The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Baby's Story

Just shy of his ninth birthday, my dog Blue lost a year-long battle with cancer, which had begun as a small melanoma on his lip and rapidly overtook his entire body. I couldn't bear to see him suffer. When the day came that he could no longer eat or muster the strength to go for a walk, I called the vet to come to our home. I was filled with angst about whether Blue had suffered too long already, or if he still had some good days left.

As he lay stretched out on the living room rug, very still and seemingly peaceful, I studied his magnificent profile before the doctor administered the injection that ended his life. Leaning close, I told Blue how much I loved him, and I thanked him for being my most important teacher. I was, and still am, filled with wonder that a member of another species taught me about unconditional love and the interconnectedness of all living things on this planet. Although my beloved Blue was certainly my first dog teacher, it was my second dog -- a three-legged puppy-mill survivor named Baby -- who exposed me to a world I never knew existed, one that would profoundly impact the course of my life.

At first it was hard to think of any dog replacing Blue, but several months after his death, I thought I might be ready to look for another. This time I wanted a small dog, one who could travel with me. I did an online search for toy poodles, which led me to an innocent-sounding website, where hundreds of breeders advertise. I spent hours reading the postings,oohing andahhing over all of the adorable pictures of pups for sale, never once suspecting that behind many of those innocent photographs was rampant abuse and unspeakable suffering.

I mentioned my search to a friend who worked in animal welfare, and she was horrified that I would even consider buying a dog from a breeder, especially one from an Internet site. And so began my education into the cruel world of mass dog production. Up until that time, the animal welfare topics that I had primarily been aware of were the inhumane methods of raising and killing animals in the food and fur industries. But I knew nothing about puppy mills. My friend tried to explain that dogs sold at pet stores typically come from inhumane breeding factories known as puppy mills, and that most commercial breeders -- no matter what they advertise -- are guilty of mistreatment. She tried to sell me on the idea of adopting from a shelter or a rescue group, but I'm ashamed to say that I only half-listened. All I could see were those adorable faces staring at me from my computer screen.

One breeder, in particular, sounded impressive -- he was based in Texas, and the picture he had posted of the most darling puppy clinched the deal. I called the number and put a deposit in the mail to him that day. To satisfy my curiosity, and hopefully dispel the worries of my animal-welfare friend, I decided to fly down to Texas to see the breeder's operation firsthand. After landing at the airport, accompanied by my friend Bryan, we rented a car, and about an hour later were parked at the end of a long dirt road that ran beside acres of flat land dotted by a couple of sheds and a house farther in the distance.

It was a Sunday, a fact I'll never forget because we had to wait for the man to return from church. (How ironic, given what we would soon learn about him.) As soon as we stepped out of our car, horrible sounds greeted us -- the desperate cries of hundreds of dogs barking from within the two wooden sheds. I felt a terrible sense of dread in the pit of my stomach, knowing this was what my friend had tried to warn me about.

The owner showed us into the smaller of the two sheds, which housed a couple dozen wire cages, a lone and frightened puppy in each one. These were the puppies for sale. The moment we entered, they all flung themselves against the sides of their barren cells, frantic to get out, except for one puppy who lay still and listless in the corner of his enclosure. The fear, loneliness, and deprivation were palpable, and overwhelming. This wasn't the warm and fuzzy, bucolic setting I had envisioned. This was a business, and to the mill owner these puppies were a commodity, no different than soybeans or metal widgets.

The racket from the larger shed next door increased as the occupants obviously sensed our presence. When we asked, we were told that the breeding dogs were kept in there. I couldn't bring myself to go in and asked Bryan to take a look. Minutes later he came out, his face grim. Later he would describe the misery he saw -- dogs crowded into cages, trampling each other to try to reach him as he neared, animals who have gone cage crazy, spinning endlessly, others who were gravely ill or severly maimed, some appearing to be near death, all with filthy matted coats covered with urine and feces that filled their cages, and the overpowering stench that made him gag -- the sights, sounds, and smells of torture and suffering.

Bryan glared at the miller. "You have all this land," he said, "don't you ever let the dogs out of their cages to run around?"

The man shook his head, explaining that he didn't want to be bothered with ants or insects getting on the dogs, or them running away, and that it was easier to keep them in cages all the time.

The idea of an animal being locked in a cage for years was so staggering to me that I felt my chest tighten in panic for them. Thinking money was the issue, I offered to write him a check on the spot to fence-in an area for them to get exercise. He declined. When we told him that we thought it was incredibly cruel, that the dogs were obviously going insane and suffering a horrendous existence, he shrugged and said, "They don't mind being locked up. Animals don't have feelings." He added that he had been inspected by the USDA and was told he had a "model facility."

