,siu ye,of won ton noodles, chow mein, or rice porridge,jook,at two or three in the morning. Their paternal great-grandfather, Jew Chong Quai, was one of the wealthiest merchants in Chinatown in the early 1920s. San Francisco had a thriving bay shrimp industry for more than eighty years, and he had a shrimp cannery in Hunter's Point in addition to being an importer and exporter of bean sauce(fu yu).

I have warm memories of standing on Grant Avenue for the Chinese New Year's parade and watching for my glamorous Auntie Katheryn on the Pan Am float and my cousin Carol who led the St. Mary's drum corp. Today, Chinatown is still the vital center of the Chinese community, but the purity of its Cantonese soul is lost amidst the Wax Museum, McDonald's, Arab merchants hawking cameras on Grant Avenue, and the mixture of non-Cantonese Asian immigrants who have since moved in. Still, a few sights remind me of the Chinatown of old: the Bank of America on Grant Avenue with its classical Chinese architecture, the creation of my Uncle Stephen, an architect, as is the Imperial Palace Restaurant on Grant Avenue and the Cumberland Church on Jackson Street; my Uncle Larry's medical practice on Clay Street, one of the oldest original practices remaining; and, until recently, my Uncle William and Aunt Lil's family's restaurant, Sun Hung Heung, the oldest Chinese restaurant owned by one family, in operation since 1919. Another remaining point of pride is the Kong Chow Benevolent Association and Temple on Stockton Street, which my Uncle Donald was instrumental in building. This association serves the overseas Cantonese from two counties in China: Sunwui (where Baba's family was born) and Hokshan (where Mama's family was born).

When I think of the delicious food of my childhood beyond my own family's influences, I think of my beloved Uncle Tommy. He was an artist and a natural cook who had a special gift in the kitchen. His early death left an enormous void in the family. As a child, I enjoyed many a meal at Uncle Tommy and Auntie Bertha's home. I well remember the intoxicating aromas that would come from their kitchen, and tire taste of the food Uncle Tommy cooked.

It was out of this world. I have asked my cousins Sylvia, Kathy, and David for their father's recipes but, sadly, neither Auntie Bertha nor my cousins ever recorded them. Alas, they are but a sweet memory for all of us. We partook of his specialties without ever thinking there would come a time when we couldn't taste the pleasure of his cooking and company. A great cook's recipes are as unique as fingerprints.

My brother and I did not grow up sitting on our grandparents' laps, hearing tales of their youth. And it was not my parents' custom to speak much about their life in China. They came to America for economic and political reasons, to seek a better future. I once asked Mama a simple question about her parents, and was surprised that she couldn't answer me. "In China, we only knew what our parents told us. We never asked personal questions out of respect for our elders." Occasionally, my parents would share a story but, for the most part, they rarely divulged their remembrances. Perhaps, too, Mama and Baba weren't ready to speak of their former life and we were too young to care, or to know what to ask.

The year 1999 marks the 150th anniversary of the Gold Rush and the first major immigration of the Chinese people to America. Despite a century and a half of transplantation, Chinese cuisine remains alive and virtually unchanged -- testimony to the strengh of its traditions. The recipes my parents prepare today are not dramatically different from those of their parents and grandparents in China. Yet the Chinese of my generation stand at a crossroads: We maintain the desire to preserve our culinary heritage yet, like most Americans, have precious little time for cooking and honoring the old ways. We risk the loss of our great cooking rituals and along with them their spiritual enrichment. I have yet to find the web site for wisdom.

The time I have spent cooking with my parents, listening to their stories, and receiving their wisdom has allowed me to claim something of my cultural identity and heritage. To master Chinese cooking requires a lifetime of study, and I offer this book as an example of one family's culinary devotion. A knowledge of cooking passed from generation to generation offers a gift to the soul, one that appeals to all of the senses and affirms our deepest connection to life.

Copyright © 1999 by Grace Young

From GOING TO MARKET WITH MAMA

Mama is an expert in the art of selecting(gan).It embarrasses Mama when I say this because she doesn't perceive her expertise as anything special. One of my earliest memories, involves going to market with Mama and watching her choose her produce. As with many Chinese housewives, every ingredient Mama has ever bought has been carefully chosen for beauty(gan langde).Whether it was several pounds of snow peas or a few delicate papayas, each item was individually examined for fragrance, ripeness, and blemishes. If I ever brought borne produce chosen without careful examination, her dismay upon discovering something that was blemished would be palpable.

