The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

Wednesday, May 5, A.D. 1886

Fort Whitley, Kansa Territory

Captain George Armstrong Custer, Jr., looked back over his shoulder, toward the fort's main gate. The cold breeze of early morning smelled of the waters off the Gulf, only a few miles distant.

Fort Whitley's tiny barracks were two hundred yards away, and its timbered walls enclosed the largest yard of any fort in America. Nearby, a table and two rows of chairs stood untenanted, looking lonely and out of place in the midst of such spaciousness. The space was necessary for their work, though, as Fort Whitley was not a simple frontier fortification, not just a lonely link in a chain that stretched out into hostile territory. Fort Whitley, as George liked it put, was where they built the future.

"Still no sign of him," Elisha said.

"He'll be here," George replied. I hope, he added to himself. The knot in his stomach twisted a turn tighter and he turned back toward the yard.

The wind grabbed the doors to the oversized barn and pulled them against the blocks that held them open. Men in blue struggled against guy ropes that hung from the huge construction, then tramped through the barn's doorway and into the mud, pulling their prize out of the hangar and into the morning wind.

The breeze freshened and the soldiers dug their heels into the soggy turf. One man slipped on the dew-wet grass and slid forward on his rear. Derisive laughter was cut short by a bellowed command.

"Stand to, you bastards," Sergeant Tack shouted. "This is no time for games."

Elisha chuckled. "As if Tack ever allows that there is a time for games."

"Oh?" George said. "You forget poker."

Elisha's smile broadened. "Ah, but I didn't, sir. To Tack, poker is not a game, but a business."

The two officers shared a laugh and watched as the sergeant put his men back under control. The subject of their labors hung in the air above them. George looked up as its midsection emerged from the barn.

It was huge--taller than a house and over a hundred feet long. The cigar-shaped frame was made from steel and the new metal known as aluminum. The white fabric that stretched to cover it shone in the morning light, making the craft look like some odd, symmetrical cloud lassoed and brought to Earth. Beneath its bulk, attached like sucker-fish to the belly of an airborne whale, hung the cabin and engine cars. Cabling from the dirigible's sides helped support the cars and steering vanes, and it was these wires that sang in the damp morning wind.

George had fought hard for this contraption. He had pushed for its acceptance, had battled for its commission, and had overseen its construction. It was the child of his own work and that of his friend, Ferdinand, an obscure German count who had worked for the Union during the Civil War. Their discussions, with minor modifications and the application of American resources, had created the two things George had sought.

First, the craft would provide the Army with an edge in its "conflict" with the Cheyenne Alliance.

Second, it would provide George with a way to establish his name as his own, instead of simply being known as the son of his father.

"This is the future," George said as he stared up at the recalcitrant craft. "No more horses and sabers for the Army. From this day forward we will rely on men and machines to lead us to victory."

Elisha shrugged. He flipped up the collar of his blue wool topcoat and held it close against the chill breath of spring's memory. "If you say so, Captain. For myself, though, I just don't see the generals lining up for a ride in this behemoth, or turning in their fine stallions for one of those steam-driven carriages."

George tried to envision his father in one of the fanciful Benz carriages instead of on Vic or Dandy and smiled at the image. He took a deep lungful of air and released a frosty breath. "You are right. There's just something refined about sitting a horse that mechanical engines cannot replace. But horses are useless against the Cheyenne."

Elisha looked as though he might have argued that point as well, but the sound of voices from the direction of the gatehouse drew his attention.

A squad of soldiers on horseback rode in from beyond the gate into the yard. They were followed by four open carriages with high-seated drivers like in the days of Lincoln. The dignitaries--senators and a few representatives who had come to view the official launch--sat in the high seats and craned their necks for a better view of the huge aircraft. Behind the carriages were more riders, but not enlisted men. These were old men, most portly, all but one wearing the dress blues of the U.S. Army.

The one rider who was not in uniform wore a long topcoat of dark wool, buff-colored riding pants, and a high-collared shirt with a cravat of watered silk. From beneath his high statesman's hat flowed his trademark: locks of golden hair, now paling with age. It was George's father, the Boy General, Hero of the Civil and Mexican Wars, and the Savior of the Battle of Kansa Bay. Colonel George Armstrong Custer, Sr., President of the United States of America, laughed with the generals and congressmen as they rode into the yard beneath a clear, crisp morning sky.

Men ran across the yard from the barracks. They assembled near the barn with a great deal of cursing and clattering of equipment. Custer brushed at his mustaches and beard with a gloved hand as they rode toward the ranks. His eye glanced toward where George stood with Elisha, but he did not acknowledge his son. The clenched fist in George's stomach, rather than relenting at his father's arrival, only gripped him the more.

