The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

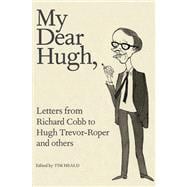

Introduction

Richard Cobb was unusual.

His public reputation makes him seem almost conventional. He was Professor of Modern History at Oxford from 1973 to 1984 before which he was a Fellow of Balliol for 10 years. He was amazingly knowledgeable about France and all things French but most of all about the French Revolution. He wrote several books about this, the first of which was in French and appeared in two volumes as "Les Armees Revolutionnaires". He was also a memoirist of brilliance who wrote several slim autobiographical volumes full of vivid and evocative scenes described in a style which was lucid, entertaining and unique.

The entry in Who's Who records his marriage to Margaret who was a pupil of his at Leeds University and of their five children. It mentions his education at Shrewsbury and Merton where he was a Postmaster. His ten years of research in France are listed together with his early academic career teaching at universities in Aberystwyth, Manchester and Leeds. There are honorary degrees, the Legion d'honneur - he was a chevalier - and a CBE. The publications are impressive and include one book which won the Wolfson History Prize and another which secured him the J.R. Ackerley. His address is given as Worcester College, Oxford where he held a Fellowship from 1973. He died in 1996. It sounds like a worthy, well-lived but essentially rather dull life.

None of this semi-official stuff provides much of a glimpse of the real self - "l'etonnant Cobb" as his many French admirers called him. He was an extraordinary man in many ways and although his qualities as a historian underpinned and bolstered his reputation and his achievements they didn't begin to tell the whole story.

His Frenchness was vital. One of the compliments he most treasured was when a Frenchman described him as "un titi Parisien" which meant, essentially,that he was "one of them". He spent many years in Paris, lodged as a young man in the rackety dixieme district of Paris, later had a flat in the Rue de Tournon and eventually, with Margaret, graduated to a house in Normandy which turned out to be one of several essentially disastrous forays into the property market. His ostensibly English writing was conducted in a curious upmarket franglais in which his mother tongue was liberally aided by French words and phrases. It was a style that was unique to him and perfectly encapsulated a personality which was as nearly bicultural as it is possible for an Englishman to be. And, in many ways, he was by education and background - his book on childhood Tunbridge Wells is an uncomfortable classic - the quintessential Englishman...

8 April 1981

The trip to the States seems to have been a success and at the beginning of April Cobb wrote to thank Wasserstein for his part in it.

'I got into Heathrow after a perfectly comfortable flight, part of it spent watching a film of quite unusual inaneness. England was looking very green, but now it is quite Arctic. I find myself thinking with affection of Brandeis, even of Steinbergers, of Waltham, of the Silver Bullet, and the young man in the cowboy hat who drives the 1.35 from Roberts to Boston…Here everything is boring & predictable.'

On 9 April Cobb wrote to Trevor-Roper

'I greatly enjoyed Brandeis, but Barraclough remained invisible. I really wonder whether he actually exists, as few people there claim to have seen him or even heard him on the phone; on the other hand, he is listed as having an address in Boston. Harvard I did not greatly like, at least the place, Cambridge; every square was crowded with earnest students SITTING DOWN in the dust and protesting about this or that, mostly somewhere called El Salvador, and there were horrible boutiques full of Mexicans, and more students on the banks of the Charles River playing (atrociously) guitars, and listened to by barefoot girls. The Faculty Club was rather more agreeable, I had lunch beneath a portrait of Frederick, Prince of Wales (Monster); and there was a lady at the next table wearing an enormous red hat that would have done quite well at Ascot. American students are so terribly literal, they made me feel utterly flippant; perhaps I am.

I went to a Balliol Gaudy on Saturday for 1900-1930. The Chancellor [Harold Macmillan] was there. I sat next to a Mr. Smith, who came up in 1917, and who is the son of A.L. Smith. In fact we sat right opposite his father's portrait which comes before that of Pink Lindsay. He said it was a very bad portrait, that his father would never have stood with his hands in his pockets, or worn a cardigan that did not match his coat. I think he was the Master's 9th or 10th child. Later I had a talk with the Chancellor, who seemed to be under the impression that I was Quentin Skinner and who talked to me most learnedly about Machiavelli; I did my best, that is not very well. He told me that before he gave away the Wolfson prizes in 1979, he had to read a boring little book about the Paris sewers and corpses, not at all "the broad sweep of history". I agreed meekly, not revealing that I was the historian of sewers and corpses. I think this was diplomatic. I left him , well after midnight, in full flow on the subject of Biafra. Tony Kenny told me later that he took him off to the Lodgings at about 2.30 a.m. At dinner, he gave a magnificent and tearful speech. All in all, a very good occasion. What I noticed was how good-looking were many of those old men. Class, I suppose. Before lunch I watched the boat race with Stacy Colman.a former classics master at Shrewsbury who was at one time (in the 30s) a Mods Tutor at Queen's. He is a rowing enthusiast; in fact the school Boat Club have named a boat after him. He used to row in the Balliol eight with Bill Coolidge, the homosexual millionaire and Balliol benefactor.

I was very pleased to see that horrible man Irving properly clobbered in the TLS.

I shall be coming over to the Fens some time this month to unload on the CUP an immense pave which they are not publishing, it is no good. About 1500 pages in typescript, it is called inappropriately The French Revolution in Miniature; and as the man is incapable of a joke, this is not a joke. It is in fact a study of a single Paris section. I shall drag it back to the Fens on the bus.'