Partially from my parents' training and partially because I am a food stylist, I, too, am very particular when it comes to fresh produce. It baffles my husband, Michael, that I need to look at every fruit and vegetable stand along Canal and Mulberry Streets before I will make my selection. It upsets me to buy mangoes from one stand and then to see riper, more beautiful mangoes two stores down the block. My own perfectionism notwithstanding, it still astounds me how Mama will willingly walk to three or four markets until she finds bean sprouts that meet with her approval -- plump, short, and never limp.

As finicky as I think I am, Mama has an altogether higher standard of excellence. She is totally energized by the adventure of shopping for produce. Despite the fact that I am nearly thirty years her junior, I often cannot keep pace with her as she whips in and out of markets on Stockton or Clement Streets, as if on a treasure hunt. In every store she seems to know who the owner is, greeting him, complimenting him on his outstanding produce, while often politely asking him to check his storeroom for specialty items. Every vegetable has criteria that must be met and an equally serious list of what to avoid. Regardless of my admiration of Mama's expertise, she, too, will occasionally buy produce that disappoints her. Perplexed, she will confer with friends, seeking tips and advice, ever ardent to master the art of produce shopping.

We have a family friend, Chen Mei, who was raised on a farm in China and who almost unconsciously will pinch and squeeze Chinese turnips and taro root until she finds the perfect vegetable. She is so proficient at choosing produce that Mama often instructs me to learn from Chen Mei. For example, in selecting Chinese broccoli, she advises that the bunch should never have open flowers. Buds are acceptable, although Chen Mei warns me that sometimes the buds have insects hidden inside, which explains why some people wash broccoli in salt water, hoping to force the insects out. Some Hong Kong food connoisseurs eat only the stalks to avoid this danger. (There is also a superstition that if you eat broccoli flowers, you will become deaf.) When choosing the best fuzzy melon(zeet qwa),Chen Mei insists it be bright green, stubby, fat, and have tiny hairs that lightly prick you. If the melon is hairless, it's too old and not worth cooking. On the other hand, the most coveted winter melon(doong qwa)must be as old as possible to be worthy of selection. The outside of the melon must be well covered with white powder, and the rind must be very hard, all good signs of proper maturity. My Auntie Katheryn reminisces that winter melon rind in China, even after hours of cooking, would seem as though it was as hard as tin. "Sadly, American winter melon rind is so soft," she says, but "at least choose the end pieces, which are preferable to the center portion." (Winter melon is sold in pieces, much like watermelon.)

Years ago Mama and Auntie Katheryn used to commiserate on how inferior American produce was compared to Chinese produce. "Everything is grown bigger but is less flavorful." When I was a child, they spoke of fruits and vegetables from China as though they were from a fairy tale. All fruits had a crispness(choy hul)that the Chinese prize -- from plums and peaches to Asian pears which, unlike many American varieties, are soft and without fragrance. In China, most fruits and vegetables are picked before dawn and delivered to the markets early in the morning. Mama and Auntie Katheryn tasted that rare sweetness and crispness of just-harvested produce. Today, the quality of Asian produce available in America has improved tremendously because of the influx of Asian farmers. The variety and quality of produce is a far cry from what was available when we were growing up. In addition, the more exotic vegetables and fruits of China and Thailand, like lotus root, fresh lichees, and durian, are flown in when in season.

Sometimes as we race through the open-air markets, Mama will spot some farm-fresh produce, like bitter melons, that have just been brought out to be sold, and she will linger in front of the stand wanting to buy. I remind her we still have three in the refrigerator, which she is fully aware of, but flawless produce is hard for her to resist. Reluctantly she walks away explaining to me how perfect those bitter melons were -- light colored, fat, yet tapered like the shape of a rat, with the proper thick ridges. "Not," she says, "like the flavorless, skinny, dark green, bitter melons." Still, as particular as she is, she will not shop for anything she feels inexperienced at choosing. Fish and meat are Baba's domain and she will not risk wasting her time buying them. There are also certain vegetables she is less familiar with, like taro root, which she is reluctant to purchase.

I remember in the sixties, when supermarkets first began to wrap produce in cellophane, Mama would examine the scaled packages, frustrated that she couldn't touch the fruit to see for herself if the vegetable was indeed fine. It would annoy and embarrass my brother and me to hear Mama ask the clerk if the oranges were sweet. We'd ask Mama if she really thought he'd say no. Then she would say, "If he says yes and they're not sweet, I won't trust him again."