Colonel McCormack, commander of the remote outpost, stepped before the small detachment. He saluted his commander-in-chief and was rewarded with a tip of the presidential hat.

Custer dismounted, followed by the generals who did the same although with less agility. The statesmen all debarked. A few soldiers were dispatched to stable the horses and unhitch the teams. The guests moved to the empty chairs. They milled about, chatting with one another, but did not settle into the chairs provided them. McCormack stepped to the table, pulled a sheaf of paper from his coat pocket, and cleared his throat.

George heard Elisha groan. "Please," the young lieutenant said. "No speeches."

McCormack was preempted, however, when Custer walked up and shook the colonel's hand, engaging him in friendly exchange.

"God bless the president," Elisha said. George hid a smile.

At forty-six years of age, George's father made an imposing figure. With a confidence born of two decades of command, he walked slowly toward the dirigible as he conversed with the officers and senators.

"My lord, but it's big," George heard his father say as they strolled closer. "Bigger than I'd imagined."

George and Elisha raised hands to salute as the president and their colonel drew near. The colonel touched his brim, releasing them. The president squinted.

"Tell me again why these savages won't just shoot you down and feed you to their lizards?"

"Sir," George replied. "We will be too high for them to do any damage."

"I see." Custer was obviously unconvinced. He turned to the colonel. "And they've flown it successfully?"

McCormack straightened. "Absolutely, Mr. President. Several times, sir, and each time better than the last."

"So, they haven't crashed the thing in what? Four months?"

"Five, Mr. President." McCormack smiled with pride. George winced. He knew his father. While the colonel beamed at having exceeded the president's estimate, George knew that the question had been designed to point out the fact that there had been even a single crash.

"Colonel McCormack, let me put it thusly. Four months, five months, a year; it makes no difference. Anything less than perfection is substandard. Is that clear?"

The colonel's ruddy cheeks paled and blushed at the same time. "Yes, sir," he said.

George stepped forward. "Sir, I was in command of the ship when we ran into trouble. The fault for the mishap is mine."

The tall, lean Custer looked down at his son with the look of stern regard that George and his sisters had come to call "The Official Glare." It usually preceded what his father considered a bon mot of common sense.

"The fault may be yours, Captain, but the responsibility is still the colonel's."

"Yes, sir," George replied and stepped back.

"Mr. President," McCormack said, having regained his composure. "If you and the other gentlemen care to join me, we can review the plans for the dirigible and for its mission while the men prepare for its departure."

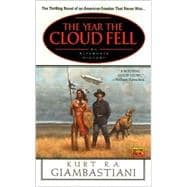

Kurt R. A. Giambastiani

The president smiled and nodded, once more the Spirit of Geniality. The colonel led the way.

Elisha humphed. "How are you, Son? Good to see you, Son. You're looking well, Son." "That will do, Lieutenant."

"I'm sorry sir. It just seemed that a little 'hello' wouldn't have done the old man in."

"I said, that will do." George took a deep breath. "Remember that he is here as the president, not as my father."

"Yes, sir."

"It's not a family reunion."

"No, sir."

"It's an historic military operation." "As you say, sir."

George ground his teeth, not sure what infuriated him the more, Elisha's studied deference or his fa ther's complete lack of parental warmth.

"Ah," George bristled. "To Hell with you both. Sergeant Tack!"

The men wrestled the dirigible to its mooring spire. George and Elisha--along with Private Lescault, who would act as their fireman--climbed up the ladder to the pilot car to begin their check and recheck of every operational aspect of the huge machine. Elisha and Lescault concentrated on the boiler and engine apparatus. George climbed up into the belly of the beast to inspect the superstructure from within.

The beam from his candle-lamp pushed up through the humid gloom. The danger of an open flame in a lighter-than-air craft had been greatly limited when George replaced the German count's design for hydrogen with American-supplied helium. Still, though, George took great care with the lamp. The internal bags were flammable, as was the fabric skin.

The ladder led up to the catwalk that ran the length of the aircraft like a spine. Gas-filled bags pressed up against the dirigible's internal skeleton of steel and priceless aluminum, holding the whole of it aloft. Sun

THE YEAR THE CLOUD FELL

light struggled in through the fabrics of skin and balloons. It shot through the needle holes of the outer seams, filling the interior with odd linear constellations.

George paced slowly down the catwalk. The walkway rang like an ill-forged bell. His gaze sought evi- dence of a wrinkled bag or stretched seam. His fingers plucked the cables, searching for the string out of tune. He checked the water levels on the ballast tanks that lay underneath the catwalk. The air smelled of dust and grease and sooty welds, and now and again the whole structure would grumble and turn on its mooring pin as the wind settled into a new quarter.

