What is included with this book?

| Overture | p. 1 |

| Coffin Notes | p. 4 |

| Muscadine Stains | p. 21 |

| I'll Fly Away | p. 34 |

| Behind the Doors | p. 49 |

| Inside the Mansion | p. 63 |

| Roadblock | p. 77 |

| Homeless | p. 94 |

| A Single Light | p. 103 |

| Sunrise | p. 117 |

| Shift | p. 127 |

| The Invisible World | p. 137 |

| No Time for Reflection | p. 146 |

| The Beginning of Disorder | p. 156 |

| A Long, Thin Limb | p. 172 |

| Mark's Horror | p. 183 |

| Scooting Chairs | p. 196 |

| Debacle | p. 211 |

| A Day Without Anvils | p. 226 |

| One Child | p. 245 |

| One Volunteer | p. 260 |

| The Secret Song | p. 275 |

| Arrival | p. 291 |

| Hope | p. 307 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 315 |

| About the Mercy and Sharing Foundation | p. 319 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter 1

Coffin Notes

IN THE WINTER OF 1995, I toured the pediatric and maternity wards of the government hospital in Port-au-Prince for the first time. Nearing the hospital, I could see dozens of women in the entryway, some clearly in advanced stages of pregnancy, others already holding tiny babies or toddlers against their breasts. A few were lying on straw mats or leaning against the concrete building, sweltering in the tropical heat. It seemed that each woman I passed either mumbled incoherently or wept, hands pressed to her face, her tears running between crooked callused knuckles. I had brought a few Haitiangourdesand American dollars to purchase water and medicine for the patients. I didn't yet know what else I could do.

An elderly gentleman dozed in the entryway with a shotgun balanced on his thighs. I gently tapped on the metal door frame beside him, and he started from his nap. Grasping his shotgun with one hand and the waistband of his britches with the other, he fumbled to keep his pants from falling down over his protruding hip bones.

"State your beezness," he said irritably, his English thickly accented with Creole.**Haiti has two official languages -- French and Creole (sometimes spelled Kreyòl). The majority of Haitians (about 90 percent) speak only Creole, a hybrid of French that includes some Spanish, African, and Taino dialects. English and Spanish are also spoken on a limited basis, particularly in the business community.

"She eez missionary." My companion, Viximar, a Haitian national, family man, and trusted friend, answered for me, although I disliked that description of myself and considered it inaccurate. I had come to Haiti without a Christian agenda or connection to an organization, only the desire to make good on a promise I made to God when I was little.

The elderly security guard waved us through. Once inside, I thumped Viximar on the arm.

"Don't lie!" I said.

He grinned. The wordmissionaryalways seemed to facilitate entry when needed.

If nothing else, I had come to Haiti hoping to leave my demons behind me, but soon after I arrived I realized that I had, in fact, fled to their native land. I had first come to this small country -- a mere five hundred miles south of Florida -- more than a year earlier, and in the twelve months that followed, I had witnessed more pain, suffering, and death than I could have possibly previously imagined. Though I had no earlier training or experience as a relief worker -- my last job was owner of an antique shop in Aspen, Colorado -- I somehow was able to start a small school and feeding program in Cité Soleil, a ravished district in the Haitian capital, arguably the worst slum in the Western Hemisphere. Viximar lived there with his family and was guardian of my school.

The hospital I was visiting with Viximar was the government hospital, and while it's not the only one in Haiti, it is the cheapest, and meant for the poorest of the poor. When Viximar and I went inside we found three large wards, each measuring around twenty by twenty feet. About a hundred children and infants lay in the three rooms. Most of them were covered with flies and ants, and though they must have ranged in age from a few months to several years, it was difficult to tell, given the distortions of illness and malnutrition. Some of the children appeared to be there alone; others had an adult holding vigil nearby; many of them were crying. But the ones who immediately caught and held my attention were the children who simply stared. They seemed oblivious to the swarms of flies and ants feasting on their excrement. They were alone with no adult to watch over them, their tiny faces sculpted only by bones, hunger, and fear.

Words penned by Elie Wiesel, Nobel Prize-winning journalist and Nazi-concentration-camp survivor, have haunted me since I first read them. Wiesel spoke of an old man who could no longer fight and would soon be a victim of the "selection." In the concentration camps during the Holocaust it was a frequently used term for those weakened and no longer able to perform labor. They wereselectedfor extermination. It was only now, as I looked into the eyes of these children, that the meaning truly penetrated my soul: "Suddenly his eyes would become blank, nothing but two open wounds, two pits of horror."