I replied that if the USDA called this a model facility, the standards had to be changed, and that I couldn't, in good conscience, be a party to it by buying a puppy from him. Bryan, having been raised a Christian, and remembering that the man had been to church that morning, tried to reason with him on those grounds, reminding him that God and the Bible were clear about the need for humane treatment of animals. My own Jewish background taught the same. The man didn't respond to that, unwilling or unable to see anything other than dollar signs where these dogs were concerned.

We drove off, panicked and despondent over having to leave all those tortured animals behind, and aching for the thousands of others who, we now realized, were being abused by breeders across the country. I remember we were both so filled with helpless rage over not being able to take those dogs with us that we couldn't speak to each other for a while. I thought about buying every last dog and taking them all with me, but I knew the man would have restocked the cages with new breeding dogs within a week. I multiplied this mill times thousands that I imagined across the nation and felt a staggering sense of helplessness and despair.

In that instant I knew that this was a defining moment in my life, and that I would never be the same. I remember saying to myself, "Your life will never be the same after today." As I tried to come to terms with the horror that surrounded us, my only thought was:You must stop this. However long it takes, however much it costs, you must stop this.

I realized that this was an ugly secret being kept from the public -- and obviously supported by the USDA, which, I was to learn, fails to adequately enforce animal welfare standards in many industries. But I would also learn that the meager standards that are on the books are anything but humane: If a dog has food and water, she can legally be locked in a cage for years without the breeder being charged with animal abuse. How can we lock an animal in a cage for life and not call that an act of cruelty? This isn't how man's best friend is supposed to be treated, or any animal for that matter.

Such legalized abuse struck me as a travesty -- not only for the animals, but for the humans perpetrating it. By hurting these defenseless creatures, we are hurting ourselves just as much -- damaging not just our soul, spirit, psyche, or whatever you choose to call it, but our society as a whole, which becomes contaminated by this kind of legalized cruelty. If it's acceptable for a business to abuse animals, it makes it easier for us as a society to abuse the environment, the poor, women, minorities, children, or any voiceless and vulnerable group. I had come to understand that the abuse of animals wasn't an isolated event that can be shrugged off as a necessary evil, or an unavoidable by-product of big business. It's something that sends shockwaves through everyone and everything, from the factory farmer or the puppy miller to the consumer and even the investor who buys stock in an animal-abusing company. It promotes a culture of abuse and destruction that impacts the quality of our lives on every level.

In short, I realized that what hurts the animals hurts us -- not just morally and spiritually, but physically (as I would later learn, the cruel, factory-like conditions at livestock farms contribute more to global warming than all the cars, trucks, and planes worldwide).

As our car headed back to the airport, I broke the silence and vowed that I would do whatever it took to stop this cruelty, starting with rescuing a dog instead of buying one from a breeder. But I knew that would only be the start. I was determined to let every American know about the misery in those windowless sheds in countless backyards across the nation, and in doing so I would try to change the laws. What was now considered acceptable would be exposed for the ugly truth that it is -- animal cruelty, deserving of punishment by every court in the land. I knew that taking on the dog-breeding industry would be no easy task, but I didn't care how tough the opposition might be or how great the cost or the sacrifice. I simply couldn't turn my back on those tortured animals.

Over the next year, I would see countless photos and video footage of puppy mills that were all staggering in their brutality and cruelty. My heart and spirit broke every time I saw documentation of the horrors of these breeding factories, where living beings were reduced to machines. Even my faith in God was shaken, not unlike many others who witness abuse day after day. But as many times as I felt despair, I refused to give up. Walking away simply wasn't an option when I thought of those who were unable to walk away.

That horrific and fateful trip to Texas was my crash course in puppy mills, and the desperate cries from those wooden sheds still haunt me to this day. When I returned to Chicago, I contacted my friend who had delivered the warnings about puppy mills weeks before. Now I hung on her every word. She directed me to local shelters, to rescue groups that specialize in certain breeds, and to Petfinder.com and 1-800-Save-a-Pet.com, national databases that match rescue dogs with potential adopters. On Petfinder.com I did a search for toy poodles and almost immediately spotted Baby's picture and bio. There she was, clinging to her foster mother, along with a sentence or two that described her as a puppy-mill survivor. That was all I needed to know.