Inwardly, he kept coming back to the spot rubbed raw by Elisha's words of reproof against his father. "The General," as his father was often called--though he'd only risen to the permanent rank of colonel--had always been a complicated man, and one not well- suited to fatherhood. George was of the opinion that he confused his father nearly as much as his father returned the favor. The situation was different with regards to Maria and Lydia. Upon one's daughters it was not unmanly to dote. With a boy, however, his father's parental instincts quarreled with codes of military and social conduct.

The clang of his boots on the catwalk reminded him of a day long ago when he had caught a glimpse behind the tough faqade.

In his memory, a hammer rang on an anvil as the smith put the proper curl into a horse's shoe. George stood as a young boy in the smithy of an Osage outpost. The General stood next to him and explained the workings of bellow and forge to his son. George, still blinking in the sudden shade after the hard light of the Ozark summer, took a step closer to see better the breathing, fiery beast that inhabited the farthest darkness of the shop. Smoke, heat, and the volcanic smell of hot metal filled the air.

From his left came a sound. He turned. The horse's foot caught him in the chest and sent him through the air to crash against the wall amid tools and bar iron. The pain was sharp. The fear that washed over him was cold. His heart labored and his skin was too tight. Then his father was there--The General. Tears built in the boy's eyes as the realization of what had happened took shape. His father grabbed him by the shoulders and looked him up and down. The smith stood behind him, iron glowing in his tongs.

"Is he all right, sir?" the big man asked.

George's father swallowed and blinked. Then he untied the kerchief from around his neck and gave it to George.

"He's all right," Custer said. He stood and held out his hand.

George took the extended hand and was pulled upright. He sniffed and wiped at his face with the kerchief. Blood from his nose stained the blue cloth black.

"It takes more than a horse's kick to keep a Custer man down, eh, Junior?"

With a nod, George gave the only acceptable answer to such a question. Slowly, he accompanied his father back into the glare of the Missouri coast.

The hatch to the pilot car clanged open, bringing George back to the present. "Are you ready for a steering test?" Elisha called.

"Go ahead," George called from the rear. "Left side first. Then right."

"Your left?" Elisha said. "Or my left?"

"Aw, Hell," George said beneath his breath. The Army, in a prideful attempt to purge from this project any possible connection with the Navy, had decreed that all terms such as "port" and "starboard" were not under any circumstances to be used. As a result, George had lost count of the times he and Elisha had had this selfsame conversation.

"You know what I mean," George bellowed in mock exasperation.

"Aye-aye ... I mean, yes, sir!" his lieutenant said.

The long drive chains began to rattle as the boiler built up steam. George checked the connections down the length of the interior. Then he opened one of the observation doors in the dirigible's side and peered forward at the wide-bladed propeller turning slowly on its shaft. Behind, rudder and stabilizer panels moved through their range and back to a neutral position. George scuttled over to check the action of the opposite side. Everything was working as expected.

The belly of the aircraft began to fill with sound as the rotors picked up speed. The chatter of the chains grew into a smooth, deep-throated roar.

He checked the propellers again. The blades were now a whirling circle of translucence and the wind that they created made him squint. He shut the doors and made his way back to the pilot car.

"No problems," he said as he released his grip on the ladder. "It all looks good. How are things up here?"

Elisha finished his check of the instrumentation. "Looks fine." He turned toward the door to the engine car. "Lescault!" he shouted. "How is the engine behaving?"

"Good as gold, sir," came the reply. "Good as gold."

"We're ready, Captain."

George stood at the car window and looked down. The sergeants of the outpost again gathered the men into ranks near the mooring spire. The officers and senators emerged from the front door of the colonel's house and began to make their way across the boot-high grass.

"They're coming to see us off," he said.

"Well, sir, you'd best get down there."

"Don't want to disappoint, do I?"

Elisha smiled and George was glad they'd been able to melt some of the frostiness that their earlier words had created. He pushed open the car door and dogged it so it would not swing freely. Then he grabbed the railings along the jamb and swung himself out and onto the wooden rungs of the rope ladder. It was not a long descent--perhaps twenty-five feet--but it was precarious. He didn't want to slip and fall into the mud at the feet of the dignitaries. Therefore, he took a little longer than usual and stepped to the ground just as the guests arrived from across the yard.

At a bark from Tack, the ranks snapped to and stood tall. George gave salute once more to his colonel. "The United States Army Aircraft Abraham Lincoln is ready for active duty, sir!"

McCormack stepped forward and cleared his throat. George, fighting the urge to look up to the pilot car, stayed at attention. There was no rescue for them this time. Even his father would not be so rude as to step on this moment of commander's prerogative. McCormack faced the assembly.

