What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

When I was a small child, Walter and Rebekah Kirschner, my mother’s parents, were my favorite people in the world. They were kind and generous and interested in what their young grandson thought about things. Visiting them in Philadelphia at their big house on Carpenter Lane—my grandfather was a retired carpenter, and he lived on Carpenter Lane, a bit of serendipity that I found marvelous—I would go to bed late, usually after my grandfather and I had watched an 11 P.M. rerun of Benny Hill on the snowy UHF channel, and rise early. Coming downstairs in the morning, I would find my grandmother in her housecoat, leaning forward in her seat at the kitchen table, her big, thyroidal eyes scanning the morning newspaper from behind large plastic frames. Approaching from behind, I would hug her around the neck; without looking up from her crossword puzzle or word jumble, she would say, “Good morning, lover.” (That old-fashioned, noncarnal sense of the word has all but been lost, but my grandmother refused to abandon it.) The kitchen smelled of coffee, soft-boiled egg, and toast; my grandfather was somewhere on the grounds doing his gardening or, if we were in the fallow months, working with wood in his garage or basement.

More than the smells—of the seedlings my grandfather was planting, of sawdust, of coffee in the kitchen, of yesterday’s perfume still lingering about my grandmother’s neck—I remember the sounds of Carpenter Lane. Classical music was always on the hi-fi, as my grandfather called it. The dial was set to public radio, which in those days mostly played music (my grandparents were part of that small, now forgotten column of people who mourned as news and talk shows slowly pushed aside their music on NPR). When he heard a piece that displeased him, something too modern or atonal, my grandfather would switch off the radio and put on a vinyl record of Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra. For decades my grandparents went faithfully to the Academy of Music to hear those concerts, even after Ormandy gave way to Riccardo Muti as conductor. Toward the end of his life, my grandfather began to acquire compact discs, but he never played them, and it’s the warm sound of vinyl, with its intermittent pops and scratches, that I remember.

The sounds of their home, the aural landscape, comprised not just music but words, carefully chosen. My grandparents spoke a kind of English that one hears less and less today. They rarely raised their voices, they spoke slowly, they spoke with care. My grandfather had been raised speaking Yiddish, and my grandmother had grown up with a mix of German and accented English, but when they spoke English it was with the General American accent, the Ohio or Nebraska sound that television newscasters are trained to use. A practiced ear could hear a slight trace of Philadelphia in the way my grandfather said “merry”—it sounded like the name “Murray”—but in general he spoke like a college graduate from Anywhere.

My grandfather was one of eight children, my grandmother one of ten, and all their siblings had good grammar and literate vocabularies, but my grandparents had higher standards than that. My grandparents were old socialists to the core, believers in rule by the masses, but that did not mean they believed in speaking like the masses. One might say that they were Leninists, insofar as they believed that there had to be an educated vanguard to lead the people to revolution. Perhaps. But it would be more accurate to say that in addition to being socialists, they were snobs.

It’s not an unusual combination, or even an unexpected one, leftism and snobbery. When my grandfather graduated from high school in 1929, he found that many of the people he met who shared his interest in books and the arts, especially among fellow Jews, were members of the Communist Party. Communists read, and they talked about ideas, and they had theories about the place of art in the world. They read Dreiser and Dos Passos and Steinbeck, then argued about which ones had good politics and which ones’ politics were damnable. To these Communists, culture mattered. For my grandparents, then, being a Communist was a way of being learned, and it was also a way of being unusual, being more than just another working-class Jew.

But there was also an ethical dimension to my grandparents’ snobbery. When so many people don’t have the schools they deserve, when there is so much illiteracy in the world, what kind of ungrateful person would refuse the lessons of a good education? If you’re fortunate enough to have good teachers, or to have been exposed to books, it’s incumbent upon you, they believed, to use what you’ve been given. And only the worst kind of ingrate would put on uneducated airs, as a pose—that was like spitting on your schoolteachers’ hard work. If my grandfather had ever met a folk-singing wannabe who affected a hobo’s background, a troubadour of the ersatz–Woody Guthrie school, he would have been bemused.

That’s not to say that my grandparents spoke the Queen’s English. In one of those perverse twists of snobbery, they also looked down on people whose affectations ran in the other direction, too fancy. My grandmother always said that she didn’t like the way that her friend Adele Margolis said “foyer.” “It’s not foy-ay,” my grandmother would insist aloud, after a visit with Adele. “We’re not in France.”

My grandmother, in particular, had an explicit belief in language as the backbone of a civil society. She wrote letters. She called people on the telephone to ask how they were doing. She made social calls on her neighbors. She believed in social intercourse, and for that one needed language, preferably well spoken and adhering to certain agreed-upon rules. One morning I came downstairs to find her at the kitchen table in her housecoat, not working on a crossword puzzle or a word jumble but writing a letter.