Although my parents will shop in a supermarket, their preference is to go to Chinatown. There, the demand for high quality and fresh ingredients naturally creates a market with high turnover. I believe this high standard manifests itself the more nutrient-rich foods the Chinese eat. Compare supermarket produce, which has often sat for days in a warehouse, with produce you see in Chinatown, where just-delivered boxes are sometimes eagerly emptied by customers on the street. Even at the butcher shop, Baba points out to me the difference in freshness between supermarket meat and the kind sold in a Chinese butcher shop. When we buy a piece of pork butt(moy tul),he has me touch the package and take note that the pork is not cold to the touch. "Just slaughtered," he says to me with a wink(sung seen tong zaw),and as we walk out of the shop I notice the truck parked in front delivering the slaughtered pigs.

Baba and Mama shop daily, which is possible for them to do because they are retired. However, even when they worked, they would never shop for produce only once a week or stock up on frozen or canned fruits or vegetables. Freshness is such an important requirement in Chinese cooking that the extra effort to shop more frequently is accepted willingly. They appreciate the difference you can taste when food issung seen(fresh).

In America, it is considered the height of luxury to call in an order to a fine market for home delivery. However, for the Chinese, allowing someone else to put produce into your bag, to do your selecting, would be unthinkable. It is impossible to assume that a stranger would take the proper care in selecting your food. The freshness and ripeness of the food you eat is so critical that you must personally oversee it if you are to be responsible to yourself and for your family's well-being. Lin Yu Tang, the great Chinese philosopher, wrote inThe Importance of Living,"For me, the philosophy of food seems to boil down to three things: freshness, flavor and texture. The best cook in the world cannot make a savory dish unless he has fresh things to cook with, and any cook can tell you that half the art of cooking lies in buying."

To my motherandmy father and, indeed, most Chinese people, selecting farm-fresh produce brings them pure delight and satisfaction. They literally glow, and beam, to bring home choice, blemish-free produce. And this glee lasts through every mouthful of the delectable dishes they prepare.

Shrimp with Spinach and Tofu

Leung Boon Ho Mai Baw Choy Dul Foo

San Francisco has an Indian summer for at least one week every year, when the temperatures can reach eighty or ninety degrees. It was then that Mama would make us Shrimp with Spinach and Tofu, a dish she remembers eating in Shanghai in the summer, when the weather was unbearably hot. We always ate it chilled and the fragrance of the sesame oil suits the cooling and refreshing taste of the spinach and tofu. Squeeze as much water as you can from the cooked spinach or the excess water will dilute the flavors.

2 squares firm tofu, about 6 ounces

1 1/2 pounds spinach, preferably young

2 tablespoons small Chinese dried shrimp, rised

1 tablespoon sesame oil

1/2 teaspoon salt

In a 1 1/2-quart saucepan, bring 2 cups water to a boil over high heat. Add the tofu and return to a boil. With a slotted spoon, remove the tofu and place on a rack to cool.

Remove all stems from the spinach. Wash spinach in several changes of cold water and drain thoroughly in a colander. Return water to a boil over high heat, and add the spinach. Cook until it is just limp, about 30 seconds. Drain and rinse under cold water.

Squeeze the spinach to remove excess water and form into a tight ball. Chop the spinach by cutting the ball into 1/4-inch slices. Place the spinach in a large bowl.

Cut the tofu into 1/8-inch dice. Finely chop the shrimp. Add the sesame oil, salt, tofu, and shrimp to the spinach, and toss to combine. Chill, if desired, or serve at room temperature.

Serves 4 to 6 as part of a multicourse meal.

Braised Mushrooms

Mun Doong Qwoo

Chinese dried mushrooms, also called black,winter mushrooms,orshiitake,as they are known in Japan, can vary broadly in quality and price. For everyday cooking I generally use inexpensive ones, which have thin brown caps and a soaking time of only about thirty minutes. However for this dish, since the mushrooms are the featured ingredient, ideally one should use high-quality mushrooms, such asfa qwoo;this name will not appear on the package in English. These can easily cost over fifty dollars a pound. The color of the caps is not as black as that of the less expensive variety, and they are much thicker in both appearance and texture. They require three to four hours to soak, and their flavor is meatier and more intense. People who know mushrooms can judge their quality just by looking at the caps.Fa qwoocaps have deep cracks and are said to resemble flowers. In presenting this dish, always place the caps on the platter stem-side down. Cookingfa qwoois reserved for special occasions.