"Today," he began, "is a day on which history shall be made. Today, the Union once again sets forth to claim the territories that are rightfully hers. For over one hundred years ..."

The breeze freshened and the dirigible groaned on its mooring, echoing George's opinions. McCormack droned onward.

In time, it was done, and the colonel invited the president to address the troops. Custer stepped up beside the colonel. He stood straight, proud, supremely confident.

"I would like to extend my thanks to the commander, the officers, and the fine men of this outpost. What you have achieved, what you have created, is nothing less than remarkable." The senators applauded these words and the generals followed suit. "And to the men who will drive this amazing machine, remember that as you pass over and into the untamed lands of our great nation, our prayers go with you. Good luck, and Godspeed."

Again the guests applauded. Custer turned and walked over to George with a smile.

"Get a good look at them, Son. Find out where they are and how many they are so we can know where and how hard to hit them. The Frontier is too big for us to run around looking for them. Understood?"

"Yes, sir."

The look in his father's eye softened a bit. "And be careful, Son," he said, extending his hand. "Your mother worries so."

And you do not, George thought. But when he clasped his father's hand, he felt the thinness of the bones within it. His father's cheeks were gaunt beneath eyes of cornflower blue, and his long hair was nearer to white than blond. The office and the Union's reconstruction after two terrible wars had taken their toll on the Savior of the Battle of Kansa Bay.

"Tell her not to worry," George said. "I just wish we'd had a few minutes to talk."

"Plenty of time for that. After the mission. I'll have the band play `Garry Owen' when you ride back into camp."

George nodded, stepped back, and saluted a final time. Custer returned it with a wink, and George turned and grabbed the ladder. Climbing up, he smelled the salt on the southwesterly breeze. Elisha reached out from the car and helped him inside. They pulled the ladder up and latched the door closed.

From the yard below, Tack's bellow echoed through the yard as he ordered the men to clear out of the way. George made sure the guests had all moved to safety before he opened the first ballast tank. Water streamed out from either side of the aircraft's midsection in a manner that was vaguely obscene.

"Thar she blows!" shouted one of the men from the yard. Tack yelled for silence. George pushed the lever shut, a mischievous smile on his lips.

There was no immediate sense of movement. Elisha raised an eyebrow. "More?" he asked. George shook his head.

"Wait."

Then, like a lumbering sea beast lifting itself off the shingled strand, a ripple moved through the craft as the nose began to slide up the spire.

"Forward thrust, one eighth," George said and Elisha turned the throttle lever to match the command. The pitch of the propellers changed and the blades bit the air. The craft shuddered once more and then slipped up and off the spire without another sound.

A cheer went up from the men below as the dirigible cleared its mooring. It floated upward. Inside, without any sense that it was they who were in motion, George felt the brief initial disorientation of balloon flight; the fleeting sense that it was the world that was dropping away and not the reverse. As the tip of the spire drifted below them, George gave the command for half speed. Elisha complied and George's brief vertigo disappeared under the craft's slow but perceptible acceleration.

He steered them to the north-northwest. "Give us some elevation, Lieutenant. Ten degrees."

Elisha manned the crank that controlled the pitch of the craft. As he turned the winch, cables ran up into the body and moved the counterweight that ran underneath the catwalk. The counterweight moved aft, and the nose of the craft lifted up into the sky.

George checked the bubbles in the attitude meters. "That's good," he said.

Now safely underway and climbing, he went to the open window. Below and behind them, the outpost was shrinking to a small square of mud and sedge amid the greater green of springtime. The men still in the yard were like lead soldiers, a tableau of wonderment watching the unlikely aircraft lift itself gracefully toward the clouds. George took off his cap. He waved out the window and the soldiers came to life, waving back. Behind the men in blue, he saw the dark figures of the statesmen, and the man with the long pale hair. He wanted the man to wave, too, but he knew he would not.

George squelched his own irrational annoyance and turned back to the task of guiding their course. The boiler let off a puff of excess pressure as they rose. "Tamp it down a bit, Private."

"Aye-aye, Cap'n," Lescault growled in answer. Elisha laughed, pointing at George's scowl of consternation.

"And after you worked so hard to make this an Army mission."

"I can see now that there's no point in continuing the struggle," George sighed. "All right. I admit it. It's a ship. Airship. Vessel. Whatever you like. Port. Starboard. Bow, and aft. It's a ship!"

"Huzzah!" shouted Elisha and Lescault together.

"I'll deny in public I said it, though," George told them. "And no one will ever believe the likes of you two."

They reached altitude and headed along the northeastern limit of the Gulf of Narváez. Shoals of fish flashed and spun in the warm, shallow waters below. Small, leather-winged cliff dragons sailed from the rocky breakwaters and dove for their silver-sided prey. George looked ahead. He and his small crew were flying toward a land full of things found nowhere else in the world; huge buffalo, giant lizards, and the American Indian.