“Who are you writing to, Grandma?” I asked.

“Whom,” she said, a little disappointed that by age ten I had not yet mastered the object pronoun. Her tone was kind, however, and I knew not to take it personally. She only corrected her children and grandchildren, the people she felt closest to. “I am writing to Vincent Fumo, my state senator. It’s about our license plate.”

“What’s wrong with your license plate?” I asked. “Did it fall off?”

“Not my license plate. Everyone’s. The motto on it reads YOU’VE GOT A FRIEND IN PENNSYLVANIA. But that’s not correct. It should be YOU HAVE A FRIEND IN PENNSYLVANIA. The got is unnecessary. I’m writing to him to say that they should change it.”

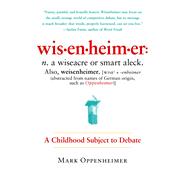

That was morning activity in my grandparents’ house. Whenever I wonder where I get my love for language, my close attention to it, my deep investment in it, I think about my grandmother bent over a piece of stationery, demanding that her state senator change the Pennsylvania license plate. I wasn’t the first wisenheimer in my family.

I’m not even the second.

My mother also has very particular views about language. Like her mother, she would never say foy-ay. In fact, whenever anyone on television does say foy-ay, she says, “My mother always hated it when Adele Margolis talked like that.” I’ve never met Adele Margolis, but I can never hear any French pronunciation come from the lips of an American—foy-ay, oh-mahzh (homage), ahn-deeve(endive)—without thinking about my grandmother’s occasionally snooty frenemy. My mother also has a particular objection to non-Jews using Yiddish words, to the point that she once got annoyed with a Gentile friend who printed an invitation to her “40th-birthday shindig,” until I pointed out to my mother that shindig was not a Yiddish word. “Well it sounds like one!” she said. (Of course, my mother is right to take exception to the locution of another friend of hers, a WASP from Greenwich, Connecticut, who talks about her husband’s “chutz-pah,” with the accent on the second syllable.) My mother is sensitive about the pronunciation of her name, Joanne, which she pronounces with a somewhat broad a—not quite Jo-ahn, but getting there—and won’t allow to be pronounced with the accent on the first syllable or with any nasal action on the second. And she can’t abide the word girlfriend when used with a nonromantic connotation. If my younger sister wanted to give my mother a coronary, she might try saying, “Me and a couple girlfriends are going to get a manicure.” I once asked my mother where she got that prejudice against girlfriend, and she said that her mother had frowned upon the word. “I used it once, and she said to me, ‘We don’t talk like that.’”

Who did talk like that? The residents of South Philadelphia, for one thing. My grandparents didn’t approve of American Bandstand, which adolescent girls all over Philadelphia watched on TV every afternoon, broadcast live from a studio on Market Street. “If my father saw me watching it, he would say, ‘Now why don’t you turn that off,’” my mother once told me. “The primary thing was, it was TV. But he also didn’t approve of those girls, with their teased hair and their pencil skirts. And he thought they must cut class at the end of the day to get to the studio on time. Why weren’t they home studying? That’s what afternoons were for, or for French club or Spanish club. My mother didn’t approve of the way they talked. When they did the roll call, the girls would get up and say, ‘Annette, South Philly.’ My mother would say, ‘We don’t talk like that. It’s South Philadelphia.’”

In my earliest years, then, the importance of language was all around me. It was there implicitly, in the careful way my elders spoke, and it was there explicitly, in their pronouncements and harrumphs of disapproval. Yes, this was snobbery. My parents did try to keep the snobbery within the family. We were taught from a young age not to correct other people’s speech, so that we wouldn’t be perceived by friends or neighbors as elitists. And doesn’t every family have its snobbery? The happiest, most close-knit families are close-knit because they have a culture of the family, a sense of the particular traits they share. Some families are musical, others are good at tennis, or especially pious, or perhaps just unusually numerous (I could write a whole other book about being the eldest of four children). For our part, we talked a certain way.

When I think about my grandmother, who died when I was fifteen, or about my grandfather, who died recently at age ninety-five, I think about their language. I can hear my grandfather talking about his friend Joe Ehrenreich, always carefully pronounced “Ehrenrei chh,” with the German fricative against the back of the throat. I can hear his overly correct pronunciation of the great Philadelphia river, the Schuylkill, which most Philadelphians call the Skookil—no first l, the whole word pronounced quickly—but which he languorously, luxuriously called the School-kill: “I love to see the houseboats lit up at night on the banks of the School-kill,” he said. I miss hearing him talk that way. Nobody else makes the river sound so beautiful. Except, now that I think of it, my mother.

© 2010 Mark Oppenheimer