4 Chinese dried oysters

20 medium Chinese dried mushrooms, preferablyfa qwoo,about 8 ounces

1/2 teaspoon sugar

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

2 slices ginger

2 tablespoons oyster flavored sauce

8 slices (2 by 1 by 1/4 inch) Smithfield ham

Cilantro sprigs, optional

Rinse the oysters in cold water. In a small bowl, soak the oysters in 1/2 cup cold water for 3 to 4 hours, or until soft. Drain and squeeze dry, reserving the soaking liquid.

In a medium bowl, soak the mushrooms in 1 1/3 cups cold water and sugar for 3 to 4 hours, or until softened (less time if inexpensive mushrooms are used). Drain and squeeze dry, reserving the soaking liquid. Cut off and discard stems, leaving the caps whole.

Heat a 14-inch flat-bottomed wok or skillet over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add the oil, ginger, oysters, and mushrooms, and stir-fry 1 minute. Add the oyster sauce, reduce heat to medium, and cook 1 minute. Add the reserved mushroom and oyster liquids and ham slices, and bring to a boil over medium heat. Cover, reduce heat to low, and simmer 30 minutes. Check the saucepan occasionally to make sure there is just enough liquid to simmer the mushrooms. Add a little water if necessary. Cook until only about 2 tablespoons of liquid is left in the pan and the mushrooms are tender. Discard the oysters. Place the mushroom caps and sauce on a platter and garnish with cilantro sprigs if desired. Serve immediately.

Serves 4 as part of a multicourse meal.

Braised Cabbage and Mushrooms

Doong Qwoo Mun Wong Gna Bock

Napa cabbage,wong gna bock,varies in its water content depending on how old it is. Younger cabbage has more water and, therefore, may not need the addition of any liquid as it cooks. Older cabbage is drier and is sweeter in flavor but will need the addition of broth to prevent it from sticking in the wok. Mama recalls that her family would buy ten to twelve heads of cabbage at a time in Shanghai and hang them in their kitchen to allow them to wilt and dry slightly over one to two weeks, to obtain this sweeter flavor. Their household had at least nine people to feed, so it was easy to use up that amount of cabbage in no time.

12 Chinese dried mushrooms

1/4 teaspoon sugar

8 large leaves Napa cabbage, about 1 pound

1 teaspoon plus 1 tablespoon vegetable oil

2 slices ginger

3/4 cup Homemade Chicken Broth

2 tablespoons oyster flavored sauce

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon thin soy sauce

2 teaspoons sesame oil

In a bowl, soak the dried mushrooms and sugar in 3/4 cup cold water for 30 minutes, or until softened. Drain and squeeze dry, reserving soaking liquid. Cut off and discard stems and halve the caps. Wash the cabbage leaves in several changes of cold water and drain thoroughly in a colander until dry to the touch. Trim 1/4 inch from stem end of the cabbage leaves and discard. Stack 2 to 3 cabbage leaves at a time and cut crosswise into 1/4-inch-wide shreds.

Heat a small saucepan over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add 1 teaspoon of oil and 1 slice of ginger, and stir-fry 30 seconds. Add reconstituted mushroom caps and stir-fry 1 minute. Add the reserved mushroom liquid and 1/2 cup chicken broth, and bring to a boil. Reduce heat to low, cover, and simmer 25 minutes. Check the saucepan occasionally to make sure there is just enough liquid for the mushrooms to simmer. Stir in oyster sauce.

Meanwhile, heat a 14-inch flat-bottomed wok or skillet over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add the remaining 1 tablespoon oil and ginger slice, and stir-fry 30 seconds. Add the cabbage and stir-fry 1 to 2 minutes, or until vegetable is slightly limp. Stir in the salt, remaining 1/4 cup chicken broth, soy sauce, and sesame oil and reduce heat to medium-low, cover, and simmer 5 minutes.

Transfer the cabbage to a platter with pan juices. Pour the mushrooms over the center of the cabbage and serve immediately.

Serves 4 as part of a multicourse meal.