On paper, the western border of the United States was a thousand miles distant, somewhere along the spine of a mountain range that only a handful of white men had ever seen. In reality, it was formed on the northwest by the Red, Sheyenne, and Missouri Rivers that limited the Santee Territory. In the south it was made by the Sand Hills and the coast of Kansa Territory along the Gulf of Narváez, that body of water that stretched up from the Gulf of Columbia into the heart of the North American continent. As the three men traveled north from Fort Whitley, they entered lands that had been purchased from the King of France two generations past, but which had never been explored, much less settled by their owners.

Long snakelike necks lifted out of the water as huge behemoths watched the passage of George's craft. The dirigible flew over long stretches of swamps and fens. The air smelled of salt and mud until they came to the dense forests of the Kansa coast. For miles the greenery of towering ferns hid the ground from their view, and George and Elisha could see only the sudden flights of birds that flashed in colors of pink and blue as the flocks took to the air.

As they left the forested rim of the Kansa coast behind them, George took a deep breath, anticipating the mission ahead of them.

"Welcome to the `Unorganized Territory,'" he said.

Elisha looked up from his navigation charts. "It does look rather disheveled," he said jokingly.

To George's eyes, it was beautiful. A few miles inland and over the heads of the coastal hills, the land presented itself slowly. The low folds of the Sand Hills gave way to a vast prairie that stretched on forever. The horizon was flat and unmarred, but as George sailed the A. Lincoln onward, the land developed features. Rises--they were too subtle to be called hills--lifted and fell beneath the ship. Rivers laced the landscape with silver ribbons. Forests of cottonwood and box elder lifted green-feathered branches above fern-lined creekbeds. Beyond, ahead of them like a placid sea, lay league after league of prairie grass at least knee-high and pale green with springtime growth. The rivers and even the woods wound and twisted lazily until they blended into the low curve of the land, but the prairie itself continued onward, onward to the horizon, where the green of the grass met the blue of the sky in a turquoise melding of heaven and earth.

George marveled at the sheer expanse of land. He picked a metal wedge out of the rack and snugged it in place against the spokes of the pilot's wheel. He let down a window and leaned out on the sill. The air was still cool but no longer fresh from the sea. He took a slow chestful. This was old air. It smelled of sweet grass, a touch of rain, and miles and miles of land.

In the forest below he caught sight of movement. The whole ship grumbled with the vibration from the boiler and pistons and chains, and the wind sighed through the wires and through the whirling propellers. Even above such noise, however, he heard the call of the animals that ran through the trees.

"Whistlers!"

"Where?" asked Elisha, crowding up along the sill. George pointed down to the forest edge.

On strong hind legs the large, lizard-like whistlers ran, fleeing the approaching noise and shadow of the airship. They ran from the trees and onto the freedom of the prairie. Tails held straight out behind them, front arms tucked in close, the whistlers ran with great speed. Their skin paled as George watched, shifting from shadowy gray to a brindled green that turned the running lizards into phantoms fleeing through the tall grass.

They ran away from the ship, outdistancing it easily with a mile-eating gait. He saw them roll an occasional eye backward to check on the threat. Their calls of warning trumpeted through the air, amplified by the long, bony crests that curved back from their heads and over their necks.

Then they disappeared. George and Elisha gaped.

"Where did they go?"

George went to the wheel, undogged it, and steered the ship in the direction they had last seen the flock. The ship turned and settled into its new course. He rejoined Elisha at the window.

As they neared the place where the flock had last been seen, George noticed something irregular in the grass far below.

"There," he said, pointing.

The flock, skin tone now a perfect match to the prairie grass, had stopped in their flight en masse and hunkered down to hide in plain sight. From above, the two men could see the slight splaying of grass, but from the ground they would have simply vanished.

"In all the world," George wondered aloud, "why do we only find these creatures here?"

Elisha bit off the end of a hard biscuit. "You only found horses in Europe," he said while he chewed. "Or in Asia. Weren't any horses here until the Spanish brought them."

"That's not what I asked," George said.

"No," Elisha agreed. "But no horses here. No giant lizards there. Answer one, and I bet you'll answer the other."

George shrugged. "Maybe," he said. "Maybe."

As the ship came over the beasts once more, turf flew as they bounded off. George let them go and returned the dirigible to its original course.

The door to the boiler room opened and Lescault entered the pilot car. He smelled of smoke and oil and sweat and was already sooty up to his elbows.

"You missed our first whistlers," Elisha said as the fireman opened the opposite window and leaned out into the cool breeze.