Baby was rescued from a California puppy mill by a woman whom my friend Brian dubbed the "Drive-by Angel." One day, as she was driving, she saw a Puppies for Sale sign by the side of the road. For reasons she can't explain, she felt compelled to pull up to the house. The woman who answered the door wouldn't let her in when she inquired if there were any dogs available. She told her to wait outside.

Minutes later she returned with an armload of older, "spent" breeding dogs -- as mill owners call those who can no longer produce litters -- whom she deposited in an outdoor pen for Drive-by Angel to examine. One of the dogs repeatedly leaped in the air, trying to engage her, begging to be picked up. Her heart broke to see how underweight they all were, their coats filthy and matted. She knelt down to the skinny white dog who was so frantically trying to get her attention, who at that time only had a number, 94, not a name.

"They're too old to produce. I'm going to put them down," said the woman matter-of-factly. "You can have any of them for two hundred dollars." Drive-by Angel pleaded with the miller to reconsider killing perfectly healthy dogs, but the woman was unmoved. In the end, Drive-by Angel was able to take only one dog, number 94, whom her young children named Baby later that day. When I asked why they had chosen that name, she explained: "When I brought her home, everything was a first for her. Grass. Toys. Furniture. My kids said, 'She doesn't know about anything, just like a baby.' "

Drive-by Angel's life was full with work, kids, and other pets, and her thought was to keep Baby temporarily until a permanent home could be found. Just two days after bringing Baby home, as Drive-by Angel was leaving the house, Baby, in her eagerness not to be left behind, jumped off the sofa and shattered her left front leg. For a normal dog this wouldn't have posed a danger, but for a dog who had been deprived of exercise, proper nutrition, and who was overbred, osteoporosis occurs, thinning the bones to the point where even a simple jump off the sofa was too much for that little leg to take. The vet tried to set the leg three different times, but the bones were too thin and brittle to mend and he had no choice but to amputate.

After Baby's leg was removed, Drive-by Angel placed her with a woman I'll call "Sarah" who had fostered countless rescue dogs over the years and was no stranger to nursing homeless, damaged creatures back to health. She knew about the mill where Baby had come from, having seen other dogs come out of there with broken limbs and worse. It is common for small dogs at puppy mills to have their paws caught in the openings at the bottoms of the wire cages, wrenching their legs as they try to free themselves, which can cause fractures and breaks.

When she felt Baby was ready, Sarah posted Baby's picture and bio on Petfinder.com and waited, hoping for the best. Hundreds of miles away, sitting at my desk in Chicago, I was one of only two people who responded. I guess a three-legged puppy-mill survivor isn't high on many people's list for a pet. After reading my application, Sarah called and told me I was welcome to meet Baby in person.

Even though they were halfway across the country, I felt compelled to book a flight to California. Of all the Petfinder.com listings I read, hers was the one I couldn't forget. On some level that I wasn't conscious of at the time, I must have known there was a bigger purpose to my having found her listing, and that this little dog, who had been through so much, was meant to be with me. Once again I found myself in a rental car driving to another small town, located about an hour from the airport. When Sarah opened her front door, two small, white poodles were at her feet to greet me: Spunky and Baby, who was the smaller of the two. She hopped around the room on three legs, looking considerably happier than in her website picture. Clearly she was enjoying life with them. When I sat down, she jumped into my lap and made herself comfortable, as if she knew I was there for her. Other than the glaring absence of her front leg, the first thing I noticed was that she constantly -- and I mean constantly -- flicked the air with her tongue, a nervous tick she had likely developed after years of being confined in a cage.

Sarah filled me in on as many details as she knew about Baby's past. Inside her delicate pink ear I saw "94" tattooed, most likely the year of her birth. This would have been the breeder's method of checking her "expiration date," when she'd become too old to breed and would be killed.

As Baby looked up at me adoringly, it was hard to imagine the cold-heartedness of the breeder who was ready to snuff out this little angel, still so full of life. I considered the fate of the others that Drive-by Angel had left behind that day. As I gently held up Baby's ear flap to examine the tattoo, I thought of how many people get permanent body art, albeit voluntarily. Unlike an animal, they can brace themselves for the pain, understand the meaning of it, and accept it as something they are willing, even excited, to endure for the sake of the outcome. But for an animal, to be grabbed and tattooed without knowing what she has done to make someone hurt her so badly, why she is being punished, is altogether different.