Copyright © 1999 by Grace Young

From GOING TO MARKET WITH MAMA

Lotus Root Stir-Fry

Leen Gnul Siu Chow

In Buddhist culture, the lotus is a sacred symbol of purity. The root, which grows in mud, emerges clean and pure, unchanged by the mud. My Uncle Sam remembers eating raw, sliced lotus root at the August Moon Festival -- a time of year when lotus is plentiful in China. Its crisp texture is delightful whether raw or cooked.

This is one of my Auntie Anna's favorite dishes. She likes it because the combination of crisp lotus root, snow peas, cloud ears, and pickled vegetable is so pleasing. It is especially good if Chinese bacon is available. Fresh lotus root is sold in three connected sections -- the larger section is best for stir-fries, the two smaller sections are best for soups (Lotus Root Soup). Some produce markets precut the lotus root into sections and seal them in Cryovac. I prefer not to buy lotus root that has been wrapped, because it prevents me from checking to see if it has a clean, fresh smell.

Salted turnip is only available in Chinese supermarkets. There are many different kinds of salted turnip, which are not distinguished in English on the label. You'll have to ask for it by its Cantonese name,teem choy poe. Teem choy poeis available in 7-ounce packages; the slices are 3 to 5 inches long, 1/2 inch wide, and khaki colored.

1/4 cup cloud ears(wun yee)

1/4 cup lily buds(gum tzum)

7 pieces salted turnip(teem choy poe),about 2 ounces

1 large section lotus root, about 6 ounces

3 ounces Chinese Bacon, store-bought or homemade

1 1/2 teaspoons Shao Hsing rice cooking wine

1 teaspoon thin soy sauce

3/4 teaspoon sesame oil

3/4 teaspoon sugar

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon ground white pepper

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

4 thin slices ginger

8 ounces snow peas, strings removed

Place the cloud ears and lily buds in separate bowls. Pour about 1/2 cup cold water over each ingredient and soak for about 30 minutes to soften. When softened, drain and discard the water. Remove the hard spots from the cloud cars, and remove the hard end from the lily buds, tying each lily bud into a knot.

Meanwhile, soak the salted turnip in cold water to cover for 30 minutes. Drain. Cut each piece in half crosswise, then thinly cut length-wise into fine shreds and set aside.

Using a vegetable peeler, peel the lotus root, removing the rootlike strands, and rinse under cold water. Cut the lotus root in half length-wise and rinse again to remove any mud lodged in the root. Slice the lotus root into 1/4-inch-thick half moons. Rinse again in case there is any mud, and set aside to drain well.

Remove the hard rind from the Chinese bacon, and the thick piece of fat attached to the rind, and discard, Cut the bacon crosswise into very thin slices.

In a small bowl combine 3 tablespoons cold water, rice wine, soy sauce, sesame oil, sugar, salt, and pepper.

Heat a 14-inch flat-bottomed wok or skillet over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add the vegetable oil and ginger, and stir-fry 10 seconds. Add the Chinese bacon and stir-fry 45 seconds, Add the lotus root and stir-fry 1 minute. Add the snow peas, cloud ears, lily buds, and turnip, and stir-fry another minute. Swirl in the rice wine mixture and stir-fry 2 to 3 minutes, or until the lotus root is tender but still crisp, and the snow peas are bright green. Serve immediately.

Serves 4 to 6 as part of a multicourse meal.

Stir-Fried Egg and Chinese Chives

Gul Choy Chow Dan

There are three different kinds of Chinese chives; Chinese chives, yellow chives, and flowering garlic chives. This recipe uses Chinese chives(gul choy),which are green and look similar to Western chives, except that they are flat. They are said tosan hoot,or remove old blood from your system.

1 large bunch Chinese chives, about 4 ounces

4 large egg whites, beaten

2 teaspoons thin soy sauce

1 teaspoon sesame oil

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon ground white pepper

3 tablespoons vegetable oil

Wash the Chinese chives in several changes of cold water and drain thoroughly in a colander until dry to the touch. Cut the chives into 1/2-inch pieces.

Place the chives in a medium bowl. Add the egg whites, soy sauce, sesame oil, salt, and pepper, and stir to combine.

Heat a 14-inch flat-bottomed wok or skillet over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add the vegetable oil and egg mixture, and stir-fry 1 minute. Reduce heat to medium and cook another 1 to 2 minutes, or until eggs are set but not dry. Serve immediately.

Serves 4 as part of a multicourse meal.