"Bah," said the private. He wiped his dirty face with a slightly less dirty kerchief. "I hate the beasts."

Elisha took a jug of water out of stores. "You've seen them before, then?" he asked, pouring a cup.

"Thank you, sir," Lescault said as he took the cup and drank it off. "And yes, sir. Seen 'em plenty. My grandfather was a trapper up north in Assiniboine territory. My mother and father ran a trading post of sorts just the far side of the Santee border. I've seen more than my fill of hardbacks and whistlers. Hardbacks can at least be put to a little use, but even they're a stupid, foul-smelling breed. Give me a good Penn's Sylvania dray anytime."

"And whistlers?" George asked, taking a drink himself.

"Worse than useless," Lescault answered. "Smart, to be sure. Too smart. And bad-tempered, too. Untrainable. Good for nothing, if you were to ask me. Not for eating. Not even for tanning their delicate hides."

"You've eaten whistler meat?" Elisha asked with a laugh of surprise.

Lescault nodded. "Once, sir. I was a boy and it was a terrible winter night. My pa heard one calling. Got separated from its flock in the storm, we figured. Stringiest, most rancid-tasting meat I've ever had." He took another drink. "No, I've seen enough of whistlers. Got to give the Indian credit, though, for getting any use out of them at all."

"Too much use," George said, looking back out the window. "My father used to say that, were it not for the whistlers and the walkers, he would have taken the territory in '76."

"Did you ever see a walker?" Elisha asked the private.

"No, sir, but I've seen what they can do. One night we woke up to a terrible racket coming from out in the barn. Pa went out with his rifle. We heard a howl and a shot and then Pa came back inside, wide-eyed and white as a new cotton sheet. Wouldn't let us open the door 'til morning. We lost a horse and the milk cow that night. A few weeks later we were heading for Penn's Sylvania. Pa never went back to the prairie."

"What about you, Captain? Ever seen a walker?"

"Once," he said, a bit surprised at the terse tone of his own reply. The men across the cabin remained expectantly silent but, "Just once," was all he offered them. He turned his gaze back out the window. The others replaced the water jug and returned to their duties.

"We've picked up a tail wind, Captain. We're making good time."

George turned but Elisha had anticipated his question. His calipers were already walking across the map.

"We should reach our first waypoint in about eighteen hours." The lieutenant looked up from his calculations. "If the information we have can be trusted, of course."

George nodded. "How long until we reach the edge of our charts?"

"Ten hours. Around dawn."

"Well, we couldn't have planned that better. We'll have the whole day for charting. Let's take the speed down a notch. I don't want us to overshoot our maps before daylight."

"Yes, sir."

George pulled out the telescope. Feeling more like a privateer than an officer in the U.S. Army, he scanned the vista.

There was no sign of habitation. No homesteads, no Indian camps, not even a lone rider. They were alone on a hostile sea and sailing toward the limits of their knowledge. For four years, it had been the only subject of George's dreams.

The reality made him queasy.

Beyond the warm lamplight of the lanterns, the night was a void roofed with a million pinprick diamonds. The light of the waning moon lit the dark land like pale gossamer; a dream laid out beneath them.

The crew were to spell one another throughout the night. At such a lazy cruise and with the weather retaining its mild countenance, the Abraham Lincoln required little attention. Only the occasional shovel of coal or adjusting touch to the trim was needed. Elisha and Private Lescault got their rest. When George's turn to sleep came, he let it go. Uneventful though the evening had been, he knew that lying down to sleep would be a vain endeavor.

Instead, he watched the jeweled sky for shooting stars. He judged the ship's land speed by clocking the passage of ribbons of reflected starlight in the land below. He marked their progress on Elisha's maps. He nibbled on hard biscuits and dropped morsels out the window, watching them disappear into the depth of darkness like an ember into a nighttime pond. It was quiet and unexciting activity, but it kept him busy. Still, his heart leapt at the airship's every creak, and his breath grew light whenever he adjusted their course or checked the boiler, for it was at such moments that the magnitude of his responsibility was clearest: the first powered aircraft on its maiden voyage. His first real command.

As dawn approached, George became aware of an odd, recurrent sound. It would begin as a faint and infrequent groan--barely realized before it ceased--and he could not locate the source. Soon, however, the frequency increased and it grew into a consistent grumble of varying pitch. It was still faint, but it was definitely not his own tired imagination.

He nudged Elisha and Lescault awake and told them of the sound. "I'm going up to the bags," he said. "You poke around down here." He left them rubbing the sleep from their eyes and climbed the ladder up into the body of the craft.

The sound was less obvious up above. The chains rattled through their traces, the guys were all taut, and none of the gas bags showed any sign of damage. Even the ballast levels were consistent. All was as it should have been, and that did nothing but increase his trepidation.