Just as I thought Baby's story could not get any worse, Sarah told me that Baby couldn't bark because the breeders had cut her vocal cords so they wouldn't have to listen to the dogs' constant cries to be let out of their cages. This was later confirmed when I went to the breeder's home myself and she unashamedly boasted about sticking some kind of scissors down the dogs' throats to do the barbaric deed. Like the Texas puppy miller who dismissed the animals' suffering, she remarked, "It doesn't bother them." I held Baby close and looked at Sarah, wanting her to tell me what to do -- how to shut down these places. She just shook her head sadly.

As I listened, my anger mounted. I was resolved to do something, but, surprisingly, at the end of our meeting I felt torn about whether to take Baby with me. Much to Sarah's confusion, and my own, I flew back to Chicago without her. Despite the desperate plea in Baby's eyes, I knew I needed more time to summon my courage and prepare for this decision. As I look back, I think I was still grieving Blue's death and wasn't quite ready to allow another dog to come into my heart. Even more, though, I was scared. Would it be hard to take care of a three-legged dog? What about the fact that she was older? I had just lost a nine-year-old dog to cancer, and Baby was about the same age. And would her constant licking drive me nuts? I felt terrible even asking that; after all, it wasn't her fault that she had developed a nervous tick because she'd been abused. But I was still a novice at rescuing dogs and was afraid of the unknown.

Like a lot of people who have never rescued before, I thought of a rescue dog as "used" or having too much "baggage." I worried that no matter how much love, food, or care I gave her, she would never be able to overcome the trauma and pain of her previous life. I realize now that my fears had more to do with myself and my unresolved feelings about my own past than they did with Baby.

I sheepishly gave Sarah some excuse about why I needed more time and wrote her a check to cover expenses for Baby's care. I think she was dumbfounded that I had come all the way from Chicago to California and was going back without her, but she agreed to keep her awhile longer.

A couple of months passed and Sarah was, understandably, getting a bit impatient. She had travel plans and wanted to get Baby settled in the right home as soon as possible. If I didn't come and get her now she'd have to find another home for her or bring her to the shelter where she volunteered. That spurred me into action, and I booked the next flight out of Chicago. I had stalled long enough. This time when Sarah and Spunky greeted me at the door and that little lamb appeared beside them, looking up at me, I knew in an instant that she belonged with me.

"Come here, little mouse," I said, scooping her up (giving her the first of what would be 1,001 nicknames). As I pressed her to my cheek, I couldn't believeI had hesitated. All doubts had vanished. I knew in my heart that she was meant to be with me. I cuddled and kissed her during the entire drive to the airport, promising her a wonderful new life, vowing that no one would ever hurt her again. That night, after a room service feast at her first hotel, she slept pressed against my side. And after two days of round-the-clock loving, the nervous licking completely stopped.

The reactions Baby and I received were dramatic. Whenever I'd take her out for a walk we could scarcely make it down the street without people approaching us. They'd stop in their tracks or even slow their cars and roll down their windows to ask, "What happened to her?" "Is she okay now?" "Can I hold her?" "Where did you find her?" "I'm so glad she has you. That's one lucky dog."

I'd smile and tell themIwas the lucky one, that Baby was a precious gift. If I ever got tired of answering the same questions over and over, several times a day, I reminded myself that it was a small price to pay for spreading the word about puppy mills, and a golden opportunity to convince someone to rescue or adopt a dog instead of buying one from a pet store or breeder.

"Are the people in prison for what they did to her?" I was often asked. That was the hardest question for me to answer. I was as perplexed as everyone else as to why we don't have laws that protect animals from the kind of abuse that Baby and countless other dogs endure at puppy mills and backyard breeding facilities. Like the curious strangers who stopped us every day, I wanted to know why it wasn't a crime for people to lock animals in cages for years on end. And how could it be legal for an owner to cut a dog's vocal cords simply because he didn't want to listen to her cries to be let out of her cage? If these practices weren't recognized as crimes yet, I knew from the outrage of the people we were meeting that there was plenty of support to change the laws. Which is what I had made up my mind to do.

Even a talker like me eventually gets tired of repeating the same thing over and over, so I decided to have Baby's story printed on a card to give out to people. By then, I was more convinced than ever that I had to bring this issue to the country's attention, and I thought a good place to start would be to ask animal-loving celebrities and members of Congress to be photographed with Baby for a book. The yesses poured in, and before long, Baby and I were flying to Hollywood, New York, and Washington, D.C., in a whirlwind of photo shoots and meetings with some of our country's most beloved celebrities and influential leaders. Baby, of course, handled it all with her usual dignity, not knowing or caring who was a big shot and who wasn't. In our eyes, if someone promised to help stop animal cruelty, they were a superstar.