Stir-Fried Five Spice Tofu and Vegetables

Nmm Heung Dul Foo Chow Saw Choy

Stir-fries can be time consuming -- finely shredding vegetables, soaking special ingredients, and measuring all the seasonings. But, in a stir-fry such as this, all the work is worth it when you taste the results. The tremendous array of vegetables and seasonings creates a range of textures, tastes, fragrances, and colors.

Five spice tofu is found in the refrigerator case of most Asian grocery stores. It is much firmer than even extra firm tofu, because all the excess water has been pressed out. The tofu is chocolate-colored and is sold in 2-inch squares or 2-by-3 1/2-inch blocks that are 1/2 to 1 inch thick. The dark color is the result of cooking the tofu with five spice seasoning, which both flavors and colors the tofu. See Lotus Root Stir-Fry for information onteem choy poe,or salted turnip.

4 Chinese dried mushrooms

2 ounces salted turnip(teem choy poe)

3 pieces five spice tofu(nmm heung dul foo gawn),about 4 ounces

1 carrot

1 celery stalk

3 fresh water chestnuts

1 red bell pepper

1 yellow bell pepper

1 tablespoon thin soy sauce

1 1/2 teaspoons Shao Hsing rice cooking wine

1 teaspoon sesame oil

1/4 teaspoon sugar

1/4 teaspoon ground white pepper

1/4 teaspoon salt

4 tablespoons vegetable oil

2 scallions, cut into 2-inch sections

Cilantro sprigs

In a medium bowl, soak the mushrooms in 1/4 cup cold water for 30 minutes, or until softened. Drain and squeeze dry (reserve the soaking liquid for use in soups). Cut off and discard the stems and thinly slice the caps. In a small bowl, soak the salted turnip in 1 cup cold water for 30 minutes, or until vegetable is only mildly salty. Rinse the salted turnip and pat dry. Cut it into fine shreds to make about 1/2 cup. Discard the water.

Cut the tofu, carrot, and celery into julienne strips. Peel the water chestnuts with a paring knife and then thinly slice. Cut the red and yellow peppers into thin slivers. In a small bowl, combine the soy sauce, rice wine, sesame oil, sugar, white pepper, and 1/8 teaspoon salt. Set aside.

Heat a 14-inch flat-bottomed wok or skillet over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add 2 tablespoons vegetable oil and the tofu, spreading it in the wok. Sprinkle on the remaining 1/8 teaspoon salt, reduce the temperature to medium, and cook undisturbed 1 to 2 minutes, letting the tofu begin to brown. Then, using a metal spatula, carefully turn the tofu and continue cooking undisturbed 3 to 4 minutes, or until the tofu is lightly browned. Transfer to a plate and set aside.

Increase the heat to high and add 1 tablespoon vegetable oil and the julienned carrot to the wok; stir-fry 1 minute. Add the remaining 1 tablespoon oil, mushrooms, salted turnip, celery, water chestnuts, peppers, and scallions, and stir-fry 1 minute. Swirl in the reserved soy sauce mixture and tofu, and stir-fry 2 to 3 minutes, or until the vegetables are crisp and tender. Garnish with cilantro sprigs. Serve immediately.

Serves 4 to 6 as part of a multicourse meal.

Stir-Fried Chinese Broccoli

Chow Gai Lan

Chinese broccoli(gai lan)looks like a cross between basic supermarket broccoli and the Italian broccoli rabe. The vegetable tastes more like broccoli rabe with its big green leaves and its pungent bite. Stir-frying is the best way to cook Chinese broccoli, as it brings out the natural flavor, accented here with a touch of sugar, ginger, and rice wine. It will need to be washed and drained several hours before stir-frying, and it must be stir-fried in small amounts (about twelve ounces) to achieve the bestwok hay(see "The Breath of a Wok"). It's better to cook two separate recipes than to try to fit too much in the wok.

Choose broccoli that has buds and no flowers. If there are flowers, the broccoli is too old. The stalks are never as thick as those of regular broccoli, but if they are thicker than 1/2 inch, they need to be halved lengthwise. The vegetable is better in the colder months, but is available year-round in Chinese produce markets.

10 stalks Chinese broccoli(gai lan),about 12 ounces

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

3 slices ginger

1/4 teaspoon sugar

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon Shao Hsing rice cooking wine

Wash the broccoli in several changes of cold water and drain thoroughly in a colander until dry to the touch. Trim 1/4 inch from the bottom of each stalk, Stalks that are more than 1/2 inch in diameter should be peeled, then halved lengthwise. Cut the broccoli stalks and leaves into 2 1/2-inch-long pieces, keeping the stalk ends separate from the leaves and buds.