"What else can it be?" he wondered aloud. If it was more pronounced in the cars, that would most likely indicate the boiler, but all the readings were fine when he had checked it.

He stepped down to the engine car. The sound was definitely louder here and, he believed, louder than it had been before. He walked forward to the pilot car and found Elisha and Lescault leaning against opposite walls, arms crossed, faces dour.

"What is it?" he asked them. "Do you know the cause of it?"

Elisha nodded. Lescault looked distraught.

"Well?"

"Over here," Elisha said. George moved closer as the lieutenant opened the window. The sound increased. It was coming from outside the car.

The day had dawned gray and cloudy. The sky--so clear at midnight--was a dark pall. Groans filled the air, even above the whir and chop of wind and propellers. He looked down.

And saw buffalo.

What he had thought was the lingering shadow of night was instead an immense herd of shaggy, hump-backed bison. They stood so thick in spots that he could not see the earth between them. The dirigible passed over them, creating a swath of panicked beasts, and it was their lowing that he had heard, even at such a height and above the sound of the engine. He had taken their calls of animal fear for a groan of mechanical doom.

George closed the window. He saw that the dour faces and even Lescault's teary eyes were not the signs of imminent disaster, but of laughter held in too long. With a shrug and the shake of his head, he released them. Their humor came out in gales.

"There," Elisha said, looking through the telescope.

George squinted into the gloom beyond the windows. The day had grown darker instead of brighter as the southwest wind brought heavy weather in on their rear quarter. This terrain was much different from the flat Kansa plain where they had tested their skills. Here it was a gray, folded landscape that hid its features from the unaccustomed eye. He could make no sense of it.

"Where?" he asked.

"There," Elisha said again and pointed. "The line of cottonwoods that runs out to the left. That must be where the White meets the Missouri."

George squinted again but his attention was taken by another gust that rocked the dirigible. He pulled the wheel to counter the wind and shook his head. "As you say, navigator. I'll just be glad to have our nose into this wind. We're scudding like a crab with it on our backside. Give me some speed, Lescault. We're going to head into it."

The private shouted his acknowledgment and the boiler roared as the firebox drafts clanged open. George pushed the throttle lever open to increase the pitch of the propellers. The ship shuddered again as another gust rolled around her girth.

The pilot's wheel was stiff, then loose, then stiff, all in a matter of seconds. George cursed as he pulled the wheel to port and reset the trim. The wind rippled across the grassland. Ahead, the line of cottonwood trees lashed and bent. Finally, he saw with his eyes what the lieutenant had been pointing to. In the middle of the forest was a band of foamy water. The White River rushed down out of the obscuring hills, its final run a rocky rush to confluence with the larger, wider, more stately Missouri.

The rolling of the ship eased off as the A. Lincoln put her nose into the wind. George relaxed his grip on the wheel. He checked the ground, some five hundred feet below. The trees slipped by beneath them, but in the wrong direction. The ship was pointing westward, but was traveling east, pushed back by the strong prairie wind.

"I need that speed," he shouted over his shoulder to the engine car.

"It's coming, Captain. Pressure is building now."

The tone of the engine changed, its regular thrum becoming more insistent, more urgent. The hiss and pop of the pistons merged into a long sibilant exhalation. The ship rang with the vibration. George felt it in his feet and through the wheel in his hands. Slowly, their backward progress reversed itself. The landscape crawled toward the rear and they were again underway, heading west above the White River.

The weather ahead of them did not look any friendlier. The sky was dark and low. Rain hung like veils from cloudy ramparts. Lightning winked and flashed across the belly of the storm.

"Damn," muttered George.

Elisha noticed, too. "What shall we do? We're barely making headway."

George did not like his options. It was a roll of the dice, no matter how he decided. Higher, lower, ahead, or back; there was no correct choice. He could only hope to give them the best odds.

"We surely can't get above it. If we anchor, we're a sitting duck for that lightning. The winds make it too dangerous to go any lower anyway. If we run before it, we'll be back in the States before we can turn around again. I say we ride through it from here, beneath the clouds but high enough to give us some breathing room."

"Very well, sir."

The men moved quickly to prepare the ship for rough weather. Loose items were stowed, cabinets were locked, and all doors and windows were secured. Then they were ready. Riding at full speed, the airship crept toward the onrushing stormfront.

The wind gusted. It wailed through the cabling and rattled the windows like a ghostly siren. Thunder rolled across the plain. Rivulets of water began to stream down the airship's sides. George looked at his gauges and saw them changing.