Sometimes in our travels and meetings we'd come across someone who didn't seem to care about speaking out against animal cruelty. That was hard for me. I'd get quiet for a long time, trying to understand how anyone could be unmoved by cruelty to animals. I knew that this kind of indifference was at the core of the problem and that only by addressing the reasons for such apathy would we ever hope to end this abuse.

"Not to worry, Baby," I'd finally say, more for my benefit, of course, than for hers. "There are more good people than bad. We will make a difference. I promise you."

I won't pretend that those experiences haven't taken their toll on me. Ask anyone who advocates for abused animals, and they will tell you that on top of having to absorb the horrific images and details of animal abuse -- the stuff of nightmares -- there's the added trauma of often being discounted or disbelieved by society, or even by certain members of one's own social circle. Those who are in denial about the abusive way society treats animals may range from one's relatives and friends to elected officials and the press. We may be alternately belittled, ridiculed, or altogether dismissed by certain segments of society that are not ready to hear or accept the truth about the ways we legally abuse animals. And that compounds the trauma for the animal advocate. Imagine witnessing a child being abused and then going to the press, to your elected officials, or to someone in your inner circle to tell them, and having them respond with indifference or even rejection. Other social justice advocates don't have to deal with the invalidation, rejection of facts, and outright denial by the public that animal advocates do, and as such, we may understandably suffer from depression, rage, and post-traumatic stress symptoms, not to mention despair over not being able to rescue the victims, whether from a puppy mill, factory farm, or other abusive industry. Taimie Bryant, professor of law at UCLA, has even written a paper, "Trauma, Law and Advocacy," on this phenomenon, and it was of some comfort to me to know that someone had identified and validated the compounded trauma that we often experience:

It is, therefore, not only the animals who suffer. An individual who knows the truth of this animal suffering and of society's failure to address it, is harmed by both the suffering and society's disregard. When that person shares her traumatic knowledge with another, his/her reaction can compound the truth-teller's pain. That person has seen something horrible, but when she tugs on someone's sleeve with the words, "This is awful, awful, awful," she is likely to be pitied for her frailty, chided for anthropomorphizing, or avoided for supposedly projecting her own traumas onto animals' experience.

People of all ages and backgrounds are drawn to Baby, asking to touch her and hold her. They want to love her. I can't tell you how many people have asked me if she's for sale. The first time somebody asked that, I clutched her tighter, appalled by the very idea. Now I'm used to it. She simply inspires that love.

Just the other day, Baby and I had an extraordinary encounter with a man on the street. He was bedraggled and obviously in trouble -- from his disheveled appearance and wild-eyed manner, I suspected he was probably in the throes of a psychotic or drug-induced episode, maybe both. He charged down the sidewalk toward us, screaming obscenities at the top of his lungs and ranting unintelligibly.

I stiffened as he got closer, wanting to pick up Baby and dash to the other side of street, but instead I froze, thinking of the schizophrenic patients I had worked with during my training to become a psychologist. I reminded myself that none of them had ever hurt me, that their enraged outbursts were more about their own terror of the world around them.

Having reached us, the man looked down at Baby on the sidewalk and abruptly halted.

"Oh!" he cried. "What happened to her?" His tone and face were suddenly transformed. He now looked and sounded completely lucid, like a totally different person than the one charging toward us moments before.

"She was abused and lost her leg," I said.

"Oh, no! That hurts my heart," he exclaimed, placing his hand over the spot on his chest.

I was so stunned I couldn't reply.

"You're taking good care of her, right?" he asked, looking at me squarely. "You aren't going to hurt her," he added more as a statement than a question.

I felt my throat tighten and my eyes well with tears for the empathy this troubled man was offering Baby, someone he identified with and wanted to protect, someone who, for that moment, inspired him to put aside his own agony and feel the pain of another. In the two years since I adopted her, I had never seen a clearer example of Baby's transformational power to elicit love, kindness, and empathy even in the face of one's own suffering. It is a power that animals singularly possess to heal the human soul.

"No one will ever hurt her again," I told him.

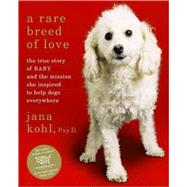

Excerpted from A Rare Breed of Love: The True Story of Baby and the Mission She Inspired to Help Dogs Everywhere by Jana Kohl

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.