Heat a 14-inch flat-bottomed wok or skillet over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add the oil and ginger, and stir-fry 30 seconds. Add only the broccoli stalks and stir-fry 1 to 1 1/2 minutes until the stalks are bright green. Add the leaves, and continue cooking for 1 minute until the leaves are just limp.

Sprinkle on the sugar, salt, and rice wine. Stir-fry 2 to 3 minutes, or until the vegetables are just tender but still bright green. Serve immediately.

Serves 4 as part of a multicourse meal.

Stir-Fried Chinese Broccoli and Bacon

Lop Yok Chow Gai Lan

Chinese broccoli is especially good stir-fried with mellow-flavored Chinese Bacon, a touch of rice wine, sugar, and a hint of garlic. Chinese Bacon is available in Chinese meat markets (though you can make it yourself). To cut thin slices, use a sharp cleaver or a heavy-duty cook's knife, as it is hard and can be difficult to slice. (See Stir-Fried Chinese Broccoli, for information on broccoli.)

10 stalks Chinese broccoli(gal lan),about 12 ounces

3 ounces Chinese Bacon(lop yok),store-bought or homemade

1 teaspoon thin soy sauce

1 teaspoon Shao Hsing rice cooking wine

1/2 teaspoon sugar

2 teaspoons vegetable oil

2 garlic cloves, smashed and peeled

Wash the Chinese broccoli in several changes of cold water and drain thoroughly in a colander until dry to the touch. Trim 1/4 inch from the bottom of each stalk. Stalks that are more than 1/2 inch in diameter should be peeled with a paring knife, then halved length-wise. Cut the broccoli stalks and leaves into 2 1/2-inch-long pieces, keeping the stalk ends separate from the leaves and buds.

Remove and discard the hard rind and thick layer of fat attached to the rind from the Chinese bacon. Cut into very thin slices cross-wise. In a small bowl, combine the soy sauce, rice wine, and sugar; set aside.

Heat a 14-inch flat-bottomed wok or skillet over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add the vegetable oil and garlic, and stir-fry 15 seconds. Add the Chinese bacon and stir-fry 30 seconds. Add only the broccoli stalks and stir-fry 1 to 1 1/2 minutes, or until the stalks are bright green. Add the leaves and continue stir-frying 1 minute, or until the leaves are just limp. Swirl in the soy sauce mixture and continue stir-frying 2 to 3 minutes, or until the vegetables are just tender but still bright green. Serve immediately.

Serves 4 as part of a multicourse meal.

Braised Taro and Chinese Bacon

Lop Yok Mun Woo Tul

Taro root has the same starchy quality as a potato, but the flavor is more unusual, sort of like a cross between a potato and a chestnut. It is a cylindrical root, about 6 to 10 inches long and about 3 to 4 inches wide. The skin is dark brown, hairy, and dusty. It is an earthy and humble ingredient and, when cooked with wet bean curd and Chinese bacon, the flavor becomes dense and rich, It is food for the soul, especially in cold weather. For some people, the outside of the taro root can be irritating to the skin, so it's always a good idea to wear rubber gloves when handling it. See Nom Yu Spareribs for information on wet bean curd.

One 3/4-pound taro root

4 ounces Chinese Bacon(lop yok),store-bought or homemade

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

2 cubes red wet bean curd(nom yu)

1 scallion, cut into 2-inch lengths

1/2 teaspoon sugar

Wearing rubber gloves, peel the taro root with a cook's knife. Cut taro root lengthwise into quarters, then cut crosswise into scant 1/2-inch-thick slices. Remove and discard the hard rind and thick layer of fat attached to the rind from the Chinese bacon. Cut crosswise into scant 1/2-inch-thick slices.

Heat a 14-inch flat-bottomed wok or skillet over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add oil and bacon, and stir-fry 15 seconds. Add bean curd and taro, and stir-fry 2 minutes, breaking up curd with a spoon. Add 1 cup boiling water and bring to a boil over high heat. Cover and cook 3 minutes. Stir in the scallion, reduce heat to medium-high, cover, and cook 5 minutes. Reduce heat to medium, stir mixture again, cover, and cook until taro is just tender when pierced with a knife, about 5 minutes. Stir in sugar and serve immediately.

Serves 4 to 6 as part of a multicourse meal.