These children in the Haitian hospital had also been selected. For them it would only be a matter of time.

As I stood in the pediatric ward of the government hospital, I wanted to cry.No, I wanted to scream. But during the past year that I had worked in Haiti I had learned to do the opposite of what I would normally do back home in Aspen. So I stood there and thought through the situation: If I had been one of these children or mothers lying here, wondering if I was going to die, and I had seen a white woman, maybe for the first time, I would have been terrified. And if any woman would have looked at me and started crying, let alone screaming, I would have thought something horrible was happening to me.

So there was my answer. I wouldn't cry. I wouldn't turn away. I would do the opposite. Or something close to it, anyway: I would sing. And so I began to hum very lightly and smile at each person I passed, reaching out to touch tiny hands and feet.

I was afraid I would hurt the patients as I touched them; they had so many sores and bandages. I had never witnessed such agony. I wondered how many foreigners heard about this place and came, saw, cried, and left, never to forget it, yet leaving everything just as it was, as if they were never here at all. For several hours I walked through the maze of iron cribs and stained cots, in and out of the rooms, observing every kind of deformity, handicap, and disease that could be imagined.

I had spent the twenty years before I came to Haiti focused inward, on myself. My ambition had been to transform myself into someone who would be loved. Not satisfied with my natural state, I spent days at the hair salon and gym, manicuring, pedicuring, soaking, dyeing, running, tanning, waxing, and dieting. I read dozens of self-help books:Dianetics.Psycho-Cybernetics.The Road Less Traveled.Think and Grow Rich.Transcendental Meditation.The Celestine Prophecy.The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. From the moment I left my parents' home, at age fifteen, my sole purpose in life had been "self" improvement. I walked out the door with no money and only a tenth-grade education. But I knew a few things. I knew that the only way I would ever make it through my remaining seventy years -- what I figured I had left -- would be on my own. Not that I hadn't heard of God; I knew all about God. First, that He was slow. And second, that He seemed to have a mean streak, at least when it came to me.

Over the years, as part of my "self improvement," I had carefully buried my childhood memories, putting them safely in the ground, one by one, where I could keep track of them and keep them from contaminating my improved self. In the hospital in Haiti, as I walked on through each of the rooms, still singing quietly, I knew that for these children, growing up in this lonely place would result in the same sort of personal graveyard. If they ever got to grow up.

For years, I had scarcely touched a Bible, although I had gone to church every Sunday during my childhood in Alabama. I had spent most of each sermon watching the clock and hoping the preacher really meant it when he said "...and in conclusion..." for the seventh or eighth time. But the thousands of hours spent in a church pew had burned a complete set of hymns and Bible verses into my brain. Sometimes, when in trouble or depressed, I would hear the Psalms or other verses -- not as if they came from memory, but from an invisible presence between my shoulders. That presence returned to me while I was in the hospital ward, and I began to put words to my humming, quietly singing the comforting parts of hymns I remembered: "Oh Lord my God, when I in awesome wonder / consider all the works Thy hands have made..."

Through the rooms I sang, I hummed, I smiled, and I touched. So many sick people. So much despair.

INSIDE A RUSTED CRIB lay a bundle of rags with a skeletal face nestled inside. A woman, the mother, I assumed, leaned over the rail. She wept, seemingly inconsolable, and clutched a small square piece of paper. I avoided going near her when I first walked by because I didn't want to disturb her privacy and obvious grief. I later learned to recognize that reaction as a peculiarly American one.

With my tour nearly over, I was ready to leave the bundle of diapers we had brought for whoever needed them and go back to the hotel. I was finished with watching people suffer. But something inside me made me turn and walk back to the woman by the rusted crib. For a minute or so, I simply stood near her. I watched her as, through her tears, she followed the tiny spiral of her baby's rib cage, heaving up and down. The baby stared at the mother, sluggish but awake. As with so many of the other babies, ants scuttled around and within her badly dirtied diaper.

Gently, I laid my hand on the woman's shoulder. She lifted her head for a second and then collapsed under my touch. Viximar, who was at my side, rushed to catch her before she hit the floor. She was frail and gaunt, not more than eighty pounds. I asked Viximar to take some of my gourdes, buy water from one of the vendors on the street, and quickly get her something to eat, if he could find it. He helped me settle the woman near a wall beside the crib.

"Ti-Judith," the woman whispered, gazing weakly up to where her tiny daughter lay. That was the child's name: Ti-Judith.