"Downdraft! Get to the winch. Pitch up, fifteen degrees. We've got to keep our altitude." He opened two toggles and pulled the ballast release. More water streamed downward as four petcocks opened in the ship's sides. The ship reacted slowly, but it did respond. He saw the nose lift. He held the ballast lever open a few seconds more and then pushed it shut.

Lightning blistered the air, and thunder shook their bones. The ship had started to regain some altitude, but not fast enough.

"Increase pitch to twenty degrees. Lescault, I need more power for the props."

Again the sky flared. The storm was atop them, battering down. Fat raindrops turned to hailstones the size of a man's fist.

Oh, Lord, George prayed. Help us. She wasn't designed for the likes of this.

They climbed up toward the belly of the clouds. George held the wheel against the gust. They rose quickly now. The ship groaned. He looked up the slope of their ascent.

The clouds above were streaking across their path. The ship was still sailing west, into the wind, but the clouds were moving to the south. The ship was climbing up into a broadside blast.

"Pitch down!"

"Captain?"

"Down! Now!" He slammed the steering vanes into a dive. "There's a crosswind above. If we hit it, we'll be torn apart."

The ship gave a second groan. This one ended in a sharp report and the whistle of a snapped cable.

"Oh, God," Elisha said as the floor slewed beneath their feet.

The forward half of the ship twisted as it was hit by the sudden air above. It rolled, and the floor now slanted to the rear and the left. Two more shots shook the airship. The nose deformed visibly as George watched, and the ship rolled another eighth-turn.

"Hold on!"

George grabbed the wheel. Elisha hung on to the winch pedestal. Lescault shouted blasphemy from the engine car and then the ship rolled some more. Metal wedges slipped from their coves and cracked the windows below. A cabinet door burst open and a water jug fell down and smashed against the portside wall. The windows looked down on the dark river and up into the darker clouds. To the fore, George saw the nose bend a third of the way down its length. The wind finally caught the tail and pushed the ship up on her head. The men cried out as everything twisted and pitched down to point at the ground. Lescault fell through the cabin, screaming. He burst headfirst through the windows and was silent as he fell in a squall of shattered glass down to the cold water nearly 500 feet below.

George gritted his teeth and held on all the tighter to the wheel.

Cannonshots sounded through the length of the interior; braces buckled all down the ship's spine. They were doomed now, he knew; a dead ship going down. Bags of helium burst with the hiss of mammoth snakes. As George lay sprawled across the pilot's wheel, he looked down. The ship had been blown back away from the river and now it was the ground that was accelerating toward them.

He said a prayer. He made it brief.

As the shadow of the ship came down to earth, Elisha and George shared a glance.

"Take care, Captain."

"You, too."

The nose of the airship hit the ground and crumpled. Crushed gas bags exploded and the skin of the ship blew outward with the escaping helium. Cables snapped and the engine car keened as it fell away from the ship, ripping out metal arms and chains like viscera. It crashed against the bottom of the pilot car, knocking George loose from his unstable perch. He hit the forward wall and grabbed on to the cabinet handles, the only thing within reach. Elisha had kept his hold on to the base of the winch. The body of the ship imploded as it drove into the ground. Bursting gas bags sent shards of metal flying. Glass shattered and the storm's thunder was transcended by the detonations.

George hid his head and curled into a ball around his feeble anchor. The pilot car was pulled away from the ship by the falling engine car. George's world turned upside down once more as both cars flipped over. The fore cables held a moment longer, slowing the descent, and then George saw the prairie grass come rushing upward.

It seemed an age, an aeon, between the time he tried to open his eyes and the time he actually did. When he finally succeeded, he saw a gray sky. He felt the light touch of drizzle on his cheeks. He felt the earth beneath him, and felt a hand beneath his head. He heard a voice, humming softly.

A face came into his view, and he saw a woman. Dark-haired and dark-eyed, she looked at him with concern knotted between her brows. It was she who was singing, ever so quietly. Her cheeks were broad and her skin the color of oak.

An Indian, he thought, and was afraid. The Cheyenne did not take prisoners. His briefing had been quite definite on that point. He struggled to rise, but she pushed him back down and shushed at him.

" Ecouté, ami ," she said. Listen, my friend. "You are wounded. Keep still."

George's French was rusty, and his skull was ringing. He tried to focus on the woman's face, but could not. She became a dark blur against the pale sky. His fear reached back into his mind and tried to form the words that he hoped would save him by making him more valuable as a prisoner than as a corpse.

" Je suis ... le fils de ..." He could barely think of the words. I am the son of-- He tried to think of the name the savages had given his father during his campaigns. Pieces of the word rattled around in his head, then came together.

"Tsêhe'êsta'ehe." Long Hair.

"I am the son of Long Hair."

Copyright © 2001 Kurt R. A. Giambastiani. All rights reserved.