Stir-Fried Long Beans with Red Bell Peppers

Chow Dul Gock Hoong Ziu

For the Cantonese, Chinese long beans are the only vegetable a woman is permitted to eat the first month after childbirth. Vegetables in general are said to be too cooling (too yin), but long beans are neutral -- neither too yin nor too yang. Long beans are only available in Chinese produce stores and can be either dark green or pale green. The dark green beans are preferred by my family, as the texture is crisper. The beans are about 18 to 30 inches long and should be unblemished.

8 ounces Chinese long beans

1 large red bell pepper

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon sugar

Wash the beans in several changes of cold water and drain thoroughly in a colander until dry to the touch. Trim the ends and cut the beans into 2 1/2-inch sections. Wash the red pepper, then stem, seed, and cut into slivers.

Heat a 14-inch flat-bottomed wok or skillet over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add the oil and beans, and stir-fry 1 minute. Add 1/4 cup boiling water. Cover and cook on high heat 3 minutes. Add the red pepper, re-cover, and cook on high heat 1 minute. Add salt and sugar, and stir to combine. Serve immediately.

Serves 4 to 6 as part of a multicourse meal.

Long Bean Stir-Fry

Chow Dul Gock Soong

Mama and all her siblings attended boarding school in China. Returning home for the weekend, they would complain of the horrible food at school. So on Sunday nights each child would be sent back to school with two big jars of this stir-fry, meant to supplement their meals for a few days. Instead, Mama's two jars would be completely finished by the end of Sunday night! This stir-fry has a wonderful balance of sweet, piquant, and spicy flavors and textures. See Stir-Fried Long Beans with Red Bell Peppers for information on Chinese long beans(dul gock).

8 Chinese dried mushrooms

1 bunch Chinese long beans, about 12 ounces

2 ounces Sichuan preserved vegetable, about 1/4 cup

1/2 Chinese sausage(lop chong)

2 ounces pork butt

1/2 teaspoon salt

2 teaspoons thin soy sauce

1 1/2 teaspoons Shao Hsing rice cooking wine

1 teaspoon sesame oil

1/4 teaspoon ground white pepper

3/4 teaspoon sugar

4 tablespoons vegetable oil

1/4 cup thinly sliced scallions

1/4 cup cilantro sprigs

In a medium bowl, soak the mushrooms in 1/2 cup cold water for 30 minutes, or until softened. Drain and squeeze dry (reserve the soaking liquid for use in soups). Cut off and discard the stems and mince the caps.

Wash the long beans in several changes of cold water and drain thoroughly in a colander until dry to the touch. Cut into 1/4-inch-long pieces to make about 3 cups.

Rinse the preserved vegetable in cold water until the red chili-paste coating is removed and pat dry. Finely chop to make about 1/3 cup. Chop the Chinese sausage into 1/4-inch pieces. Dice the pork into 1/4-inch pieces and sprinkle with 1/4 teaspoon salt. Stir to combine and set aside. In a small bowl, combine the soy sauce, rice wine, sesame oil, pepper, 1/2 teaspoon sugar, and 1/8 teaspoon salt; set aside.

Heat a 14-inch flat-bottomed wok or skillet over high heat until hot but not smoking. Add 1 tablespoon vegetable oil, sausage, and pork, and stir-fry 1 minute. Transfer to a plate. Add the 1 tablespoon oil and mushrooms to the wok, and stir-fry 1 minute. Add the remaining 1/8 teaspoon salt and remaining 1/4 teaspoon sugar, and stir-fry another minute. Remove the mushrooms from the wok and add to the sausage mixture. Add the remaining 2 tablespoons vegetable oil and the green beans to the wok, and stir-fry 1 minute. Cover for 20 seconds. Uncover, add 2 tablespoons water, and stir-fry 10 seconds. Cover and cook 30 seconds. Return the sausage mixture and the preserved vegetable to the wok along with the scallions, cilantro sprigs, and soy sauce mixture. Stir-fry 1 to 2 minutes, or until the vegetables are just tender. Serve immediately.

Serves 4 to 6 as part of a multicourse meal.

Copyright © 1999 by Grace Young

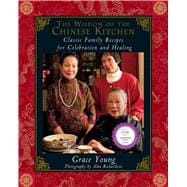

Excerpted from The Wisdom of the Chinese Kitchen: Classic Family Recipes for Celebration and Healing by Grace Young

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.