I removed my fanny pack from around my waist and placed it under the mother's head so that her cheek did not rest on the filthy concrete floor. I returned to the baby, Ti-Judith, and peeled away the diaper that stuck between her teeny legs. It was laden with thick yellow liquid. I changed her diaper and cleaned her the best I could without water. The little girl's lips were cracked, and her long narrow feet and hands were skin-covered bones.

The mother had fallen asleep. I reached down and read the piece of paper she clutched between her bony fingers. She looked a hundred years old, though she couldn't have been more than twenty-five. The paper appeared to be a prescription, dated days earlier. I recognized the French word forsaline, barely legible, as the paper was soaked with either tears or sweat. The other word I recognized was an antibiotic.

When Viximar returned he knelt beside the mother and put a plastic pouch of water to her lips. She stirred, and almost immediately started to plead and cry again. I felt wetness forming in the corners of my own eyes but blinked it back. I thought of all the times that I made myself stop crying on demand when, with a stick in her hand, my mother said to "Dry it up!" After that, it was easier.

I tried to calm the mother, holding her hand, smoothing her hair, but she was crying for her daughter and wouldn't be consoled. I had never seen anyone bear another human being's pain with such desperate agony. I silently wished my mother had cherished me like that. I asked Viximar to try to get her to eat thegriot(fried goat meat) he had brought back in a grease-stained paper bag. The women initially refused, but after Viximar placed a bit in her hand, she put the small bite inside her mouth and chewed. A small glimmer awoke in her eyes. She reached out and gobbled up the meal with abandon.

While she ate I asked Viximar to tell me where we could buy the prescriptions on the piece of paper. The only doctor Viximar could find on the compound was an intern, but he confirmed that what was prescribed was in fact a saline solution and a common antibiotic. The intern did not know where to purchase the prescription at this late hour and went on to explain that to administer the medicine we would need to buy a syringe and some gauze, because the hospital did not have any left. I gave Viximar all the money I had in my fanny pack and instructed him not to come back until he found everything on the list.

While the mother dozed again, I picked up the baby girl and held her. She didn't cry at all. Her gaze seemed focused on something invisible in the distance between us. I lifted her to my lips and kissed her nose. She didn't look like a baby, really, except for her smallness. I wondered if she would ever smell like the babies I had held in the United States. I had always loved the smell of baby powder, baby lotion, baby shampoo, and baby clothes drenched in fabric softeners. Ti-Judith's little blanket was tattered and badly stained; the pink and yellow flowers on it were faded and barely visible. Her tiny fingernails were long and jagged. It seemed as if I were holding an incredibly old woman, wizened and decrepit. I wondered if this child would ever get to be any older than she was now. I took a deep breath and watched, staring at her until she closed her eyes, hesitantly, as if the greatest battle of her life was to stay awake.

When Viximar returned two hours later he had all of the items requested except the syringe, which could not be purchased until one of the official pharmacies opened the following morning. I asked Viximar to explain to the mother that we would be back tomorrow. He gave the woman the antibiotics, gauze, and five plastic pouches of saline solution. We stayed until she drifted into sleep again. I changed Ti-Judith's diaper once more, and asked Viximar to place the remaining part of the bundle of diapers under the woman's head. We left her in peace.

The mother didn't stir.

I SLEPT THAT NIGHT at the El Rancho Hotel in a small room with faded red carpet on the floor and a bright red clawfoot bathtub, in which I washed and rinsed my clothes for the next day. My room was near the hotel casino, a decaying 1970s remnant of one of the few periods when Haiti had rallied itself enough to lure a few cruise ships into its tropical ports. I turned the rickety air conditioner on high to drown out the noise below from the UN soldiers and their Haitian prostitutes, laughing and cheering from inside the casino.

My plan was to leave early in the morning, buy the syringes, and get to the hospital before the Port-au-Prince traffic became impenetrable. Thoroughfares in the Haitian capital are seldom dependable and usually jammed with rickety tap-taps (the colorfully painted passenger buses used by locals, notorious for their illmaintained brakes) or barricaded with burning tires planted by political activists or entrepreneurial protesters who will agitate against anything for a meal or a weapon or a few gourdes.

But when I awoke, it was to a pounding at the door and an angry sun beating through a gap in the partially drawn drapes. I looked at the clock on the nightstand -- 9:04 a.m. I had slept twelve hours. In an instant, I was completely awake. Racing around the room, I searched for my robe. "Hold on, I'm coming!" I eased the door open, leaving the chain intact.

"Madam, we must go! It is late!" Viximar said.

"My alarm must not have been set -- give me two minutes!" I said. Then, thinking more rationally, I took the chain off and opened the door. "Viximar, please go to the front desk and ask if there is a pharmacy nearby where you can get some syringes. By the time you get back, I'll be ready -- twenty minutes, tops!" Viximar nodded and then went running down the red-carpeted hallway.

Twenty minutes later I was ready, but it took us more than two hours to reach the hospital. Burning barricades manned by guntoting gangs made us turn back four times to seek other routes, but of course every other street had already been clogged by hundreds of other vehicles seeking to avoid the same obstacles. When we arrived it was already 11:30.

I went straight toward the back room and crib where Ti-Judith lay. Someone had attached an IV tube to her, but instead of embedding the IV into her forearm, someone had inserted the tube into a vein on the side of her head. The tube led to one of the plastic bags of saline solution we had bought the day before. Ti-Judith's face was less taut and seemed to be a shade darker than when I left her many hours ago. Her diaper, new when I had left her the day before, had not been changed since. I went about the business of wiping her red, irritated bottom and cleaning the plastic sheeting beneath her.

Where was her mother? Deciding that perhaps she had gone to relieve herself or was sleeping outside with the other women camped around the hospital's entrance, I picked Ti-Judith up, careful of her IV, and walked to an area of the building where everyone seemed to be resting. I sat down against the wall and propped the infant against my thighs with her head at the top of my knees. I took the small mirror from my fanny pack and held it closely in front of Ti-Judith's face. She seemed transfixed by her own eyes. I moved the mirror slightly to the right, then to the left. Her eyes followed. I couldn't think of any baby songs, so I sang "Jesus Loves Me," a song I had learned as a child. For the first time, I saw Ti-Judith smile.

We sat there for maybe fifteen minutes before Ti-Judith started to cry and strain a bit. I was afraid I had dislodged the IV, so I placed the bag on her belly and played with her lips with my finger. She poked a little pink tongue out, then pursed her lips. Her fingers wrapped around my forefinger, and she tried to force it into her mouth. I stood up with her and went in search of a doctor or nurse. I found someone who looked like a medic. In broken Creole I tried to tell him the baby was hungry and that I wanted to feed her. He just smiled.Okay. I surmised that since they had no gauze, no diapers, no syringes, no medicine, and hardly any doctors or nurses, they probably had no food. Cuddling the baby against my breast, I walked back to the crib assigned to her, in search of baby food.

Viximar was waiting near the crib. He was leaning with his head against the wall where we had left Ti-Judith's mother sleeping the night before.

"She ismorte," Viximar said, in a mix of Creole and English, looking at me with his head still against the wall. "She took the antibiotics, but they did not help her."

I stared at Viximar. It had not occurred to me that the antibiotics were for the mother.

"She had the bad blood," Viximar said. I looked at him, not understanding. "The AIDS; she had the AIDS." He shook his head sadly.

I looked down at the baby I held in my arms. I had put my finger in her mouth, not thinking that she also might have contracted the disease. She had sucked my finger and stopped crying.

"Who will take care of her now?" I asked, my voice wavering. "Where is her father?"

Viximar only shook his head. He did not know. We both looked at the baby in my arms.

THE TRAFFIC HAD ABATED somewhat, so it did not take long to reach the only market I knew of that sold Enfamil and baby bottles and return to the hospital. I spent the rest of the day holding Ti-Judith and talking to any doctor who made a rare appearance in the pediatric section. Around 6 p.m. I decided we should head back to the hotel before dark. There had been talk around the hospital that tonight in the downtown area there would be more shooting. I had learned not to second-guess this kind of gossip.

I changed Ti-Judith one more time, then left the Enfamil and a prepared bottle with a woman who was there with her twelve-yearold son, a burn victim. He had fallen into a kettle of hot oil that was used to fry griot and plantains. I gave her a few gourdes to buy the salve the doctor had told her to use to ease the child's pain, and she agreed to feed Ti-Judith a little of the formula every few hours until I returned the next morning.

After making arrangements to be picked up at 7 a.m. the next day, I gave Viximar a hug at the entrance of the hotel and said good night. Inside the lobby, a young woman with large inquisitive eyes sat behind the reception desk. "Madam Susie?" she asked. "I have a message." She handed it to me. It read, "Caller: Mr. Joe. Time: 8:53 p.m. Message: 'I love you.'" The woman smiled, revealing a large space between her bright white front teeth. "He said to make sure I tell you he loves you!" she said.

"That's my husband. I can't believe I missed him." I had tried to call him several times over the past few nights after returning to the hotel, but no luck. The phone lines worked sporadically, and when they did, all the hotel guests rushed to make calls, tying up the lines.

"Would you try to get a line out for me to make an international call?"

"Yes, I will try." And she did, each time pushing the receiver button down with her chubby forefinger. "The lines are down right now. We can try for you later."

I thanked her, went to my room, fell onto my bed, and prayed for the children at the hospital. I prayed they wouldn't suffer tonight, and that God would let them see their guardian angels so they wouldn't feel alone.

* * *

TI-JUDITH WAS DEAD.

Viximar and I stood behind a toothless man whose only clothes were a torn pair of boxer shorts and gray rubber fishing boots. As he pulled back a gigantic steel sliding door, I felt my head jerk back involuntarily and my eyes begin to sting. The stench that rushed out at us was so powerful it seemed to have texture. The man reached above the door and yanked a string to illuminate the room. I tucked my nose into the inside of my elbow and walked into what was surely the nearest place on earth to hell.

All around us were stacks of dead bodies, their limbs crumpled and askew. Blood seeped from the stacks, many of which towered above me, and all the corpses showed obvious signs of decay. Viximar took one look and then fled toward daylight and fresh air. From somewhere ahead of me came the unhurried exhalations of the morgue caretaker, who was somehow able to breathe normally. In my horror, I was only dimly aware of the sound, at least until I could no longer hear it.Where did he go? What if he closes the steel door and locks me in here?I was alone in the morgue behind the government hospital. I choked the thought from my mind and began to pray.Come back if You have left me, God! Oh, help me! You said you'd be with me always.My thoughts raced with doubt and fear.Ti-Judith. Oh, little girl. I must remember your face.I must concentrate on that.

My hands were clammy and I felt dizzy and faint. I realized I wasn't breathing. I took the hem of my dress and lifted it up to cover the lower half of my face. I took a breath. The floor sucked at my shoes -- I realized it was from blood that had drained from the corpses and not yet dried. It occurred to me that this was why the man wore rubber boots.

I turned around, and the man in his underwear appeared from the shadowy recesses of the room. He thrust a small naked male infant near my face. The child showed signs of having been dead for several days. I nearly gagged as I coughed and turned my head away.

"Is this it? He here long time!"

"No, no! A girl! Ti-Judith! She was brought here last night!"

The man flung the baby boy up onto the top shelf of the metal racks. He poked at my arm with a bloodstained finger and motioned for me to follow. I willed myself to move and then nearly fell as my shoe clung to the sticky blood on the floor.

I let go of the hem of my dress to use my hand to keep myself from falling onto the body of a young girl on the concrete in front of me. She was wearing only a torn pair of panties; on her face was the last grimace she had borne in life. As I reached up to steady myself, my hand brushed the bare belly of a woman tossed onto a concrete platform. She appeared to be at full term of her pregnancy. Her flesh was hard and cold. Between her colorless eyes was a small, blood-rimmed hole, about the size of a dime. Who would shoot a pregnant woman in the head? As I turned away I saw her gaping mouth move as if to speak. I started and began to run. I ran past the man in boots, the only other living creature in the room, and then over another body, that of a bullet-ridden boy. I was looking for Ti-Judith. I had to find her, I had to get her out of there. I tried to move quickly but the light was so dim; my eyes searched in vain through the remains of skinny children and tiny newborn babies that I discovered heaped in piles on the blood-covered concrete floor.

An eternity seemed to pass. I tried to hold my breath, and then grabbed a bunch of my hair and pressed it hard against my face. I reached for the rim of a gigantic wooden barrel to balance myself while trying to squeeze between it and a metal gurney that held the half-naked, decomposing body of what looked like a toothless old man. In front of me was a rusty metal rack of shelves that held several layers of deflated toddler-sized bodies. The sight of all the little feet hanging stiffly on top of the others tore at my heart.

Then I noticed for the first time the worms around the bodies. I gasped for air and smelled worm shit. The worms were writhing, slithering, feeding; they were shitting out what had once been mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, husbands, wives -- each of them the light and hope of someone's life.

I had to turn my face. For a split second, as I held on to the edge of the barrel, my gaze fell upon a line of wide, terror-filled eyes. I was sick and tasted vomit in my mouth.Oh, Ti-Judith, little girl. Where are you! Was I talking, thinking, screaming? I don't know.I will find you. I won't leave you here!As if in answer to my vow, I heard a scraping sound and, startled, turned to find the man with the boots and underwear holding a small limp body up by its right arm for my inspection.

"Is girl," the man said as he lifted her closer. Her open eyes had sunk deep into her head, and her tiny lips curled inward. It crossed my mind that she was not stiff yet. For some reason, this felt like an accomplishment -- she must have died only an hour or two ago. It was Ti-Judith. I nodded my head.

Outside, I knelt behind a rusted shell of an old car and cried and vomited. I wiped my face with my dress and rubbed my hands in the dirt. I walked slowly back and waited while the man wrote Ti-Judith's name down in an old ledger with a frayed and torn cover. The man handed me a broken pencil, and I signed my name on the line next to Ti-Judith's. I bought one of the tiny Styrofoam coffins that the man urged me to purchase, but I simply could not put Ti-Judith's body inside it. The coffin had no lining and seemed so uncomfortable for such a frail little girl. I cradled her tiny body in one arm, paid the five American dollars, grabbed the coffin under the other, and left.

Viximar and the driver had pulled up the truck near the entrance of the morgue. They were both silent as they opened the back of the truck and cleared enough space to place Ti-Judith's coffin and body. I shook my head and climbed into the front seat. I'd hold her, I told them. Viximar found a piece of plastic from a nearby pile of garbage and wrapped her in it. From their expressions, I could tell that her corpse had begun to smell. We drove to the orphanage towash and bury her.

There was no consolation in this moment, this tiny funeral procession for a dead Haitian child. There in the truck, my teeth were clamped together so tightly that I felt a bit of tooth break off. I spat it out and tilted my head back so far I heard my neck crack. I opened my mouth and began to scream. I screamed willfully, as loud as I was able. I didn't recognize the sound as my own. It was scratchy and high-pitched and agonizing. The sound of my voice terrified me as much as the fear of being locked in the morgue. I had completely lost it. Words spilled from me, and I ripped at my hair. There was no gauge by which I could measure reality any longer. Every face, every set of eyes, every pair of little feet was now part of me forever. I screamed again and again.

Ti-Judith lay wrapped in that torn piece of plastic on the seat beside me while I buried my face in my dress. She had died in the early morning while I fought off the usual monsters in my dreams. She was taken to that horrible place all alone. We found out later that the mother of the little burned boy had tried to rouse her to give her some of the formula, but she would not wake up. She had given the guard three gourdes to take the body to the morgue behind the hospital.

"Ummmmm, hmmm, uhummm, uhmmmmm." Inside the truck, Viximar began to hum a song he had learned from missionaries when he was a boy. He opened his mouth and began to sing

"Amazing Grace," quietly at first, then louder as the words came to him.

"Sing, Susie, sing for her," Viximar said. "Sing for Ti-Judith. In this world, she was loved."

That last phrase caught at my throat, a small comfort on the surface, but deep as a silver mine in truth. I wondered if Ti-Judith had ever known anybody who hadn't looked upon her as a burden. Ti-Judith's mother had loved her, I knew that. And I loved her. That was two. I imagined Ti-Judith in heaven, resting in the arms of Jesus. Her pain and suffering were over now. There would be no more hunger or tears where she was. Ti-Judith was indeed loved.

At the orphanage we cleaned Ti-Judith's body. We bought a used dress from a street vendor and put Ti-Judith in it. The dress was made for a little girl's party, pink with lacy trim and a white collar. It hung on Ti-Judith's tiny frame. We buried her in a small plot at the city cemetery. As the men lowered the coffin, I asked them to stop. Viximar ran to the truck and grabbed a scrap of paper, and with a pen from my purse I wrote a note.

On that note was a phrase I would write from that moment onward. I would write it repeatedly, and I would write it too often. I would write it in tribute to every child I ever knew who died. It was the phrase I wanted everyone who had ever been hungry, poor, alone, destitute, or sick to somehow know and feel and remember and hold close. Over time, the phrase would come to symbolize all that I held to be important.

The note read, "In this world, you were loved." I opened Ti-Judith's tiny coffin without a word, and slipped the note inside.

Copyright © 2007 by Susan Scott Krabacher

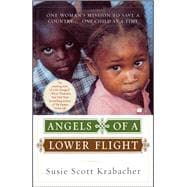

Excerpted from Angels of a Lower Flight: One Woman's Mission to Save a Country One Child at a Time by Susie Scott Krabacher

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.